Saturday Q&A

Has Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) been in the news recently? We seem to have gotten a lot of questions about him for some reason.

Q: Do we know Joe Manchin's position on D.C. becoming a state? It seems to me that

the obvious thing Democrats should be doing is making a filibuster exemption for new state votes, so they can add DC.

(Assuming they can get Senator Manchin on board with that. I would apply every available tool to convince him. We know

he's not likely to support any other filibuster reforms.)

With two new Democratic senators, it's a win for the party to then be able to change the filibuster and get to their

agenda, and a win for Manchin, who can then grandstand all he wants and vote with Republicans whenever he thinks he

needs to. Otherwise, nothing is going to get accomplished, or if something does get done, it will be so compromised to

please Republicans that it will only piss off the base. Either way, we've seen this dance before. Democrats then lose

big in 2022 and possibly 2024. (I would also bet that Senator Manchin is pissing off so many West Virginia Democrats

that they stay home on Election Day and send him packing. I know I would.)

Am I missing something? Why aren't Democrats prioritizing make D.C. a state over everything else? It seems to have

disappeared from the conversation.

S.S., West Hollywood, CA

A: As with so many of these issues, Manchin's position seems to change on a regular basis. Earlier this year, Manchin said he was open to statehood, not only for D.C., but also for Puerto Rico. More recently, he decreed that he would never vote for a statehood bill, and that if it is going to be done, it will have to be through a constitutional amendment. That's a pretty disingenuous position to take, since he knows full well a statehood amendment would never get the two-thirds vote it would need in each chamber of Congress, nor the support of three-quarters of the state legislatures. But is that his final position on the matter? Who knows? It would indeed free him to vote with the Republicans as he saw fit, but it would also mean he would have far less influence and would no longer be the center of attention. Perhaps he likes those things.

As to making a filibuster exception for statehood bills, Manchin has also said he's opposed to this kind of maneuvering. He probably suspects, and we think he would be right about this, that if you start carving out custom filibuster loopholes as needed, you start an arms race with the other party that leaves the filibuster fuller of holes than a block of swiss cheese, and no longer meaningful. If he becomes willing to revisit the filibuster, it will be in support of some sort of broad change: either converting it to a talking filibuster, or getting rid of it entirely.

Q: Now that Joe Manchin has made such a strong stand against both H.R. 1 and filibuster reform, the prospects for either of those things now seem bleak. For a long time, you seemed convinced that Manchin would eventually fold and support both of those things, and while I guess that's still possible, it looks considerably less likely now than it did last week. My question is, that given that Manchin's public pronouncements on the pursuit of bipartisanship have actually been pretty consistent, what made you think that Manchin would eventually get on board? And as someone who is a supporter of both voting and filibuster reform, what do you think are the chances of any movement in those areas in this current Congressional term? K.W., Sydney, NSW, Australia

A: There are two basic reasons we believe that Manchin will eventually come around, in some fashion. The first is that the incentives for him to get on board are enormous. If he's a loyal party man, this is the Democrats' chance to achieve some of their main priorities. If he's in it for West Virginia, this is his opportunity to score enough pork to keep Hormel in business for the next century. If he's in it for himself, he could have any committee chair he wants, or an eight-figure donation for his reelection PAC, or just about any other boon his heart desires.

The second reason is that Manchin's explanation for his intransigence is not especially believable. He has yet to say, for example, why he was ok with the For the People Act last term, but now he opposes it. More broadly, he has been in the United States Senate for more than a decade. He saw then-Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) steal a Supreme Court seat. He saw Trump skate on two impeachments. He saw the Joint 1/6 commission go down in flames. It is implausible that he thinks a new era of bipartisanship and kumbaya is just around the corner; he's too smart for that. It's almost as implausible that he believes bipartisanship is of such paramount importance that it's better for Congress to do nothing than to pass legislation supported by only one party.

As to voting and filibuster reform, they go hand in hand. H.R. 1 is a massive frankenbill, and was always going to face a tough road in the Senate. If it's broken into pieces, Manchin is going to have a hard time coming out against all of them, since he insists that he still supports some parts. Meanwhile, he's going to have a hard time sticking with the "bipartisanship is possible" when and if the Republicans vote down each bill. At that point, if there is anything that will change his mind, or will give him the necessary cover to change his position on the filibuster, then that will be it.

Q: Regarding Joe Manchin and what he's up to, is it possible that he believes that the Democrats will lose control of the Senate in 2022 and has made some kind of deal with Mitch McConnell to obstruct all Democratic legislation? Then in 2022, he switches parties and gets some plum committee assignment or pork for his district? Any other deals that make sense? A.R., Los Angeles, CA

A: Washington in general, and Manchin in particular, is always good for a surprise, so you never know. However, if Manchin is going to go rogue anyhow, we don't see what the point in waiting would be. Whether he wants to work with the Republicans or he wants to work with the Democrats, he will never, ever have more leverage than he has right now. He might plausibly deliver several major planks of the Democratic platform with an upturn of his thumb. Alternatively, he could instantly give McConnell his job back, and with that control of all committees to the GOP. If the Democrats extend their majority next term, or if they lose it, his leverage goes way down.

