Previous | Next | Senate page

New polls: (None)

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Biden Will Focus on North Carolina

Joe Biden's team is greedily eyeing North Carolina, a state Barack Obama won in 2008 and Biden lost by only 1.4% in 2020. With a fresh abortion ban, steady population growth in urban and suburban areas, and a highly contentious gubernatorial race, they smell possible victory here. They believe that if Biden wins North Carolina's 16 electoral votes (as many as Georgia has and more than Arizona's 11 or Wisconsin's 10), no Republican has any plausible path to victory.

State Democrats want Biden to visit the state often and invest heavily in it. They think it is winnable. The governor, attorney general, and secretary of state are all Democrats, so Democrats can and do win statewide races.

North Carolina's Republican-dominated state legislature passed a ban on abortions after 12 weeks in May, overriding the veto of Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC) in the process. That guarantees that abortion will be a top issue in 2024. While not as strict as the bans in some other states, it is enough to energize Democrats and young voters generally.

Demographics are another key issue. The population was 9.3 million when Obama won in 2008. It will be 10.7 million in 2024. Much of that growth is due to migration from other states, especially to the Research Triangle area bounded by three big research universities: the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, North Carolina State in Raleigh, and Duke in Durham. There are also many start-ups around the Triangle and the people who work there tend to be college educated and probably skew Democratic. In addition, about 120,000 young people hit 18 every year in North Carolina. Since Obama's victory in 2008, that is almost 2 million new voters, separate from migration. In short, the potential Democratic voters are there. They just have to be registered and gotten to the polls.

Finally, the race to succeed the term-limited Cooper gives the Democrats hope. AG Josh Stein, a fairly generic Democrat, is running. The Democrats are hoping the Republican candidate is Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson. Then they could run against the Trump-Robinson duo, which means running against an extremely right-wing loony and also Donald Trump. Did all those new people come to North Carolina for that? However, if the Republican presidential nominee is a real Southerner, say, Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC), Nikki Haley, or Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL), then the Republicans will probably win the state. (V)

DeSantis' Super PAC is Launching a Bus Tour Through Iowa for the Candidate

By law, super PACs are not allowed to coordinate with the candidate they are supporting. They can hire ad makers and run television ads on their own, as long as they don't talk to the candidate about the ads. However, running ads doesn't work in Iowa, where the voters want to meet the candidate in person. So, Ron DeSantis' super PAC Never Back Down has chartered a bus to drive through Iowa. The organizers are crossing their fingers that DeSantis will see the bus by accident and decide to go for a ride on it, all without coordinating with him. It's quite the gamble.

DeSantis has an odd problem. His campaign is running out of money and he had to fire about 10 people. But his super PAC has over $100 million it can spend on ads, etc. But again, ads don't work in Iowa, hence the scheme for the super PAC to charter a bus and hope DeSantis accidentally stumbles upon it and gets in. It would be a pity if he missed the bus.

Apparently someone in the campaign or super PAC has noticed that DeSantis is rapidly sinking out of sight and they have to do something fast. In Iowa, that means retail campaigning, which he is not good at, although his wife is not bad at it. His team there said that they're not panicked by the state of DeSantis' campaign. That may or may not be true, since the latest poll puts Trump at 46% and DeSantis at 16% in Iowa. That's a 30-point gap. In addition, Scott is nipping at DeSantis' heels at 11%.

The bus schedule starts with: Leave Des Moines July 27 in the morning and get to Chariton at 12:30 for an event. Then a town hall in Osceola at 6:45 p.m., and on to Oskaloosa for meet-and-greet at 12:30 p.m. the next day. All of the events will be paid for by the super PAC, which is probably illegal. The super PAC has 21 full-time paid staff in Iowa and they have knocked on 200,000 doors so far. If the staffers are more user-friendly than the candidate, that might work. As long as they can keep the candidate away from the voters, the plan might be viable. In effect, the super PAC is running the campaign, which is definitely illegal if there is any coordination with the candidate. (V)

Congress Can Ameliorate the Electoral College Imbalance on Its Own

It has happened five times in the history of the country that the winner of the popular vote lost in the Electoral College. Two of the times were in the past quarter century. The last four times it happened (1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016), it was a Democrat winning the popular vote but losing the election, and the fifth time (1824) the victim was a guy who would become a Democrat shortly after the election (Andrew Jackson). Many Democrats have focused on abolishing the Electoral College, especially after Donald Trump arranged for false electors in some of the states he lost. The problem is, that would require 38 states to ratify a constitutional amendment, and that will never happen. Is it hopeless then? Danielle Allen has argued in The Washington Post that while the first-choice option is politically impossible, there is a second-choice option that the Democrats could carry out next time they get the trifecta: Enlarging the House.

