Previous | Next

Saturday Q&A

Same structure as the previous two weeks: COVID-19, then more general election stuff, then history, and finally a few "behind the scenes" questions.

Q: We have now seen three governors' pacts to coordinate their economic re-openings (West Coast, East Coast, Midwest). This to me looks like a clear rejection of federal authority. If Donald Trump orders the economies of those states to reopen and they ignore that order, it could set up quite the fiasco. Given that Trump hates to be made to look a fool, I could see him trying anything he can to bend the states to his will. Could I be the only one thinking this could lead to a "cold civil war" of sorts? I am not sure there is any chance of a hot one at this time, but this is becoming very bizarre. What options does Trump have to force states to follow his orders? A.G., Santa Clarita, CA

A: In fact, there isn't all that much that Trump can do to bend states to his will. We would suggest two obvious pieces of evidence this is the case. The first is that, if he had that power, he would have used it with immigration and the so-called "sanctuary cities." The second is that he unwisely declared that he has "total authority" over the states earlier this week, and then did a speed-of-light 180-degree turn on that. This was an obvious face-saving move, as it spares him from being asked every single day about why he's not exercising his "total authority."

There are at least two major reasons Trump's power is limited here; one of them general and one of them specific. The general reason is that the United States, being a federal system, does not give presidents all that much power to compel obedience from the states, except in specific areas claimed by the federal government (for example, regulation of interstate commerce). Instead of taking some sort of punitive action, he could take some sort of punitive inaction, like withholding funding (which is what he tried to do to California in response to the state's defiance of his immigration policies). However, this is a generally tenuous course of action that runs afoul of Congress' power of the purse, and that is not likely to be upheld by the courts. In the middle of a pandemic, it would also be terrible optics. He can also do things like commandeer (i.e., steal) medical supplies that blue states have ordered and paid for and redirect them to red states, but again, the public might side with the governors when they start screaming.

The issue that is more specific to the current crisis is that even if Trump finds some basis to flex his muscles (say, declaring martial law), that is still significantly limited by the willingness of the citizenry to comply. If millions of people do not believe they are safe going out in public, going to restaurants, going to school, going to work, etc., what can the government do? Go door-to-door and force them out of their homes? That is both highly illegal and highly impractical. The same dynamic is at play in recessions and depressions: The federal government can encourage people to spend money and to participate in the economy, but it can't force them to do so.

What this means is that the most powerful tool that Trump really has is the bully pulpit. He can command a national audience, every single day, for whatever he wants to say about COVID-19. And your observation about a "cold civil war" appears to have been prescient, because mere hours after saying that he was deferring to the state governors and was encouraging people to stay at home at least through the end of April, Trump sent out tweets encouraging people in Minnesota, Michigan, and Virginia to rebel against their state governments' stay-at-home orders. He even specifically invoked the Second Amendment, which is pretty obviously a call for violent rebellion. That is supposed to be illegal, but undoubtedly the Republicans in Congress won't think twice about it. As to everyone else, there is no doubt that some portion of Trump's base will respond to his encouragement, whatever he tells them to do. However, the rest of the base, and pretty much everyone else, will take their own counsel and that of leaders who do not reverse course on a daily basis.

Q: Your site is part of my daily routine since the election when Bush was declared the

winner over Gore by the Supreme Court. At the time, I lived in Florida, and I am still peeved that my vote was

never counted, and that Gore may have actually won the election had they just counted all the votes.

Now I live in Puerto Rico. I see that you have the primary map of elections on your site, but leave off

Puerto Rico, which has more electoral votes than the majority of states. Puerto Rico also has a debt problem.

However, unlike states, Puerto Rico cannot declare bankruptcy to restructure their debt, and so we maintain

$70+ billion in debt. As this amount is a drop in the bucket when it comes to the past 3 rounds of COVID-19

relief, why are no lawmakers talking about debt relief for Puerto Rico? Puerto Rico, previous to the virus,

already had the highest unemployment in the USA. They also are saddled with the Jones Act and pay more into

social security than they receive. A large part of the economy is built around tourism, which has been hit

especially hard. Meanwhile, Puerto Rico still has the labs and manufacturing (from their previous background

as a pharmaceutical tax haven) to become the center for making COVID-19 tests or medical supplies, and

yet few are talking about this. In addition, Puerto Rico has voted twice for statehood, and yet Congress has

taken no action. The next relief bill could and should include several steps to address the above.

R.V., San Juan, Puerto Rico

A: Let us note an important error in your question. Puerto Rico awards 59 Democratic presidential delegates and 23 Republican presidential delegates, but it has zero electoral votes.

And therein lie the reasons that the politicians don't especially concern themselves with the issues of Puerto Ricans. First, they currently have no actual political power. The next time their presidential delegates actually matter will be the first time. Second, if given any actual political power, they would undoubtedly use it mostly to the benefit of Democrats. And so, the Democrats would love to add Puerto Rico as the 52nd state (after Washington, D.C., which is even bluer, as the 51st). Then the country will be like a deck of cards. The red states will claim the red cards and the blue states will claim the black cards. California will claim the most powerful card (the Ace of Spades), and Texas will be the Queen of Hearts.