You might say: "What if Manchin turns traitor right now, and then McConnell betrays him next term and doesn't deliver the promised pork?" But that's an issue regardless. If there is a handshake deal, and then Republicans end up with a 52-48 advantage after the next election, McConnell could easily "forget" his promises to Manchin. If Manchin were to go public right now, he would, at very least, get to have his choice of committee chair for a year and a half, and would also have put the deal out there for everyone to see, making it considerably harder for McConnell to backslide.

Q: One of the primary arguments against eliminating the filibuster is that the Republicans will, one day, eventually regain control of the Senate. I, for one, feel we are at a point where the game has changed and evolved, and the Democrats are still playing an outdated version of politics (compromise, attempting to negotiate, coherent sentences, etc.). It is long overdue that they fight back. What is to stop them from eliminating the filibuster, and if in 2022 or 2024 the Republicans win a slight Senate majority, having a bill in their back pocket ready to go that reestablishes the filibuster before the new Senators are sworn in? S.M., Las Vegas, NV

A: Implicit in your plan is the notion that if the Republicans passed a bill killing the filibuster again, it would not work, because Joe Biden wouldn't sign it. However, the filibuster is not based in legislation, it's a product of Senate rules. And the president gets no say in Senate rules, only the senators do.

If the filibuster is killed, it will be the result of the Democrats raising a point of order objecting to a particular use of the filibuster, or to the filibuster as a whole. Points of order can be carried with a simple majority (51 votes) and are binding, so that would be enough to change the rules. If the Democrats changed things back as their majority was coming to a close, presumably by calling for another point of order, then the Republicans would just use their majority to call a third point of order, and would kill the filibuster yet again.

Q: Could the filibuster be challenged in court as unconstitutional? If so, by whom? Would a senator have standing to do so? As you have pointed out, the Constitution only requires a supermajority for a few specific and limited actions, which implies that all other legislation is intended to pass with a simple majority. If a filibuster prevents that, isn't it inherently unconstitutional? M.M., San Diego, CA

A: There have actually been attempts to mount a lawsuit like this, most recently in 2014, and they always run into several significant problems. The first, as you speculate, is the question of standing. It is somewhat difficult for an individual—whether a senator or not—or an organization to prove they have been harmed by the filibuster.

The second issue, which is even more significant, is that there isn't really anyone to sue. The filibuster is quite clearly the work of the 100 U.S. senators, but senators (like representatives and presidents) cannot be sued for things they do in the course of their official duties. The 2014 suit tried to get around that by suing Joe Biden (then the VP, and thus the president of the Senate), the Senate parliamentarian, the Secretary of the Senate, and the Sergeant-at-Arms of the Senate. The judge did not buy that, and tossed the suit.

The third issue, which is most significant, is that the filibuster, like other Senate (and House) procedures, is considered to be a political question, and thus not the purview of the courts (the formal term is "not justiciable").

Q: In the Senate chamber, the top chair is for the presiding officer, then there is a row for Senate staffers, and then another row in front of that. What is the function of the people in that first row? R.V., Pittsburgh, PA