The problem with the Electoral College is that low-population red states in the Midwest and West are greatly overweighted on account of their two senators. Wyoming has a population of 580,000 and California has a population of 39 million. In a fair system, California should have 67 times the clout of Wyoming. But in the Electoral College, the ratio is 54/3 or just 18. So Wyoming has about 3.7x more power than it really should have. The same holds more or less for Alaska, Idaho, Montana, the Dakotas, West Virginia, Hawaii and more states. If the smaller states were randomly blue or red, it might not matter, but except for Hawaii, all the other states with 3 or 4 electoral votes are red states, giving the Republicans more power than they would get in a system in which states got electoral votes based strictly on their population.

In 1790, each of the 105 House members represented 34,000 people. In the past, the size of the House was increased over time. That stopped in 1929 when Congress permanently fixed the size of the House at 435. The population then was 120 million, so each House member represented 275,000 people. Now each of the 435 House members represents, on average, about 760,000 people. If Congress wanted each member to represent 275,000 people, as in 1929, it could increase the size of the House to 1,200 members. In over 200 countries, the ratio of population to members of the lower house is less than 275,000. In Italy, it is 97,000. In Spain, it is 79,000. In France, it is 72,000. In the U.K. it is 45,000.

This expansion would also go far toward fixing the Electoral College problem. In a 1,200-seat House, California would have 142 House seats and 144 electoral votes, Wyoming would have 2 House seats and 4 electoral votes, and the ratio would be about 36. While not 67, it is more than 18, and would reduce the power of the small states. And the simple thing here is that all it takes to do this is for Congress to pass a new law. No constitutional amendment is needed.

A second problem with the U.S. electoral system is gerrymandering. If done right, the expansion could also address that. To make the math simpler, let's assume the House triples in size, to 1,305 members. But rather than make 1,305 smaller, gerrymandered districts, the number of districts is kept at 435 (or even made smaller). Each district would elect three members by proportional representation by party or ranked-choice voting. In that way, if a red district had one-third Democrats, they could elect one of the three members. It would be much harder for a partisan legislature to draw lines to grab nearly all the seats. Right now, if a Republican legislature draws a map with large numbers of 55% R, 45% D districts, the Republicans win all those seats. In a three-member district, each party would be assured of one seat and the other one would be competitive. The devil is in the details, but introducing multimember districts that were not winner-take-all, as is now the case, would go a long way to making sure the minority party in each district had a decent shot at some representation. A 1,200-member House and 240 five-member districts with some sort of proportional representation would make gerrymandering nearly impossible. The limit here is to have all House members run statewide and then allocate seats to the parties in proportion to the votes.

Having mixed representation per district might also reduce partisanship. If a single district had both Democratic and Republican representatives, they would have to work together to do things that benefit their district. In short, there are things that can be done by Congress to make democracy work better and which do not require a constitutional amendment. (V)

Republicans Have a College Problem

No, not the Electoral College. That is still working fine for them. It is regular colleges that are the problem. Consider Wisconsin, for example. Normally, the two big Democratic counties, Milwaukee and Dane (Madison), are balanced by the rural rest of the state. In April there was a race for state Supreme Court justice. Normally, April elections are low-turnout affairs. Something happened this year. Turnout in Dane, which holds the University of Wisconsin's main campus and the state capital, was higher than in any other county and also more lopsided for the Democrats. It was so big that it changed the state's math by overwhelming the Milwaukee suburbs, which are trending left anyway. If the turnout in Dane becomes the new normal, it will have a big impact on who gets Wisconsin's 10 electoral votes and all statewide races going forward.

