Previous | Next | Senate page

New polls: UT

Dem pickups: AZ FL GA MI NC PA WI

GOP pickups: (None)

Trump Had a Busy Day on Friday

Whether it is due to the pressures of COVID-19, or fear of losing to Joe Biden, or not enough golfing, or some other reason, Donald Trump is certainly...active these days. He made all sorts of news on Friday, and not of the positive sort.

Let's start with the thing that's getting the most attention. You'll be shocked to learn that it's...a tweet. Here it is:

That got quite a bit of blowback. Eventually he decided to "clarify" it:

Looting leads to shooting, and that’s why a man was shot and killed in Minneapolis on Wednesday night - or look at what just happened in Louisville with 7 people shot. I don’t want this to happen, and that’s what the expression put out last night means....

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 29, 2020

The historical context of these tweets is being discussed all over the place, so maybe you've heard it. In case you haven't however, the "when the looting starts" bit comes from former Miami police Chief Walter Headley. A segregationist, he said it in 1967, and was communicating his disapproval of left-wing activists, particularly black left-wing activists. Headley earned a lot of attention the next year due to the...vigor with which he and his men maintained "order" during the 1968 Republican National Convention.

Anyhow, Trump has presumably never heard of Headley, though it's probable that whoever shared the phrase with the President has. Still, the fact that he responded to such a tense situation with threats of violence is instructive. He did not respond to Charlottesville in that way, for example. Also instructive is the use of the word "thugs," which is almost universally a barely encoded dog whistle that means "black thugs." In other words, of course the tweet is racist, and no amount of spin will change that.

If that was not enough, as you can see, Twitter decided once again to implement its new policy of labeling Trump tweets. This time, the label is actually a bit stronger than it was in the previous two cases. Not only does this one accuse the President of encouraging violence, it also causes the Tweet to be hidden unless people specifically click on it, and it prohibits people from commenting on the tweet, liking it, or retweeting it. In short: We'll show you an executive order. Trump has yet to express his pique over the decision, maybe that will come today, or maybe he will wilt.

That was not all for the day, though. Continuing the search for a COVID-19 scapegoat, the President executed the rare double-scape yesterday, announcing two different buck-passing initiatives. First, he said the United States is cutting ties with WHO, as the whole COVID-19 situation is their fault. Whether he has the authority to make that decision unilaterally is an excellent question. Whether turning your back on the world's leading public health authority in the midst of a global pandemic is an even better question. Assuming Trump pulls it off, the next president is just going to restore the relationship, so this could prove to be a very short-term decision, indeed.

Shortly after the WHO announcement, Trump made a second declaration, this one aimed in China's direction. Rattling off a lengthy list of offenses, many of them legitimate, some less so, the President said he is going to slap sanctions on trade with Hong Kong. That actually makes sense, since they're just a client of China now. However, it's going to trigger retaliation from the Chinese, and so the Sino-American relationship is headed to yet another new low.

Those are the major Friday developments; time to brace yourself for whatever today will bring. Probably best to wear a helmet. (Z)

Saturday Q&A

This is a long one; there were a couple of recent items that generated a lot of questions, most obviously the attempt to classify all the presidents along today's political spectrum.

Q: Should the Democrats win back the Senate majority in 2020, could new Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) bring up for debate/vote any of the 400+ bills passed by the House under Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) in 2019-20 and blocked by current Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY)? Or would the House have to pass these bills again for this to happen? S.M., Trenton, NJ

A: He would be able to bring up, debate, and vote upon any of the bills that he wished. However, they would still have to be re-approved by the House, since all legislation expires at the end of a Congressional term.

Naturally, if a Pelosi-led House passed a bill one time, it would likely be happy to pass that same bill again. And the House would definitely remain under Democratic control in this scenario, as there is no way the Democrats win the Senate but lose the House.

Q: For the sake of this hypothetical, let's say that Joe Biden wins the presidency in November and the Democrats keep the house and grab the Senate 51-49. Now let's say that Chuck Schumer finally puts the filibuster out of our misery, and we've got a simple-majority Senate for the first time in 184 years. With the GOP having just stacked the Federal bench with so many lifetime-appointed, young conservative judges, could the Democrats vote to expand the amount of judges in each district and load up all of those newly created vacancies with young liberal judges in a do-unto-others-as-they-have-done-to-you, tit-for-tat attempt to restore a fair judicial balance? J.L., Los Angeles, CA

A: Absolutely. The very first sentence of Article III of the Constitution, the portion that outlines the structure of the judiciary, reads: "The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." Consequently, the maneuver you propose would have a rock-solid constitutional basis.