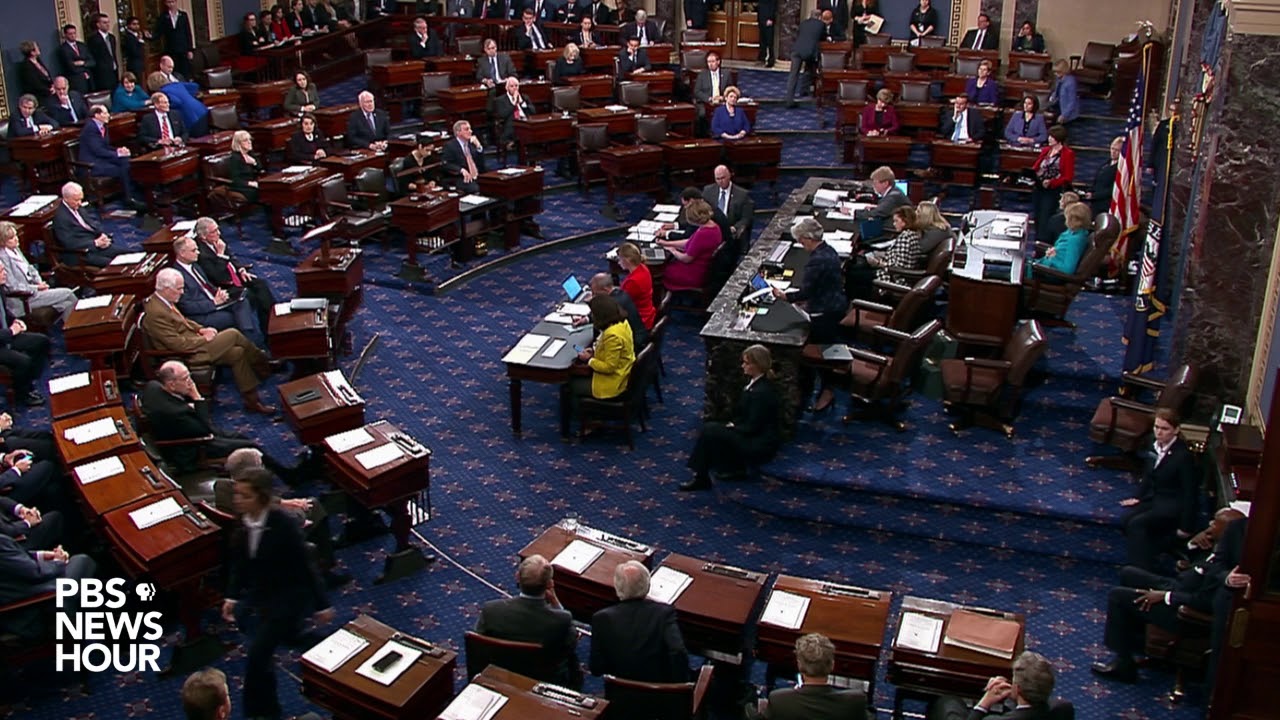

A: Just to refresh everyone, here is a picture of the front of the Senate chamber:

The presiding officer does indeed sit in the backmost row. In this picture, in case you are wondering, Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV) is presiding.

Meanwhile, on those occasions where the full contingent of Senate staffers is present (rarely are they all out there, and that includes this picture), the seats in front of, and flanking, the presiding officer are for: the Sergeant-at-Arms, the Secretary of the Senate, the Secretary to the Majority and Secretary to the Minority, the Journal Clerk (keeps minutes), the Senate Parliamentarian (or one of her assistants), the Legislative Clerk (reads and tracks the "ayes" and nays"), and the Assistant Secretary of the Senate or Assistant Legislative Clerk.

The front tables, meanwhile, are reserved for the use of the two parties, as they see fit. The one at stage left is for the Democrats, the one at stage right is for the Republicans. Usually, they seat experts on whatever legislation is before the Senate at those tables. During the impeachments, they had to put the small tables in storage and get out big, curved tables so they had enough room for all the people trying the impeachment.

Q: In a recent post, you discussed reasons the Republican Party would not split. Do you think it is possible that a group of 10 to 12 senators might decide to form their own party/caucus with the goal of negotiating in good faith? This group would have a lot of power and be able to get a lot of pork for their constituents and also be able to rein in some Democratic legislation. This would allow the new caucus to say things could have been worse if they were not involved, while also getting pet projects done. N.G., Millbury, MA

A: Isn't this basically a description of the "Gang of 10" Republicans?

The problem with a scheme like this is that the parties are so far apart that you can't find 10 Republicans able to stomach even a mild version of the Democrats' agenda. A handful, maybe, but not 10. And you can't find 10 Democrats able to stomach even a mild version of the Republicans' agenda. Again, a handful, maybe, but not 10.

There have been times in U.S. history where both parties had a liberal wing and a conservative wing, and this is what basically made reaching across the aisle possible. But now all the liberals are in one party and all the conservatives are in the other, and relatively few members are especially near to the center of the spectrum. That, plus the current emphasis on negative partisanship ("We are awesome, and the other party is pure evil!") is what makes bipartisan cooperation all but impossible in most cases. Certainly on any of the hot-button issues.

Q: Since the rise of Donald Trump, but especially since the events of January 6th, you have pointed out many times how the current radical wing of the GOP, centered around the 45th President and his legacy, is confronting a "moderate wing," highlighting the irony that this moderate wing used to be the ultra-conservative one at the turn of this century. That left me wondering: who were the "moderates" that battled for the control of the party when Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and George W. Bush were the ultras? What happened to them? S.C., Caracas, Venezuela

A: There are two reasons that a politician might be a moderate. The first is that "moderate" is that position that truly represents their views. The second is that they believe "moderate" is the most electable position, and so they occupy that position on the spectrum as a strategic matter.

Some of the "true" moderates of the early 2000s are still around, and are still trying to drag the Republican Party away from the fringes and toward the center of the spectrum. Sens. Mitt Romney (R-UT), Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), and Susan Collins (R-ME) would all be examples of this. Others have decided the Republican Party has no place for them, and have reregistered as independents or as members of some other political party. Former representatives Justin Amash (L), Joe Walsh (I), David Jolly (I), Wayne Gilchrest (D), and Joe Scarborough (I) are examples of this.

Meanwhile, the "opportunist" moderates of the early 2000s have largely determined which way the political winds are blowing, and have reinvented themselves as die-hard Trumpers. Probably the most famous example of this is Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC), but Marco Rubio (R-FL), Tim Scott (R-SC), and a whole bunch of representatives are in this group.

Q: Had Donald Trump not been president do you think he, his children or the Trump Organization would be facing prosecution for financial crimes? If the answer is no, does that give credence to the claim it is a witch hunt? C.L., Durham, England, UK

A: Let us start by pointing out that the incident that precipitated, at the very least, the investigation of Manhattan DA Cyrus Vance Jr. was an act committed in advancement of Trump's political concerns (the payments to Stormy Daniels and Karen McDougal). Without his political career, you don't have the precipitating act.