Wisconsin is not alone. In 2000, Al Gore won Washtenaw County (Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan) by 24 points (60% to 36%) and 34,000 votes. In 2020, Joe Biden won it by almost 50 points (72% to 23%) and 101,000 votes. In college towns in Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Ohio, Texas, and Virginia, the same dynamic is playing out. Their counties were often reliably Democratic in the past, but they are producing landslides now and in some cases big enough landslides to overwhelm rural counties elsewhere in the state. Not all, but the trend is the wrong way for Republicans.

The effect extends even to smaller municipalities. The American Communities Project has produced a list of 171 small-to-medium college towns. Since 2000, 38 have flipped from red to blue and only seven have flipped from blue to red, and usually by smaller margins. Counties that went blue did so by an average of 16,253 votes, whereas counties that went red did so by an average of 4,063 votes. Also, two-thirds of the counties with college towns have grown more Democratic since 2000.

The ACP list of college towns doesn't include many large universities because they are in large cities and counties. But the effect is similar. Travis County, TX (Austin, where the University of Texas' main campus is), became 290,000 votes bluer in 2020 than in 2000. Hennepin County, MN (Minneapolis, where the University of Minnesota is), became 245,000 votes bluer in the same timeframe. Bernalillo County, NM (Albuquerque, where the University of New Mexico is), became 73,000 votes bluer.

North Carolina is a state that will be in the spotlight in 2024 (see above). There are nine counties there with college towns. Five of the nine have gone blue since 2000. Together the nine netted 12,000 votes for George W. Bush, who carried the state by 13 points. In 2020, Joe Biden netted 222,000 votes in those nine counties and Donald Trump carried the state by 1 point. For the Republicans, this is not a great trend.

College towns are becoming so important due to several factors. Some of the campuses have expanded, bringing in more left-leaning students and faculty members. Start-ups spawned by university research are also bringing in more people who lean Democratic. The quality of life there, from the arts scene to local craft beers, also tends to pull in more Democrats than Republicans.

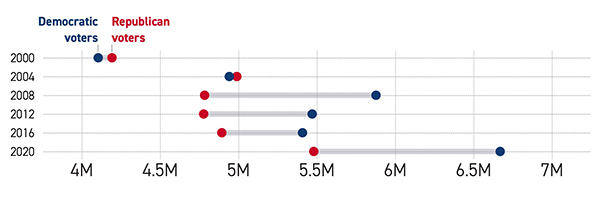

The chart below shows the combined votes of the counties where the 171 college towns are located:

This result is not entirely surprising, since both young voters and college-educated voters are swinging toward the Democrats. Naturally, the intersection of the two will swing even harder. This suggests that the Democrats should set up shop at the Universities of Arizona, Wisconsin, Georgia, and North Carolina, and make a big effort to engage students and faculty members. The potential payoff could be large.

Republicans could at least stop being so negative about higher education. Donald Trump recently wrote that he would "fire the radical left accreditors and hire new ones who will impose real standards on colleges." Those standards would include "removing all Marxist diversity, equity, and inclusion bureaucrats." Last month, Ron DeSantis sued the Biden administration over accrediting procedures. Students who receive federal aid must attend an accredited college or university. Among Republicans, only 19% have faith in higher education.

Traditionally, Republicans have viewed higher education as job training, so the metric for doing a good job is how much money graduates make. Democrats have tended to regard it as a place where students learn to think for themselves and criticize things they see as wrong. These views are not really compatible, and it is clear why college towns are hotbeds of anti-Republican politics and why the Republicans are unhappy about that. (V)

College-Educated Republicans Are Fleeing DeSantis

Let's continue the theme of Republicans and colleges a bit. Early this year, the backbone of Ron DeSantis' support was college-educated Republicans who hated Donald Trump. Three new Republican primary polls show that DeSantis' support among college-educated white GOP voters has been cut in half compared to the start of the year. A Morning Consult poll had him going from 41% to 23%. An Ipsos poll had him go from 39% to 20%. A Quinnipiac University poll had him at 51% in February and 29% now. This is a much larger drop-off than with other demographic groups. With three reputable pollsters saying the same thing, it probably is not a one-time statistical fluke.

None of the pollsters asked: "How come?" However, political operatives said that it was his hard-edged anti-woke-at-all-costs approach that was turning people off. Initially, college-educated Republicans were looking for an alternative to Trump and thought DeSantis might be their man. Then they discovered what he was like and were horrified. He might be able to recapture them, but that would require inventing a kinder, gentler, DeSantis v2.0, and that seems unlikely.