But the Republicans are never going to go for it, and if the Democrats try to get that done in COVID-19 relief bill v4.0, the red team will scream bloody murder about how the blue team is using a national crisis to try to increase their political power. Also not helping is that anything done for the benefit of Puerto Rico—forgiveness of debt, investment in medical infrastructure, etc.—would have to be signed into law by a man who has little interest in giving money and resources to brown people who will not be voting for him when there are perfectly good white people who could also use that money and those resources, and who will vote for him.

As to Puerto Ricans voting for statehood, those various elections have been questionable enough that they would be challenged in court, and they might not stand up. So, the commonwealth would probably need to hold another plebiscite that produces a crystal-clear result.

Oh, and we don't have Puerto Rico on our map because it would be implausible from a design standpoint. We would then have to include Guam, and American Samoa, and the Morthern Mariana Islands, and so forth, and it would be too much clutter. Also, for national convention purposes, Democrats Abroad is a state, but Republicans Abroad is not. How would we illustrate that? Someone in blue clothes holding up an American flag in front of the Eiffel Tower? If Puerto Rico does become a state, though, then it will likely get the Alaska treatment (a.k.a. a box in the corner). And if that's not motivation to press for statehood, we don't know what is.

Q: Is it possible that Donald Trump is not only not pushing the CDC or FDA or whoever would be responsible to create and manufacture COVID-19 tests, but that he is discouraging them or inhibiting them from doing so? Is it possible that he is doing this to "keep his numbers down" and therefore add some legitimacy to his quest to relax restrictions? J.N., Blacksburg, VA

A: Is it possible? Certainly. He clearly has no issue with undertaking unethical or dishonest behavior in service of his own needs, even if that behavior costs lives (see, for example, Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria). That said, we don't think it's likely. First, because a conspiracy is only as strong as its weakest link. If Trump puts his thumb on the CDC or FDA, there are folks there who would surely blow the whistle. Second, because this wouldn't actually do the President all that much good, as states are taking steps to acquire or create their own test kits and their own data.

Q: We seem to be headed toward a fitful "reopening" of the country in as little as two weeks' time. What I don't understand is why the GOP propaganda machine, presumably with the blessing of the oligarchy that sustains it, is cheerleading for this idea, as it goes against their interests politically. I can believe that Trump is delusional enough to think that nothing will happen if people fill the streets again. But the Ingrahams and Limbaughs of the world (to say nothing of the Murdochs and others whose names we barely know) are not stupid. They know that only massive testing and case tracking can get the economy back to a condition that might save Trump's bacon in November. Tens of thousands more unnecessary deaths will certainly doom him. It wouldn't be hard to put some self-serving spin on it, like "the Chinese and the U.N. and the Democrats got us into this mess, so now we have to do this as much as we hate it." Why aren't they taking this approach? C.C., Los Angeles, CA

A: We think you might be assuming facts not in evidence. For example, we've seen Laura Ingraham's program a number of times. If she is merely playing dumb, then they ought to give her an Academy Award right now. More significantly, we see no evidence that any of these folks—Trump, or right-wing pundits like Limbaugh, Ingraham, Ben Shapiro, Hugh Hewitt, Sean Hannity, etc.—think long-term at all. They figure out what will get their audience going today, and they don't worry about what they're going to say next week or next month. This is why all of these folks get caught, all the time, saying "X" and then later saying "the polar opposite of X." And their solution, rather than working harder to be consistent, is to gaslight everyone and to claim they have always advocated for "the polar opposite of X." This is how, for example, Hannity goes from "COVID-19 is no big deal" to "I've always emphasized what a big deal this is" in two weeks.

With that said, if there is any sort of long-term thinking here—and again, we don't believe there is—it would go something like this: COVID-19 is likely to hit blue states harder than red states because the blue states are more urban and thus more densely packed. So, the right-wingers encourage states to reopen, and some of the smaller, more sparsely populated red states follow suit. Then, if there is no huge outbreak in those red states (because they are sparsely populated) and there is no huge outbreak in the remaining states (because of them imposing stringent measures for citizens' protection), Trump and his friends in the media can claim that this whole thing was no big deal, that it was really no different from the flu, and that it was all a Democratic overreaction.

The problem with this plan, such as it is, is that COVID-19 cases are currently spiking in red states without stay-at-home orders, much more so than in the rest of the states. Also, Texas has big cities, and spikes in Houston, Dallas, Austin, Fort Worth, and San Antonio wouldn't look so great for Texas.

Q: Could you please clarify the popular conflation of COVID-19 with the garden-variety flu? Exactly how is it different? J.R., San Francisco, CA

A: To start, "the flu," which is actually a whole family of diseases, has been studied closely for a very long time. That means that it's pretty well understood, there is some level of herd immunity, there is a fairly effective vaccination strategy, and medical professionals know how to manage (if not resolve) its symptoms fairly well. This translates, in an average year, to something like 35 million people getting sick, 500,000 of those ending up in the hospital, and 35,000 people dying in the United States.