That said, it is probable that Trump and his family would have run afoul of the authorities sooner or later, and probably sooner. First of all, by all evidences, his business has been headed downhill for a while, due both to bad business decisions and to Trump's overleveraging himself. Second, he appears to have gotten away with a lot of chicanery over the past 10-15 years. Both of these things are likely to encourage someone to take larger, and more risky gambles, and so make it more likely that they will get caught with their hands in the cookie jar.

As to a witch hunt, recall that, by definition, the target of a witch hunt is innocent. Donald Trump does not appear to be. At very least, there is enough evidence of malfeasance that one cannot claim with a straight face that the accusations levied against him were created out of thin air (in contrast to the Salem "witches" in the original witch hunt, or the people railroaded by Joe McCarthy in the best-known metaphorical witch hunt).

Now, if you are asking "Has Donald Trump been singled out by the legal system?," the answer is probably "yes." But that does not make him a victim, nor does it give him cause to complain. There is a reason that people who drive red sports cars at 80 mph are more likely to get a speeding ticket than people who drive gray Hondas at 80 mph, and everyone knows what it is: the sports car driver is drawing attention to themselves. If you flout the law, and then build a highly visible public career in TV and other media (and eventually in politics) that is substantially built upon how skillfully you've flouted the law, you damn well better expect to be popped eventually.

Q: You

wrote:

"...Boebert's district, CO-03, is just R+6. Because of the way PVI is calculated, that means she only has a margin of

error of about 4 points."

Please explain that calculation and the apparent discrepancy between +6 and a margin of error of 4.

R.K., Highlands, NC

A: PVI compares congressional districts (or states) to the national average, and considers only votes cast for Republicans or Democrats. In 2016, Hillary Clinton got 51.1% of the two-party vote, which means Trump got 48.9%. In 2020, Joe Biden got 52.3%, which means Trump got 47.7%. That means that the Republican average, nationally, was 48.3%.

Meanwhile, in CO-03 in 2016, Trump got 56.5% of the two-party vote, and in 2020 he got 53%. That's an average of 54.7%. Comparing that to his national average of 48.3%, it means that CO-03 was 6.4 points more Republican than the nation as a whole. Cook rounds to the nearest whole number, so that gives us R+6.

Anyhow, because PVI's baseline is not 50%, but instead the Republican presidential average over the last two elections, and because Trump's average was a shade above 48%, that means that, on average, 54% of the vote went Republican (i.e., 48 + 6). So, Boebert has about a 4-point margin of error.

Q: Regarding your answer as to why the GOP doesn't expel Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), you said: "So, this 'punishment' would bother her not at all." Is it not possible to expel her from the party, as opposed to just the House Republican Conference, so that she can't actually run in the Republican primary? That's definitely a thing that's possible in many other countries, where joining a political party requires signing up and paying dues, as opposed to just ticking a box when registering to vote. If she couldn't run with an (R) next to her name, it would be very difficult to win in this two-party system, despite incumbency and notoriety. D.C., Brentwood, CA

A: As you point out, parties in Europe have membership requirements, including paying dues. If you don't meet the requirements, you're out. However, American political parties do not have such requirements. So, there's no clear standard for separating those who are "in" from those who are "out."

That's not to say it's impossible to expel someone from an American Party. The RNC has no provisions for it, but some state-level party organizations do. For example, in Utah, you can be tossed out of the party if, as a candidate, you fail to sign a statement committing yourself to the principles of the Republican Party. The Georgia Republican Party has no such rules, so they would have to add them if they wanted to toss Taylor Greene out.

However, such an exercise ultimately would be pointless. Yes, the Party can make a big show out of tossing you out on your ear, but they can't actually stop you from running in the primary as a member of the Party. And if you land the nomination, they can't stop you from being the Party's official candidate (even in states like Utah, that have expulsion rules). If they could, they surely would have booted the Neo-Nazi who landed the Republican nomination in IL-03 in 2018 (made possible because no other Republican opposed him).

Q: This past week, President Biden traveled to Europe for the G-7 summit, and then his big summit with Vladimir Putin. Meanwhile, VP Kamala Harris went to Central America to address the migration issues on the southern border. Is there a requirement for one of the two to be here in the United States while the other is out of the country? I'm thinking of what happened with John F. Kennedy's assassination in 1963, when both he and Lyndon Baines Johnson were in Dallas on that fateful day. R.H.D., Webster, NY

A: There are no "official" rules. There is an old bit of "trivia" that POTUS and VPOTUS are not legally allowed to fly on the same plane at the same time, for fear of it crashing or being shot down, but that's not actually true.

That said, everyone involved does try very hard to be prudent. So, while not strictly required, POTUS and VPOTUS do travel on different planes whenever practicable. As to international travel, the most common precaution taken is that the VP generally remains in the United States if there's a higher-than-usual possibility that he or she might need to take over, and to be in Washington on short notice. During the Versailles Conference, for example, VP Thomas R. Marshall (of "what this country needs is a really good five-cent cigar" fame) did not leave the U.S. in the event that something befell Woodrow Wilson while he was in France. Similarly, when Winston Churchill died, LBJ could not attend the funeral because he was bedridden with a severe respiratory infection. And in view of the possibility that his health might take a turn for the worse, VP Hubert H. Humphrey was asked to remain in the country as well and to skip the funeral. So, Chief Justice Earl Warren led the American delegation instead.