Q: Regarding Stan Greenberg's VP polling that you cite in "The Veepstakes, Part I: Key Democratic Pollster Pushes for Warren," I'm curious: Which version of Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) is he talking about? The one who was rock-solid behind Sen. Bernie Sanders' (I-VT) Medicare-For-All? Or the one suggested that the latter was an end goal that we needed to move gradually toward? Or the one who says that we just need the public option added to Obamacare? Each one of these Warrens has the given name "Elizabeth"; do you know which Warren Greenberg is advocating? D.A., Brooklyn, NY

A: Yes, as we've written, Warren is a bit of a chameleon. All politicians are, of course, it's just that she's a little more obvious about it.

With that said, there's clearly a role that Greenberg sees her occupying. She can't be at odds with the presidential candidate. Biden is all-in on expanding Obamacare, since he's a moderate and a big part of his pitch is "I'm Obama v2.0." So, Warren has to be on board with that. However, she can spend the entire campaign railing against banks, and privilege, and how the little guy is getting screwed. This is the dimension of progressivism she's always cared most about, and the dimension she's done the most work on (see, for example, her efforts related to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which predate her political career). She would certainly have credibility in this area with a lot of voters.

Q: On several occasions, you've mentioned that, based on their Senate voting records, Elizabeth Warren was actually more liberal than Bernie Sanders. I imagine you must have done an item and referred to an article on this subject before the primaries, but I must have missed it and can't find it. D.L., Paris, France

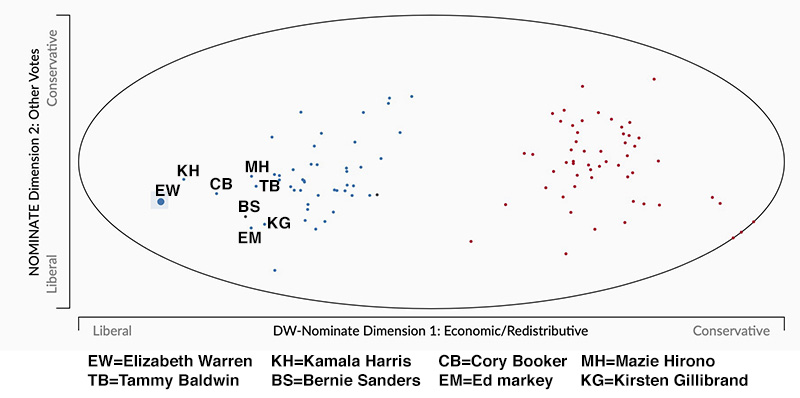

A: We don't recall if we've written an entire item specifically about Warren, but we've certainly written pieces about the methodology that serves as the basis for that assertion. That methodology, first created in the 1980s by Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal at Carnegie-Mellon University, is called DW-NOMINATE (Dynamic Weighted Nominal Three-step Estimation), and it uses sophisticated statistical models to compare the votes of members of Congress to those of their colleagues. The data is now maintained by a team at UCLA, and is available at voteview.com.

For each Congressional term, each member is given a score from -1 (very liberal) to 1 (very conservative). For the four congresses that the Senators have served in together, Warren has scored -0.718, -0.702, -0.783, and -0.799, for an average of -.750, while Sanders has scored -0.599, -0.549, -0.823, and -0.944, for an average of -0.729. Both score very liberal on the scale, but Warren has been: (1) more consistent, (2) much more liberal recently, and (3) more liberal overall. Here are the scores. Note that the most conservative Democrat (Joe Manchin, D-WV) is more liberal than the most liberal Republican (Susan Collins, R-ME), and that Collins (the leftmost red dot) is a far outlier in her caucus.

Q: I think you have touched on this before, but if Elizabeth Warren has jumped back up to frontrunner status in the Veepstakes, can you explain in more detail what would happen to her Senate seat? Does the timing of a resignation matter? A.R., Los Angeles, CA

A: By the terms of (current) Massachusetts law, Gov. Charlie Baker (R-MA) would pick a replacement, and then an election would be held 145-160 days after the resignation.

There is every chance that Warren would "manage" her resignation in order to minimize the service time of the replacement. It's generally agreed, for example, that she could announce her resignation on Nov. 4, but make it effective January 20, and that would run about half the 145-160 days off the clock. Further, the Democrats would move heaven and earth to keep that Senate seat. In the past, the Massachusetts legislature has changed the law as needed in order to advance their (Democratic) partisan goals, and they would presumably do so again. One envisions something along the lines of the North Carolina law, that limits the governor to a list of three names submitted by the party of the departed senator.