This development presents DeSantis with a real problem. Voters with no college are firmly in Trump's camp. If DeSantis can't win either college-educated voters or voters without a college education, who's left? Maybe college drop-outs? (V)

Green Party Wants to Blackmail the Democrats

Some people may be wondering why former Harvard professor Cornel West is running for the Green Party presidential nomination. Doesn't he realize that his run may result in Donald Trump, whom he hates with a passion, being elected president? Actually, he knows that very well and it is a feature, not a bug. West and everyone else running the Green Party know they have zero chance at winning a single electoral vote, let alone 270 of them. That isn't the point or the goal. The goal is essentially to blackmail the Democrats. If they don't adopt the Green Party's views on climate change, social justice, and other issues, the Greens will run West, and the Democrats' chances will go south, giving them the blues. Translated into Mafia-speak this is: "Nice candidate you got there. It would be a pity if he lost."

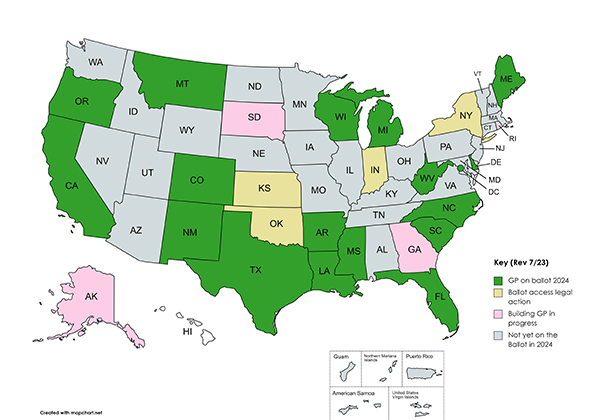

The Green party has about 200,000 registered members and 133 of them hold public office, mostly at the local level, like city council members. The reason West is seeking the Green Party nomination is that it is on the ballot in 17 states and D.C. and fighting for access in many more. Here is a map showing where it is on the ballot so far:

Most states don't matter. If the Green Party gets even 5% of the vote in California, it won't flip the state. But it is on the ballot in Wisconsin, Michigan, and North Carolina, where siphoning off even 2% from Biden could result in a Trump victory. This puts the Democrats in a bind. If they move to the left, then they can neutralize the Green Party, but lose votes to No Labels if it gets on the ballot in many states. If they move to the center, they may neutralize No Labels but lose more votes to the Green Party. Joe Biden has been around the track a couple of times so he understands the problem, but he also knows there is no easy solution (other than to try to block both No Labels and the Green Party from getting on the ballot in as many states as possible).

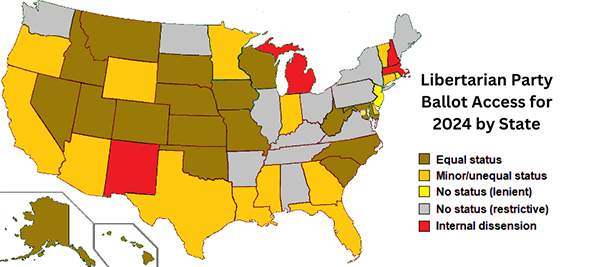

In principle, the Republicans have the same problem. They could bleed votes to the Libertarian Party on the right and to No Labels on their left. Here is the ballot access map for the LP:

But the situation is not symmetric. Many Trump supporters would walk over broken glass barefoot to vote for Trump. They won't defect. Biden's supporters like him and think he is a decent person, but some will be lured by the Green Party's siren song. Unless somebody lashes them to the mast, they could give in. Also, the Libertarian Party is not really trying to blackmail the Republicans. They have their principles, stand up for them, and let the chips fall where they may. Both maps are in flux as both parties are trying for a 50-state strategy. Again, it is ballot access in swing states that matters, not in solid states. (V)