Q: While I agree it can be safely assumed, there actually is no requirement that a federal judge be an American (by any meaning) is there? J.L., Chicago, IL

A: Not directly, no, but indirectly there is. If you work for the federal government, and your duty location is in the U.S. itself, the law requires that you be a U.S. citizen, a person who owes allegiance to the U.S., or a person who is in the process of acquiring citizenship. Since there is no federal circuit for France or New Zealand, ipso facto, judges have to be American.

Q: I was dismayed to read your dismissive and bigoted comment to the effect that evangelical

Christians only support Israel because of a prejudice against Muslims. Can you quote any poll data to support this

contention? Have you yourself heard this directly from a substantial number of evangelical Christians? Can you present

any evidence whatsoever to support what you said?

When I hear right-wingers say that all Muslims support terrorists, I call it what it is: religious bigotry. And that's

exactly what your comment was.

J.B., Hutto, TX

A: First of all, what we said was that some evangelicals are motivated by anti-Islamic sentiment. We did not say that is the only reason, and we specifically noted that evangelicals' understanding of Biblical prophecy is another.

That said, (Z) has indeed been witness to Islamophobia from a great many evangelical Christians, having grown up among them. There is also ample polling data to support the assertion. Consider, for example, this poll from Pew. It finds that 41% of Americans in general think Islam encourages more violence than other faiths, while 63% of white evangelicals feel that way. 25% of Americans think that Muslims are anti-American, but 38% of white evangelicals feel that way. 44% of Americans think there is a natural conflict between Islam and democracy, but 72% of white evangelicals feel that way.

Q: You have been very balanced in regards to the 1619 Project. Although it may fall outside the purview of the site, I am curious of your thoughts on the University of North Carolina-Chapel-Hill's not offering tenure to Nikole Hannah-Jones. J.K., Short Hills, NJ

A: In academia, there are two basic types of job searches for tenure-track candidates. The first sort is called "closed" or "targeted," and is when a university (or a department) has a specific candidate in mind that they want to hire. The second sort is called "open," and is when the university invites applications from all interested parties. It is not unusual in an open search for 200-300 candidates to submit dossiers (cover letter, letters of recommendation, writing samples, etc.). At that point, the department that launched the open search goes through a lengthy process that is meant to appear meticulous and merit-based in order to winnow the pile down, usually to three finalists. While the process may identify some very good candidates, it is dubious that it very often identifies the three best.

Anyhow, ultimately you end up with one finalist or you end up with three. Either way, the candidate or candidates then usually visit campus and go through a two-day rigamarole that involves a teaching demonstration, and a talk based on their research, and a meeting with the dean(s), and a meeting with the grad students, and a tour of the housing options in the area, and a whole bunch of other stuff. The final item on the agenda is generally dinner with the faculty at a local, reasonably upscale restaurant.

And now, a story about an open job search that (Z) was privy to (not at his own institution, but at another). This search narrowed things down to the usual three candidates, who all came to campus for the usual two-day process, including the dinner at the end. The restaurant of choice for this particular department was a nice Italian place. The first candidate of three had been just fine throughout the whole process, and he ordered lasagna. After completing his meal—or, at least, the parts that could be eaten with fork and knife—he proceeded to pick up his plate and, in full view of his potential future colleagues, licked it clean.

The second candidate came to campus, and he was fine throughout the process, until dinner time. After some generic repartee, the department members who were at the dinner asked if the candidate had any questions they might answer. "Just one," he said. "Does the university have any rules against professors dating their students?" Oof. He might as well have worn a sign that said, "Sexual harassment lawsuit coming shortly."

That left just one finalist. He also made it through the two days without much problem, and he too made it through dinner, until question and answer time. In his case, his question was: "How are the Negroes on campus? Are they troublesome at all?" He was not speaking with irony. And this was in 1998, by the way, not 1958.

A few days after the third candidate had his visit and dinner, the hiring committee met to decide which candidate would receive their backing. "Well, folks," said the chair of the committee, "I guess we're hiring the plate-licker."

That is a 100% true story, and it illustrates that hiring decisions turn on strange things that are often not known, even to most members of the department hiring the person. (Z) has also been party to other job searches resolved in...interesting fashion. For example, there was a very close one where the professor who cast the deciding vote had lost his racquetball partner to retirement, and so voted for the only candidate who said they knew how to play racquetball. Or, there was another one where half the department loathed candidate A, and half loathed candidate B, and so they naturally hired candidate C, who excited nobody, but who was also loathed by nobody. By the way, each of the three case studies described here—plate-licker, racquetball player, and acceptable-to-everyone guy—still holds those jobs.