Even if the legislature didn't act, the Party would not allow itself to be caught flat-footed the way it was when Scott Brown stole a Bay State Senate seat back in 2010. In fact, since the blue team has two perfectly good Senate candidate facing off right now in the regular Senate race, it's very likely they would just coalesce behind the loser of that contest (either Sen. Ed Markey or Rep. Joe Kennedy III), who would have a massive advantage due to name recognition and near-unlimited funding from the Party.

Q: Has there ever been a time when a VP was chosen and then changed prior to an election? S.B., New Castle, DE

A: Let us start with the caveat that before the party conventions meet, any talk about vice presidents is just that, talk, and has no official significance. This is especially true before 1950 or so, when the job of choosing the Veep was much more in the hands of the conventioneers than the presidential candidate.

What we are saying is that the only situation that qualifies, for purposes of your question, is a candidate being nominated at the convention and then being dropped from the ticket later. And that has happened with a major-party VP candidate exactly one time. In a cautionary tale for would-be presidents everywhere (and one that John McCain did not bother to heed), George McGovern was turned down by several of his top running-mate choices in 1972, and settled upon then-senator Thomas Eagleton of Missouri with virtually no vetting.

Eagleton, as it turned out, had a history of mental health issues, and had been hospitalized several times as a result. Perhaps that should not be disqualifying (and it doesn't appear to be these days), but when this information became public a couple of weeks after the Democratic convention, many voters made clear that they did not want someone with clinical depression one heartbeat away from the presidency. Presumably, they were unaware that some of the world's most accomplished leaders, including Winston Churchill and Abraham Lincoln, battled depression. In any event, McGovern initially stood by Eagleton, but then decided that was untenable, and so Eagleton "withdrew" from the ticket about three weeks after he was nominated. He was replaced by Peace Corps founder, former ambassador and Kennedy in-law Sargent Shriver.

There is another occasion where it almost happened. In September of 1952, the press reported that Republican VP nominee Richard Nixon was on the take, and had been illegally pocketing campaign contributions. Dwight D. Eisenhower had every intention of booting Tricky Dick off the ticket, but the ever-shrewd Nixon managed to arrange things such that he was allowed to go on TV and defend himself prior to having a one-on-one meeting with Ike. The result was the famous Checkers Speech, which won the hearts of Republican voters, and saved Nixon's political career so that he could ruin it another day.

Q: I know the Constitution provides a means for tie-breaking in the event the Electoral College vote is dead-even after a presidential election. But I'm curious if the framers ever considered simply having an odd total of EVs so no tie was possible. Your thoughts? T.H., La Quinta, CA

A: There are pros and cons to each approach. Having an odd number of electors reduces the chances of ties, assuming none of the electors go faithless. On the other hand, it also creates the possibility of a single person having the power to decide a presidential election, which is a situation ripe for corruption. With an even number, it would take two corrupt electors at the minimum, which is at least a slightly taller hill to climb.

In any event, because neither option is obviously "better," the framers did not concern themselves with this question, nor did any of their successors. In fact, of the 58 presidential elections in U.S. history, 30 had an even number of electors and 28 had an odd number, depending entirely on which states (and districts of Columbia) happened to have been admitted at the time of the election. And "even" is only in the lead right now because the current total of 538 has held for the last 14 elections. Before that, it was much more common to have an odd number of electors.

Q: Regarding last Saturday's effort to place Presidents along today's political spectrum, you wrote that 45 different explanations would be dry. But I'm genuinely curious about your grouping of conservative Republicans. What makes them more conservative than Ronald Reagan? R.C., Madison, WI

A: Relying on the above-mentioned DW-NOMINATE scores, as well as other indicators, the Donald Trump version of the Republican Party is as conservative as the Party has ever been, and is arguably as conservative as any party in the United States has ever been. It is nativist, isolationist, anti-tax, anti-government (except military), anti-gun control, and, in many ways, anti-democracy. Not to be needlessly provocative, but Donald Trump is closer to Benito Mussolini or Francisco Franco than he is to Dwight D. Eisenhower or Benjamin Harrison or Calvin Coolidge. Anyhow, in view of this, we placed Trump at the most conservative end of the spectrum. The other presidents we grouped with him (Andrew Jackson, John Tyler, Andrew Johnson) were the others who veered strongly in the direction of right-wing populism.

Reagan has a well-deserved reputation for being conservative, but he grew up as a New Deal Democrat, and that never completely left him. He was in favor of some gun-control measures, supported stem-cell research, adopted a fairly tolerant immigration policy, and was sometimes ok with raising taxes. All of these things are anathema in the modern Republican Party. In fact, it is rather unlikely the Gipper could be elected to the White House as a Republican if his career was beginning right now.