No Labels Missed Its Chance to Be a Bold New Independent Voice

The No Labels platform is cold pablum. It just takes what the Democrats want on each issue, what the Republicans want on the issue, adds them up, and divides by two. This is mealy-mouth centrism at its worst. It's been tried and doesn't work. Matt Bai has a very different suggestion: Don't average each platform to the mushy middle, but take bold steps that make sense, some from the Democrats and some from the Republicans. For example, propose that the Second Amendment applies only to well-regulated militias (which is what the Constitution actually says), making the Democrats happy. But also propose greatly reducing government spending by means testing all government programs (which makes Republicans happy). Or, they could support fighting climate change (which is a threat to the planet and would make Democrats happy) while also supporting free speech, even if it made some people feel bad and maybe even cry (which would make Republicans happy). We point out that good libraries have a balanced collection of books, many of which take strong and different positions. They don't stock only individual books that are balanced.

Bai's point is that an independent movement that wants to rejuvenate democracy can't do it by seeking the mushy middle and avoiding new ideas. It can be centrist and bold at the same time, by taking key ideas from left and right. Donald Trump didn't take over the Republican Party by averaging out the ideas of Jeb! and Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL). He struck out in a completely new direction and Republican voters ate it up. An independent movement could do that as well. This could even be a blueprint for a party that could replace the Republican Party when Trump has exited stage right. After all, things change in politics. In Abraham Lincoln's time, the Republicans were a left-wing anti-slavery party, while the Democrats were the conservatives. Before the GOP came along, the Whigs tried to play both sides of the street for several years. It didn't work so well for them. (V)

Both Parties Introduce Election Bills

Both parties (naturally) have a keen interest in voting, but their approaches to it are quite different. The Republicans' bill, the "American Confidence in Elections Act," was introduced last week. It would urge states to adopt photo ID laws, would override some voting laws in D.C. (which Congress controls), and would ban the federal government from using political donor rolls. It is opposed by a coalition of 45 groups that want to protect voting rights, including ACLU, NAACP, SEIU, Brennan Center for Justice, NEA, and Verified Voting, among others. They note that the bill is not about confidence, but about voter suppression in many forms. Just as one example, Joe Biden has issued an executive order directing federal agencies to help people register to vote. This means that when potential voters have contact with various agencies, they will be encouraged to register and given help to do so. The Republicans' bill would cancel the XO.

Now the Democrats have introduced their bill, the "Freedom to Vote Act." It would expand voting access, reduce the influence of dark money, end gerrymandering, and safeguard the electoral process. Among other things, the bill:

- Requires early voting for at least 10 hours a day for at least 2 weeks prior to any election

- Allows no-excuse mail-in voting for any voter who asked for it; prevents ballots being rejected for minor reasons

- Makes sure individuals with disabilities have an opportunity to vote despite their disabilities

- Requires states that have an ID requirement to allow a wide variety of ID forms as well as alternative options

- Allows automatic registration when eligible voters have contact with a government agency unless they opt out

- Requires states to have same-day registration on Election Day

- Allows online voter registration in all states, something many states already allow

- Prevents unlawful voter purges

- Makes it a federal crime to trick voters about voting (e.g., no more "Voting is on Wednesday this year" stickers)

- Establishes a clear procedure for former felons to be reenfranchised

- Requires states to make sure that no voter has to stand in line more than 30 minutes to vote.

- Gives voters the right to sue if their right to vote has been violated

- Prohibits politicized removal of election officials

- Bans partisan gerrymandering

- Makes it easier for citizens to challenge district maps

- Requires any group that spends at least $10,000 in an election to publish the names of its major donors

- Improves enforcement of campaign laws

- Allows states to opt in for small donor matching for House elections

- Improves election security in many ways

If you are thinking, this sounds a lot like the old H.R. 1, you are right. It does. H.R. 1 passed the House in 2017, but was killed in the Senate. Democrats also plan to reintroduce H.R. 4 soon as well. It would patch up what is left of the Voting Rights Act after the Supreme Court took an ax to it.

The Democratic and Republican bills are almost diametrically opposed. There is no chance anyone from either party will vote for the other party's bill, so both are dead on arrival. The only way for either bill to pass would be for one party to get the trifecta and then abolish the Senate filibuster. (V)

Murkowski Would Support Manchin

Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) said that in a race between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, she would vote for Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), who is a potential candidate for the No Labels Party. Of course, Manchin hasn't said that he will run on the No Labels ticket, assuming they actually launch a full-blown party and campaign. Still, it is rare for a sitting senator to openly support someone from the other party, even if that person is running on a centrist ticket. She also said that she doesn't want to vote for the lesser of two evils. She wants to be proactive and support someone she thinks would be a good president. She thinks Manchin fits the bill.