Hannah-Jones was a closed hire, but the same dynamic holds true: There are many reasons, possibly substantive, possibly trivial, why she might have been rejected. There are only a few people who really know what the truth is, and they are unlikely to explain themselves. She was approved by the department that wanted to hire her, but was rejected by the UNC Board of Trustees. It is unusual for the administrators to overrule the faculty in hiring decisions, but it does happen, and the administrators do have that authority.

There is a good argument for hiring Hannah-Jones. She is a prominent person who has won a Pulitzer and a MacArthur Genius grant, and so would bring attention to the university. She would likely diversify the faculty, both in terms of her heritage, but also in terms of her perspective. And she's reportedly got strong ties to the UNC campus and to the campus community.

There is also a good argument for not hiring Hannah-Jones. Her résumé includes one prominent item, namely the 1619 Project. That's a pretty thin basis for giving someone $180,000 a year, plus a position she basically can't be fired from, plus all the other privileges of tenure. What if she turns out to be a one-trick pony, and it's all downhill from here? Further, her signature project has come under legitimate criticism for its casual approach to evidence and for putting advocacy above fealty to the historical record. That's a problem in departments with rigorous evidentiary standards, which is most of them, including journalism, which is the one she would have joined at UNC.

And finally, there is a not-so-good argument for not hiring Hannah-Jones, namely that she irritated local conservatives and one or two prominent donors. If a university bows to that sort of pressure, and sends the message that its scholarship is subject to approval from these folks, then the whole faculty takes a hit.

Again, we do not know what exactly the issues were, since we weren't in the room for the department meeting where she was approved for tenure, or at the board meeting where she was denied. We can only identify what some of the issues might have been, while also noting that there may be things that nobody outside a handful of people at UNC is aware of.

Q: I note that many of your internal links to elaborate on items in stories are to Wikipedia and wonder how you would feel about your students using it as a resource? M.W., Northbrook, IL

A: First of all, students are going to use Wikipedia, whether we like it or not. And that's not actually a problem, in the sense that Wikipedia is no more or less likely to be accurate than a print encyclopedia.

The issue with Wikipedia is that students have to understand how to use it properly. First of all, they should have a good general sense of which articles are more likely to be accurate (basically, things that are high-traffic and so attract lots of eyeballs) and which are less likely to be accurate (basically, things that are political, or are somewhat obscure). They also need to understand how to follow the footnotes, and verify any strong factual assertion. That is to say, it's not necessary to confirm that Abraham Lincoln was born in Kentucky, but it is necessary to make sure that "there have been 12,000 books written about Lincoln" is backed with some evidence.

Finally, at least for a history class, students also need to understand that 95% of Wikipedia is secondary (or, really, tertiary) information. If you're writing an essay on Abraham Lincoln, you can use it for basic facts or for background, but largely you cannot use Wikipedia as evidence because, beyond an occasional quote or photograph that might be included, the information there was not created by Lincoln and his contemporaries. In other words, it's not primary evidence.

What (Z) does, in classes where this is likely to come up, is give a 10-minute talk on Wikipedia, what it is, and the right and wrong ways to use it.

Q: Has the United States fought in any "just wars," other than World War II? Even the Revolutionary War was supported by only about a third of the populace according to best guesstimates, right? And would World War II even have happened if the U.S. had stayed out of World War I? Where would the U.S. be today if it just did not fight in any of those wars? Would the world be better off or worse off? J.D., Menlo Park, CA

A: We should start by noting that, at the time these wars were fought, a sizable percentage of the U.S. population, and usually a majority, was convinced they were just. For example, the Mexican-American war is, to us, quite obviously a land grab. But to many folks in 1846, it was clear that Mexico could not hold onto all of its territory (true), and that if the United States didn't grab a big chunk of it someone else would have (also true), and that would have put the U.S. in a difficult position, national-security wise (probably true).

Point is, this is a question that necessarily implies a fair bit of presentist thinking. But even if we operate with the benefit of hindsight, and ideally more enlightened thinking, it appears to us that the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II all still qualify as "just." The U.S. was either trying to do something positive, or was acting out of a legitimate need to defend itself, or both, in all of these cases.

As to the world wars, they were an almost inevitable byproduct of one world order (kings and serfs) being replaced by another (democratic governments and manufacturing). It is improbable that either could have been avoided, regardless of the extent of the United States' participation. If France and the U.K. had won on their own in the west in World War I, they would have punished Germany, something we know because they did it even with U.S. involvement. And that would have set in motion the same sequence of events. If Germany had won in the west, they were pretty much bent on conquest, and would not have been too kind to the Brits and the French, so a similar dynamic would be expected, possibly with a second world war coming even earlier than 1939.

And while it is true that wars exact a terrible toll in terms of blood and treasure, they also tend to dramatically hasten scientific progress, cultural change, economic modernization, and other forms of growth. To take World War II as an example, it hastened the development of computers, made possible modern aviation, led to the unlocking of the secrets of the atom, propelled women's equality forward, led to some of the most successful social programs in the history of the planet (GI Bill in the U.S., NHS in the U.K., etc.), and pushed humanity forward in a bunch of other ways. We would not want to say "boy, the world is sure a better place because of that brutal and destructive world war," but we would say that the pros and the cons are both so great that the judgment you ask for is basically impossible to make.