Q: I am curious about your placement of Andrew Jackson in the extremely conservative political

party. Although Donald Trump seems to idolize Jackson (to the extent that people told him to), I do not think that Jackson

would appreciate that. A greater comparison to Jackson is Lincoln. Both Jackson and Lincoln believed in a very strong

executive branch in a strong national government. Neither of them wanted strong state governments. Both Jackson and

Lincoln (and Washington) were willing to use strong executive action to stop states from defying the national

government. Both Jackson and Lincoln were willing to go to extra-legal lengths to make certain that their ideas were

carried out.

Meanwhile, I am fairly certain that both Franklin Pierce and Lincoln would be appalled to be placed in the same party.

Franklin Pierce's actions with the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the expansion of slavery into land where it had been outlawed

essentially destroyed the Whig Party and created Lincoln's Republican Party. Without that law, uniting the various

anti-slavery groups of the country would have been much more difficult.

J.B., Pinckney, MI

A: You're trying to have it both ways! The Whig Party was founded specifically as the anti-Jackson Party. You can't ignore that sort of dynamic when you put Lincoln and Jackson in the same party, and then take note of it when you object to our putting Pierce and Lincoln in the same party.

In any event, we don't think that belief in a strong central government is all that significant. True, that was a big political issue of the 19th century, but most presidents of the last 200 years have favored a strong central government—at least, when it was using its power to do the things they wanted done. After all, Barack Obama and Donald Trump both believe in a strong central government, they just differ significantly in how that power should be used.

And that is the rub when it comes to Jackson and Lincoln. Other than maintaining the union at all costs, they did not much agree about how federal power should be used. Jackson was an isolationist, Lincoln wasn't. Jackson favored a laissez-faire economy, Lincoln favored a centralized economy (and even oversaw the passage of the first income tax, which would have caused Jackson to blow a gasket if he were still alive). And perhaps most important, Jackson—like Donald Trump—was largely only interested in governing for the benefit of his base. Everyone else was to be ignored (if they were white), enslaved (if they were black), or wiped out (if they were Native American). Lincoln, by contrast, was vastly more inclusive. He was tolerant of Native Americans (relative to other leaders of his day), abhorred slavery (and eventually set it on the path to destruction), and cared deeply about creating equality of opportunity for the working man.

As to Pierce, he was one of the most difficult presidents to categorize. However, we was pro-labor and anti-big business, which suggests Democrat. Further, something we considered a bit when putting together our list was the candidate's home state. Pierce wasn't really an ideologue; he was a pragmatist who moved with the political winds and tried to stay in sync with his constituents. And our guess is that someone like that, if they were alive today and representing New Hampshire, would be a centrist Democrat.

Q: Calvin Coolidge, the darling of fiscal conservatives and limited government would be better in Moderate Republican than a Centrist Republican. J.M., New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, Canada

A: Another tricky one, and another whose home state (Massachusetts) entered into our thinking a little bit. Also, he was willing to call for greater civil rights for people of color all the way back in the 1920s, going so far as to declare that their rights are "just as sacred as those of any other citizen" in his first State of the Union address. Anyhow, between the fact that he represented a (now-deep-blue) state, and his views on civil rights, that pushed him just over the line into "centrist" for us. But you make a good case, and we don't feel too strongly one way or the other.

Q: A good case can be made for moving Nixon from "Centrist Republican" to "Centrist Democrat." He opened up relations with China for the first time since 1949. He supported a universal basic income at one time during his presidency. He signed legislation creating the EPA. He signed the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts. He signed Title IX and started a number of arms-control initiatives with the then-Soviet Union. He signed the Endangered Species Act and OSHA was created during his administration. It's just about impossible to see anyone in the modern GOP supporting this kind of agenda. L.R.H., Oakland, CA

A: You're right, he also had a remarkably progressive attitude when it came to drug addiction, and he worked hard to try to help Native Americans (see the Indian Financing Act of 1974, for example). That said, his approach to the Vietnam War brings to mind the worst elements of neoconservatism. And he pursued an overtly racist politics (while also trafficking in anti-Semitism in private). Further, his notion that "if the president does it, it's not illegal" brings another president to mind, and that president is no Democrat. In the end, we felt the policies on war, race, and presidential power were ultimately more consequential, and so were determinative.

Q: I'm sure you'll get a flood of these kinds of questions, but one of your "past president" classifications that really stood out to me was putting Jefferson as a liberal Democrat. On the one hand, his embrace of Englightenment philosophy, supposed pacifism, and his words (not necessarily actions) in favor of equality beyond the standards of his day might put him in the progressive camp today. On the other hand, his concern for individual liberties and states rights, uneasiness with centralized federal power, and idealization of agrarianism would be much more right-wing than left-wing today. I've always seen political views less as a spectrum and more as a circle, in which you get some overlapping principles by moving both far enough rightward and far enough leftward around the circle But when you put together Jefferson's political views, it seems to me that he would be closer to a Libertarian than a liberal Democrat. Can you elaborate on why you classified him as you did? N.S., Milwaukee, WI

A: As we argue above, we don't think views on federal power are all that instructive, since most presidents warm up to the idea of a strong federal government when it suits their needs. For example, the Louisiana Purchase was certainly not the act of a weak federal government.