Murkowski also said that some of her constituents have asked her to try to talk Manchin into running for president. She rebuffed them by saying: "That's not for me to do." But she is intrigued by the idea of a third party. Separate from that, it is also true that Murkowski and Manchin are close personal friends, possibly the only cross-party friendship in the Senate that is genuine. They have also each endorsed the other one in their respective reelection races, a rarity in the modern super-polarized Senate.

When a reporter asked Murkowski about the possibility of a vote for Manchin being a vote for Trump (whom she detests), she backed off a little and said she would have to think about it then. For Murkowski, crunch time comes if it is Biden vs. Trump and Manchin just runs for reelection. Sure, she can endorse him for reelection, but does she skip the top race on the Alaska ballot, leave it blank, and just vote for the House seat and lower down? (V)

Is There a Way to Keep AI from Causing Great Damage?

Last week we ran a series of 20 images and asked readers to determine which were real. The conclusion from analyzing the responses is that the fakes fooled people 38% of the time, even though everyone was told in advance that some of the images were fake. The consequences of being able to make fake images that look realistic and fool many people are enormous and could sway the 2024 election. Imagine a realistic photo of Joe Biden or Donald Trump on a stretcher being put into an ambulance with the caption: "Trump/Biden had a heart attack." A lot of people would believe the photo, no matter how many times it was denied later on. Many people would say: "You can't fool me. I saw the photo of it." Actually, you can fool them. Is there anything that can be done about this before it is too late?

Biden got Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and three other big players in the AI business to agree to some voluntary safeguards to try to make the problem less bad. One of the safeguards is to let other tech companies check out their software products before they are released. Exactly who would do the checking wasn't specified. Theoretically, the software would also be vetted for racial and gender bias. Another safeguard is some kind of watermarking that would allow people to determine if an image is fake. Of course, if the watermark is invisible and you have to feed the test image into some piece of software to get an answer, that is hardly worth much. A rule like: "Every AI-generated image must have a label 'This image was generated by a computer. It is not real.' in 12-point Helvetica bold in red on a white background in the lower right-hand corner of the image" would be a fine start, but that wasn't what was agreed to. Similarly, it would be nice if the byline on AI-generated texts was "This article was generated by a computer," but that wasn't in there either.

Whether a voluntary scheme like this can succeed remains to be seen, especially since making it easy for people to distinguish fakes from the real McCoy defeats the purpose of generating the fake in the first place. Companies want people to believe the fakes. That's why they made them in the first place. We doubt that this scheme will provide much protection and will probably soon fall apart.

Congress could step up and mandate such visible disclosures. Some companies would no doubt scream "FIRST AMENDMENT," but Congress has passed laws about other kinds of disclosures and they have held up in court. Products made in China have to be labeled "Made in China," even if the manufacturer would prefer not to. Most packaged foods have to list their ingredients, usually in the order from the largest amount on down. If the top two ingredients are water and sugar, they have to list them, like it or not. Packages of cigarettes have to have a warning that smoking isn't so good for you. The power of Congress to force companies to label their products is well established.

A completely different approach is to rely on tort law. If you have a swimming pool in your unfenced back yard and a local child falls into it and drowns, it's your fault. You should have had a big fence around your yard. Similarly, if a depressed teenager asks a chatbot for the three best ways to commit suicide and it suggests eating rat poison, shooting yourself, and jumping out of a 10th story window as three good options, the maker of the chatbot could be held liable. The possibility of being sued could well cause the makers of AI software to be careful. This is no doubt the reason that Adobe blocks many kinds of images, as we mentioned last week.

The problem with relying on tort law is proving that the chatbot's advice was the reason the teenager did it and absent the advice wouldn't have. Also, sometimes the damage is indirect, such as AI generating disinformation about elections and candidates. Probably relying only on the threat of lawsuits to keep AI companies honest isn't going to work all by itself, but it could also have some value in addition to legal regulation. (V)

Previous | Next

Main page for smartphones

Main page for tablets and computers