Q: In last week's Q&A, while speculating on Trump replacing Woodrow Wilson, you implied that the Zimmermann Telegram's decoding and revelation made the US entry into World War I unavoidable. Is that really the case? Mexico (fearing another Veracruz maybe or simply being realistic) clearly rejected the proposal. Wouldn't the smarter U.S. move have been to firm up some diplomatic understandings with Mexico and to take some actions against Germany (sanctions, assets-freezing, etc.) short of the horrendous decision to enter the war? That decision, it seems to me, was far less forgivable than that of the European political and military idiots in August 1914, most of whom thought the war would be a 6-week quickie. By March 1917 the reality was well known. Could one stupid, unsuccessful diplomatic note have such an impact? I have to think it was something more, like securing the loans that the New York banks had floated the British. Can you elaborate on all this? (It's so much more pleasant to think about than the impending collapse of democracy in the USA.) D.A., Brooklyn, NY

A: By the time the United States entered World War I, there were a lot of arguments for war floating around. Some Americans were indeed concerned about the economic angle you point out. Others felt a humanitarian need to help friendly countries being devastated by war. Some said that if Germany won in Europe, they would be coming after the U.S. immediately thereafter.

The point is that by 1917, Americans had spent at least two years seriously acclimating to the notion of entering the war, and also two years of dealing with provocations from the Germans, most obviously the sinking of the Lusitania, but also unrestricted submarine warfare against American ships starting in February 1917. The Zimmermann Telegram was the final straw for many citizens, such that the generally dovish Wilson felt he could not possibly resist the public furor for entry into the war. The telegram was made public on March 1, and the declaration of war came on April 6. Clearly events were moving very rapidly, and we see no chance that a not-so-skilled politician like Donald Trump could have somehow changed their course. Heck, we see no chance that a very skilled politician like Franklin Delano Roosevelt or Ronald Reagan could have changed their course.

Finally, it is true that, by 1917, Americans knew full well how ugly the war was. By then, for example, Arthur Guy Empey's memoir Over The Top, which is recommended reading for any student of military history, had been a bestseller. However, Americans also took note that the populations and the treasuries of the warring powers had been badly drained by three years of a massive and brutal war. The U.S., on the other hand, was still fresh, and was in a position to literally overwhelm the Germans with men and materiel. Which is, in the end, exactly what the U.S. did.

Q: I know this question is pure speculation, but I just can't help but wonder how the 1968 Presidential election would have turned out if Robert F. Kennedy had not been assassinated during the primaries. Did he really have a chance to win the Democratic nomination? If so, were the chances good for him to win the presidential election against Nixon? M.D., San Tan Valley, AZ

A: RFK actually did not have much chance to win the nomination; he entered the race too late. After winning the California primary on the day he was assassinated (at a location, incidentally, about five miles from where Z is typing this), the delegate total was Hubert Humphrey 561, Kennedy 393, Eugene McCarthy 258. Humphrey's lead was close to insurmountable. The best-case scenario was a brokered convention, but LBJ would have been pulling the strings, and he loathed Bobby Kennedy.

If Kennedy had somehow gotten the nomination, he certainly could have won if he'd gotten a few breaks. However, he was probably a slightly weaker candidate overall than Humphrey and, of course, Humphrey lost. There was not as much polling back then as there is today, by a long shot. And there weren't too many polls, therefore, that compared Kennedy v. Nixon and Humphrey v. Nixon head-to-head. But there were a few. For example, the May 6, 1968, Harris poll had Humphrey leading Nixon 40%-38%, while Kennedy was trailing Nixon by that same spread. So, Humphrey was polling four points stronger than RFK in that one. To take another example, in the May 12, 1968 Gallup Poll, Nixon was up on Humphrey 39% to 36%, while Nixon was up on Kennedy 42% to 32%. So, Humphrey was polling 7 points stronger in that one.

We could also look at this in terms of the close states. Here are the six closest states that Nixon won, along with his margin of victory: Missouri (1.13%), New Jersey (2.13%), Ohio (2.28%), Alaska (2.64%), Illinois (2.92%), and California (3.08%). And here are the six closest states that Humphrey won, along with the margin of victory: Texas (1.27%), Maryland (1.64%), Washington (2.11%), Pennsylvania (3.57%), Connecticut (5.16%), and New York (5.46%). Kennedy would have needed to pick up about 80 EVs relative to Humphrey. Do you see a combo where he might plausibly have gotten them? He might have flipped California and New Jersey, but that was only 57 back then. It seems unlikely that he outpolls the Midwesterner Humphrey in Ohio, Missouri, or Illinois. And who knows about Alaska, but that's still only 3 more EVs. Meanwhile, there's every chance that Kennedy would have lost Texas, deepening the hole he needed to climb out of.