Ultimately, we could not help but notice how much Jefferson has in common with...Bernie Sanders. Pro-rural/agrarian. Devoted to the "little guy." Pretty good on civil rights in words, less substantive in actions. Suspicious of big business and the business class. Outspoken. Irreligious.

We also agree entirely that the "spectrum" is more of a circle, and that the far left and far right have much more on common that either of them would prefer to admit. This is why the defection of many Sanders supporters to Donald Trump in 2016 is not so surprising. It's also why Jefferson has fond admirers among liberals (like William Jefferson Clinton) but also among conservatives (like Ronald Reagan).

Q: The piece attempting to re-categorize presidents based on modern party alignments was very

interesting. I wanted to ask about your reasoning on two: FDR being a moderate Democrat and Wilson being a centrist

Republican.

I would have expected the man who created Social Security and oversaw an unprecedented expansion of the federal

government to be in the liberal category. He was certainly pragmatic, but that sounds like Elizabeth Warren to me.

Wilson had extremely conservative views on race, but he's also (with the possible exception of Teddy Roosevelt) the

president most associated with progressivism (Teddy's record on race isn't exactly shining either, and there are three

that you put to Wilson's left who, you know, owned people). I would have put him as a moderate Democrat at the very

least.

J.W., Indianapolis, IN

A: It is true that FDR dramatically expanded government power, and successfully shepherded many left-wing policy ideas through Congress. However, he prioritized pragmatism so highly, he just seemed a little more Clinton-esque than Warren-esque to us. The Warren-esque person in that White House was Eleanor Roosevelt, who was clearly more liberal than Franklin. Or, put another way, if you put FDR in the "liberal Democrat" camp, where do you put Eleanor?

As to Wilson, it's true that he is heavily identified with progressivism, but that is somewhat misleading (and, in fact, we would argue that William Howard Taft was actually more progressive than Wilson). To use modern nomenclature, Wilson was very liberal on fiscal issues (taxes, government involvement in the economy, business regulation), but very conservative on social issues (opposed women's suffrage, segregated the federal government, staunchly anti-immigrant). Averaging out the two extremes argues for centrist of some sort. And his Latin American policy, which echoes Republican nation-building efforts in Iran (Eisenhower), Nicaragua (Reagan), and Iraq (Bush 43), was what broke the tie in favor of Centrist Republican.

Q: I wonder if you could add Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin to the list of re-alligned presidents. Where would they stand today? M.B., San Antonio, TX

A: Well, Hamilton was one of the earliest advocates of a centrally managed economy, was one of the first prominent Americans to call for an end to slavery, and was sympathetic to immigrants. As someone whose education was funded by others, he was a strong advocate of public education (including public university education). On the other hand, he loved big business, and he pushed for stronger law enforcement (unfortunately for him, police departments, as we know them, did not emerge until after his death). Anyhow, that looks an awful lot like a description of...Bill Clinton. So, we'll go with centrist Democrat.

Franklin is a very interesting case. He was a wildly successful businessman, which means "Republican" today, more often than not. That said, Franklin was militantly pro-science, and so would surely not be caught dead in today's Republican Party. Talk about being pro-science, how many modern Republicans would go fly a kite in a thunderstorm because they were curious about what lightning was made of? He was also an early advocate for abolition, and was very liberal on gender issues (and, for that matter, sexual morés). As a long-serving ambassador, he was a big believer in alliances, treaties, and international cooperation. Oh, and he had a decidedly socialist streak, as evinced by his work founding Philadelphia's first fire department and first library, not to mention its first university. Excepting the propensity for, well, wild sex orgies, Franklin seems much like an 18th-century version of...Bill Gates. And Gates is pretty clearly a Liberal Democrat.

Q: I noticed in answering J.N.'s question, you broke down both parties as moderate and centrist. I've never seen that before, and thought they were one and the same. Wikipedia says: "Voters who describe themselves as centrist often mean that they are moderate in their political views," which implies they are indeed one and the same. How do you differentiate "centrist" and "moderate"? R.K.P., Chicago, IL

A: Wikipedia is generally ok on facts, but is often shaky on abstract concepts, so we wouldn't necessarily go by them here.

Anyhow, by "Moderate," we meant "someone who adheres to the mainstream position of their party most of the time." By "Centrist," we meant "someone who adheres to the mainstream position of their party some of the time, but also crosses party lines on a few big issues." We found that usage to be clearer and more readable than the alternative, which would have been to relabel the centrist factions as "Conservative Democrat" and "Liberal Republican."

Q: I am truly fascinated with by the poll that shows Jaime Harrison being in a virtual tie with Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) in the South Carolina Senate race. An upset victory there against such insurmountable odds would be an incredible story for many years to come. Would you be able to give us some of your best examples of similar political races in our country's history, where an unknown candidate came out of nowhere and beat a very strong incumbent to win a Senate or a Congressional seat? M.D., San Tan Valley, AZ

A: The "polling era" begins in 1950 or so, which means that the answers to your question pretty much have to come after that year. Prior, it was difficult for upsets to be too noticeable, as there was no clear way to distinguish between "underdog," "big underdog," and "massive underdog."

Anyhow, with that said, here are five notable upsets, in chronological order:

- Paul Wellstone, 1990: Wellstone (DFL) was a very liberal, wonky college professor with no

money when he declared for Minnesota's Senate seat. Rudy Boschwitz (R-MN) was a two-term incumbent and a

multi-millionaire who had the full backing of his party. Although Wellstone was outspent by a margin of 7-to-1, he

successfully ran the playbook that Bernie Sanders tried (with less success) to run during his presidential campaigns,

getting young voters excited and then getting them to the polls. Boschwitz' surrogates also made the error of

questioning Wellstone's Jewishness, since he married a non-Jew. This did not go over well with Jews or non-Jews. When

the votes were counted, the college professor trounced the wealthy Senator by nine points.

- Harris Wofford, 1991: After Senator H. John Heinz III (R-PA) died in an airplane crash in

May, then-governor Bob Casey (D-PA) appointed Wofford (D) to the seat until a special election could be held in

November. We all know that appointed senators are a crapshoot, and in this case, the Republicans brought out the big

guns, picking Dick Thornburgh as their candidate. He had served as governor of Pennsylvania and as U.S. Attorney

General, and was widely regarded as an eventual GOP presidential candidate. Early polling had Wofford down as much as

40 points, but he hitched his wagon to the issue of universal healthcare, and ended up winning by 10.

Though Wofford did not last beyond that term (losing to Rick Santorum in the next regular election), that election nonetheless ended up being rather consequential from a presidential perspective. To start, it brought an end to the talk of Thornburgh for president, and many Republican movers and shakers began casting about for someone else to groom for the job. The fellow that many of them settled on was...George W. Bush. Meanwhile, the two men who managed Wofford's miracle win caught the attention of a lot of prominent Democrats, who said "I might like someone like that to work for my campaign." Those two men were...James Carville and Paul Begala. - George Nethercutt, 1994: This election was the biggest Republican wave in recent history,

as members of the party, following a strategy laid out by Newt Gingrich, ran for Congress by running against the

institution of Congress itself. Of course, who is more emblematic of Congress, as an institution, than the Speaker of

the House of Representatives? And that is what allowed a political unknown like Nethercutt (R), whose only public

service before that was a few years as a congressional aide, to knock off Speaker Tom Foley (D-WA). That's only the

third time a sitting Speaker of the House has been defeated in a reelection bid, and the other two (William Pennington

of New Jersey and Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania) barely count because they both served during the Civil War.

- Melissa Bean, 2004: Then-representative Phil Crane's (R-IL) seat was a safe Republican

seat for many years, allowing him to emerge as one of the House's true conservative firebrands (think Matt Gaetz, R-FL,

or Jim Jordan, R-OH). However, he slowly got out of sync with his constituents, such that he was got a real challenge

from Melissa Bean (D) in 2002, and then he was defeated by her in a 2004 rematch. That was a presidential year, and

George W. Bush won the then-solidly Republican district. However post-election analyses showed that Bean was assisted by

the coattails of the Democrat who won that year's U.S. Senate race in Illinois. His name was Obama; our staff researchers are

looking into what became of him.

- Dave Brat, 2014: This is the sibling of the Nethercutt upset. In this case, the victim was House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R). That's a lower rank than Tom Foley held when he got booted, but at least Foley made it to the general election. Cantor got primaried, as his centrist brand of Republicanism left him out of step with the strong tea party forces in his district. That allowed ultra-conservative economics professor Dave Brat (R) to knock him off. Cantor was so upset by his upset that he resigned from office immediately and did not finish his term.

And yes, we could very well have put Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez' (D-NY) surprise primary win over Joe Crowley (D) on the list, but we figure that one is recent enough that most folks know about it, and that older examples are of more interest.