Q: I was happy to see your invite to send in alternate history questions, as I love pondering these sorts of issues. Here's one for you. How would the world be materially different today if dimpled chads and butterfly ballots (and the Supreme Court) had not prevented Al Gore from winning the 2000 election? O.Z.H., Dubai, UAE

A: Gore was not Bill Clinton or Barack Obama, and so would have been a competent leader, but not an inspiring one, nor one likely to achieve miracles in terms of bending Congress to his will. So, it's hard to predict that he would have secured universal health care, or even that he would have made all that much progress on global warming (an issue that, at that time, had not yet reached critical mass).

The one thing Gore probably would have done right is take Osama bin Laden and the relevant intelligence more seriously, since Gore was considerably more savvy to that threat thanks to his service under Clinton. That means that we're willing to speculate that 9/11 would not have happened. But, in a cruel twist of irony, that would also have sown the seeds of Gore's demise. He wouldn't have a "cause" to rally Americans around like Bush did, and he wouldn't have a list of policy achievements to run on, and he wouldn't inspire people. Meanwhile, the last time Americans gave the White House to the same party four times in a row was in the 1940s. So, Gore probably loses the election of 2004.

Who does Gore lose to? Maybe George Bush comes back for another go, though probably not, since he wasn't a great candidate and he had his chance. The second-place finisher in 2000, in terms of Republican delegates, was...John McCain. It seems fair to consider him the GOP nominee-in-waiting, since he was indeed the nominee when the party had an opening in 2008. So, we would guess that McCain gets the nomination and the win in 2004.

By that time, the Republican Party was very much in the thrall of neocons who were determined to have a war in the Middle East. In actual history, 9/11 became their excuse for it, but in the absence of 9/11, they surely would have come up with something else. McCain was both very hawkish (more so than George W. Bush) and very willing to accept influence from the far-right fringes of the Party. So, he likely would have gone for whatever war the neocons came up with, and the U.S. probably ends up at the same basic place it was by 2002 or so, just four years later.

If you wish to contact us, please use one of these addresses. For the first two, please include your initials and city.

- questions@electoral-vote.com For questions about politics, civics, history, etc. to be answered on a Saturday

- comments@electoral-vote.com For "letters to the editor" for possible publication on a Sunday

- corrections@electoral-vote.com To tell us about typos or factual errors we should fix

- items@electoral-vote.com For general suggestions, ideas, etc.

To download a poster about the site to hang up, please click here.

Email a link to a friend or share:

---The Votemaster and Zenger

Jun11 FBI Is Not Investigating Trump's Role in Insurrection

Jun11 Senate Confirms First-Ever Muslim Judge

Jun11 Omar Ruffles More Feathers

Jun11 Sinema, Boebert May Be Playing with Fire

Jun11 A Possible Answer to the Manchin Mystery

Jun11 Dumbest Member of Congress Unwisely Opens His Mouth

Jun11 California Democrats Move the Goalposts a Bit

Jun11 About Those Vaccine Incentives...

Jun10 Biden Goes to Europe

Jun10 Gang of 10 Wants to Do Infrastructure without Raising Taxes

Jun10 Democrats Can't Figure Out What Manchin Wants

Jun10 Transcript of McGahn Hearing Is Released

Jun10 Report: Police Did Not Clear Protesters for Trump's Photo-Op at Church

Jun10 The Primary Battle Has Begun

Jun10 Special Master Is Appointed to Vet Electronics Seized from Giuliani

Jun10 Val Demings Is Officially Running against Marco Rubio

Jun10 Keystone XL Pipeline, 2010-2021

Jun09 Senate Passes China Bill

Jun09 "Infrastructure, Act II" Has Commenced

Jun09 Senate Releases 1/6 Report

Jun09 Biden Judicial Nominee Confirmed

Jun09 McConnell Will Have His Say on 2022 Nominees

Jun09 Ladies and Gentlemen, Your 2021 Gubernatorial Candidates

Jun09 It's Not EVERY Republican Governor

Jun08 Deus Ex Manchin

Jun08 Unemployment Benefits Will Soon End in Many States (Most of Them Red)

Jun08 Obama Speaks Out

Jun08 Legal Blotter, Part I: Whose DoJ?

Jun08 Legal Blotter, Part II: Everybody's Talkin'

Jun08 Legal Blotter, Part III: Nice Try, Matt

Jun08 Legal Blotter, Part IV: No Mo Ducking Service

Jun07 Manchin Will Vote against H.R. 1

Jun07 Biden Rejects Latest GOP Offer

Jun07 McGahn Finally Testified

Jun07 Trump is Now Synonymous with "Cheap"

Jun07 Lara Trump Won't Run

Jun07 Republican Jumps into Senate Race against Warnock

Jun07 Kemp Survived

Jun07 NRA Drops Lawsuit against Letitia James

Jun07 Political Advertising Is All Wrong

Jun06 Sunday Mailbag

Jun05 Saturday Q&A

Jun04 What Is Going on with Donald Trump?

Jun04 What Is Going on with the DoJ?

Jun04 There Will Be No Presidential Commission on the Insurrection

Jun04 I Fought the Law, Part I: Louis DeJoy

Jun04 I Fought the Law, Part II: Matt Gaetz

Jun04 I Fought the Law, Part III: Mo Brooks

Jun04 Texas Backs Down, a Little