Q: I'm wondering if you have ever dealt at all with Allan Lichtman's presidential race predictions. Do you ascribe to his 13 keys as a reasonable predictor for an election? Why or why not? P.R., Saco, ME

A: We haven't written much about Lichtman, which kind of implies the answer to the balance of your question, namely that we actually don't think too much of his method.

To start, we would argue that his "track record" has been greatly exaggerated. Yes, when it came time to cast ballots, he was on the right horse in eight of the last nine elections. However, seven of those were not really close, and so getting them right is not especially impressive (especially when one is only picking a winner, and not something more specific, like an electoral vote tally or a margin of victory in the popular vote). Of the two really close elections in that time, he got one wrong (2000) and one right (2016). You know another technique for achieving a 50% accuracy rate in close elections? Flipping a coin.

Meanwhile, the method itself is too...squishy, for lack of a better term. A lot of the "keys" are semi-subjective, like "There is no serious contest for the incumbent party nomination" or are entirely subjective, like "The incumbent party candidate is charismatic or a national hero." And what is really going on is that Lichtman is making a "gut feel" judgment, and then cloaking it in a veneer of analytic rigor and objectivity. Gut feel is a perfectly valid approach—that's what Sabato's Crystal Ball and the Cook Political Report do, for example—but it's a bit disingenuous to pretend that your "gut feel" is something more digital.

Q: What motivates an organization to begin a poll, and who pays for that polling? And what do pollsters and polling companies do between election years? R.M., Baltimore, MD

A: We can think of four major reasons that polls are conducted (and paid for):

- A scholar and/or a university are interested in publicity.

- A news organization needs something to write/talk about.

- A pollster is advertising their services.

- A political campaign, committee, or other entity is looking for tactical information.

It could be more than one of these, of course, depending on the poll.

As to the second part of your question, there's usually enough work to keep purely political pollsters (like, say, Ann Selzer) occupied even during lulls in the cycle. After all, there's always an election around the corner, plus there are approval ratings, and so forth. However, most non-academic pollsters (like, say Gallup) actually do many types of polling and/or market research. Consistent with item #3 on our list, their political polls are largely meant to make potential customers aware of their range of services.

Q: Interested in your

comments

on the recent Civiqs poll of South Carolina, I read further and noted it was an online poll.

You wrote that the pollster—Drew Linzer—has some credibility behind him, and opined that his model is likely

accurate. But how should we balance the gravitas of a seasoned statistician on one hand, with the notoriety of online

polling on the other, when interpreting this poll?

D.C., Portland, OR

A: To employ a rough analogy, we might compare a traditional poll to driving a car with an automatic transmission, and an online poll to driving a car with a stick shift. If you have a lot of experience and skill with the former, you have a pretty good chance of being able to navigate the greater challenges of the latter.

That said, we try to evaluate polls holistically, taking into consideration as much information as we can get. So, the pollster's track record is important (if we can discern it). Generally, if FiveThirtyEight gives a pollster a rating lower than C- (based on its calls in past elections) we won't use it. But we also try to figure out what their motivations might be. If they are an academic, or are working for a news-gathering organization, a pollster is less likely to cook the books. If they are an activist, or are working for a political party, a pollster is more likely to cook the books. Many "pollsters" are really campaign consultants and openly advertise whose team they are on. Look at the client list of McLaughlin and Associates, for example. It lists the RNC, NRSC, NRCC, and 10 state Republican parties it has worked for, along with nine sitting Republican senators, 18 sitting Republican representatives, and dozens of former Republican members of Congress. Imagine you are a Republican running for Congress. Would you feel comfortable hiring Mr. McLaughlin? Very likely so. Not so much if you are a Democrat though.

Also very important is the smell test. If a poll, particularly one from a pollster whose track record and source of funding are hazy, produces results that are at odds with everything else we know (say, a poll has a Democratic U.S. Senate candidate up by 10 points in Mississippi), we tread lightly. Similarly, we examine whether the poll's numbers make sense internally. In the case of that Civiqs poll, as we noted, we thought it was instructive that they had the Senate race close but not the presidential race. That is at least some evidence that their model of the electorate is not completely wrong. In general, the rule is "innocent until proven guilty," meaning that if there is no clear reason to exclude a pollster, we accept them.

Q: Just curious why the recent Utah Policy poll of Utah isn't included in your database. Every now and again I see what appears to be reputable non-partisan polls reported by PoliticalWire that are not included on your site, and I've never known that site to report non-reliable information. D.C., Filer, ID

A: Y2 Analytics is a bit of a hybrid. It has many big companies for clients and a small number of (Republican) politicians. Our first instinct was: "Hmm, only Republican politicians = fishy." But checking them out more carefully, the team also work for Amazon, Microsoft, Nike, Haagen-Dazs, Adidas, Comcast, Uber, and many other big companies. These guys aren't going to put up with someone who cooks the books. So why do they do a small amount of political consulting only for Republicans in Utah? Maybe there aren't so many Democrats in Utah. After reevaluating, we'll put them in. Also—and this plays a role—there are so few polls of Utah that even a potentially biased poll is probably better than just using the 2014 election results. In a state like Arizona or Florida, which is polled almost every week, we can afford to be much pickier.

Q: The comment from B.B. from Lees Summit, MO, got me to wondering: when readers like me submit comments or questions, do you vet them in a cursory manner, to ensure they are not "ringers" or imposters? I would assume trying to do a quick Internet search on all of the submitting readers would be overwhelming and possibly fruitless. But how do you know you are not being "played?" Do all submitters provide their full names, or only initials? L.E., Santa Barbara. CA

A: Most of the time, we do know the person's name, home city, and e-mail address (though sometimes folks forget to include one of those things). Also, many correspondents have sent in multiple messages, so we have those to judge by, as needed. Beyond that, it's usually clear when a question/comment is a little snarky or has a little bit of subtext (as with the question from D.A. above, for example), and when a question/comment is entirely insincere and exists only to be insulting or to engage in some other form of trolling.

There are many things we publish on weekends, particularly on Sundays, that we do not agree with or that we think are wrongheaded. However, we are always very close to 100% certain that the person writing in believes in what they are asking/saying.

Q: I've noticed that over the last four years (or is it 40, nobody's sure) there's gradually been a more...humorous but frustrated sarcastic tone to your posts. I imagine that having to cover U.S. politics daily must be a tremendous mental load just now. Are you both doing all right? How do you keep yourselves going? D.N., Boston, MA

A: We are just fine. The bad behavior we see from some partisans these days is more damaging to us as citizens of the United States and of the world than it is to us as writers and scholars.

As to the higher level of sarcasm, that's a product of three things. The first is the obviously different character of this presidency as compared to others. We would not have been snarky at all about a President Jeb Bush. He is a serious politician and an honorable person. The second is that there are certain things (outrageous tweets, baldfaced lies, poorly thought-out executive actions) that happen so often, it's hard to keep the coverage engaging without using different styles and tones. The third is that (Z) joined the site right around the time the rise of Trump began, and he is more prone to sarcasm than (V) is. You should have seen the joke that (V) struck yesterday, which (Z) knew full well was just a little too sarcastic. Here's a hint: It involved an observation about one presidential ticket having a combined 150 years on the planet and the other one having a combined 150 points of IQ.

Q: This might fall under a behind-the-scenes type of question, but have either of you given thought to what you might do with the site if Joe Biden wins the presidency? In election cycles past, that has usually been a time when you have tried to reduce the number of postings. As a loyal reader, I've come to look forward to each day's post and would hate to go back to the occasional posting schedule (this is assuming that a Biden presidency will look a lot like an Obama presidency). Have you thought about mixing in other materials, like the history pieces, if we go back to a normal presidency? D.E., Lititz, PA

A: We're usually so busy that it's hard to think a week ahead, much less six months ahead. That said, even if a hypothetical President Biden delivers far less shocking behavior, there will still be plenty of material to fill the site with. And it's also a two-man operation now. So, while a slightly reduced publication schedule is possible, full darkness is not likely.

Q: Let us assume the very unlikely to nigh impossible—in 20 years, there is a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College. Your site is still up and being run by the two of you (may you live forever). Will you change the name? If so, to what? J.C., Binan, Laguna, Philippines

A: 21st Century Fox? That's not taken.

As we said above, it's hard to think a week ahead, much less a generation. That said, like 20th Century Fox, we're pretty much stuck with our brand, even if that brand ceases to make much sense.

Today's Presidential Polls

Here is the poll we were initally sceptical of. We have set up the software to flag unlikely results in order to catch typos. If a poll of Idaho shows Biden 65% and Trump 35%, maybe we ought to check to see if perhaps we reversed the numbers by accident. Well, it had a fit with this Utah poll, so we told it shut up and just add it. Clearly something is going on in the red and purple states. Biden has led all year in Florida, North Carolina, and Arizona. Georgia is a tie now and Texas has been a tie. So maybe the Utah poll is right and even red states aren't happy with Trump right now. Let's hope more red states are polled soon. (V)

| State | Biden | Trump | Start | End | Pollster |

| Utah | 41% | 44% | May 09 | May 15 | Y2 Analytics |

Back to the main page