COVID-19, by contrast, is of recent vintage (as its name indicates, as the '19' stands for '2019'). That means that it is not well understood. In particular, the questions of why some people are affected much more than others, and why the afflicted often go from "moderately sick" to "at death's door" in a matter of hours do not yet have good answers. There is no vaccine, along with virtually no herd immunity, at the moment. Doctors can still manage symptoms (after all, fever or breathing difficulties are generally treated in the same manner, regardless of underlying cause), but are currently being hindered by lack of space, supplies, and skilled labor. Exactly how bad it will be, statistically, is unknown. However, according to the statistical aggregator being maintained at Wikipedia, the current number of known cases in the U.S. is 706,880, resulting in roughly 100,000 hospitalizations, and 32,230 people dead. All of those numbers are undoubtedly low, especially the first and third ones. However, even if we go only by known incidences, COVID-19 is clearly going to do much more damage than the flu will this year.

In short, the two diseases are pretty different in terms of our knowledge about them, our ability to combat them, and the impact they will have in the next 6-24 months. They are also quite different at a cellular level. Without getting into the weeds too much, most different strains of flu are the product of reshuffling of H and N antigens (which is why swine flu is called H1N1, for example). This means that last year's major strains of flu, this year's strains, and next year's strains are all different, and all require a different vaccine (which scientists figure out by testing birds and other animals in spring of each year). Consequently, while individual strains of flu may be well managed, "the flu" will never be eradicated, and most strains are serious enough that vaccination is an appropriate precaution. This is why people get annual flu shots, compared to one or two shots in a lifetime, as with polio or measles.

With coronaviruses, the mutation process is much different, with the result being that there are many more varietals than with the flu. The good news is that most coronavirus strains are much less serious than the flu, and vaccination is not necessary. The bad news is that there is an occasional coronavirus strain that is really serious, like COVID-19 is. What makes this varietal particularly nefarious is that it's very contagious and that it manifests limited (or no) symptoms for an extended period, making it very easy for someone who is ill to spread unwittingly. The time will come when a COVID-19 vaccine is developed and, between that and herd immunity, the disease will be significantly contained or even eradicated. Then, there will be a whole bunch of new coronaviruses next year and the year after and the year after, and they will be no big deal. Eventually, though, another really serious one will emerge, maybe in 5 years, maybe in 10, maybe in 50.

As a reference point, the last really serious coronavirus organisms to emerge were the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012 and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) in 2002. The organism that causes COVID-19, in fact, is formally known as SARS-CoV-2. You might notice that the factor that tends to separate the really bad coronaviruses from the less bad is that the former tend to trigger severe, as opposed to mild, respiratory distress. Hopefully, we will be better prepared when SARS-CoV-3 or MERS-CoV-2 emerges, whenever that might happen.

And finally, if someone conflates the two diseases, we can only see three explanations: (1) they don't know what they are talking about, or (2) they are trying to downplay the seriousness of COVID-19 for political purposes, or (3) all of the above.

Q: I very much appreciate you continuing to respond to the questions of what happens if

there's no election.

In each response, you point out that there's a good chance the Presidency could ultimately fall to a Senate

President pro tem chosen by those Senators whose terms had not expired, and that this partial Senate would be

composed of 35 Democrats/Independents and 30 Republicans.

However...once January 3 passes and the seats of Class 2 are declared vacant, governors would surely move

quickly to begin appointing replacements as permitted by the Constitution and state law, especially if the

Presidency was at stake.

Currently, 3 of 12 Class 2 Senate seats currently held by Democrats are in states with Republican governors

(Alabama, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire), and 6 of 21 Class 2 seats held by Republicans are from states

with Democratic governors (Colorado, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Montana, and North Carolina). There are also two

special elections for Class 3 seats, both currently occupied by Republicans with Republican governors.

On paper, this suggests 15 Democratic appointments and 20 Republican appointments, resulting in a 50-50

tie. The wrinkle is North Carolina, which requires an appointment of the same political party, giving the GOP

a 51-49 edge.

A.L., New York, New York

Q: If there is no election, and the choice is placed in the hands of the Senate by virtue of picking the pro tem, can the Republicans pull some sort of shenanigans like staging a walk-out of their Senate caucus to deny a quorum to choose a Democrat? Or is the quorum based on the number of sitting senators at the time (meaning 32 or 33 of the remaining 65, including the two independents)? Would it serve any purpose to do so, even if it's possible, since the line of succession moves to the cabinet after the SPPT, whose terms would also (presumably) be expired, as well? D.F., Norcross, GA

A: In response to A.L.'s question, we will begin by mentioning one name: Roland Burris. Thanks to Powell v. McCormack (1969), the power of Congress to refuse to seat elected members is very limited. However, Burris was not elected; he was appointed to replace Barack Obama under dubious circumstances. So, when he presented his credentials on January 5, 2009, they were deemed invalid, and Burris was sent home to straighten things out. It took a week for him to get a court order validating his appointment.

Democrats do not generally like to engage in heavy-duty trickery, but if the Republicans and/or Donald Trump try to steal the election, all bets are off. And temporarily refusing to seat members, on the basis that their appointments are not legitimate, would buy the blue team just enough time to take care of business and pick a Democratic pro tem, and then to change any Senate rules they need to change to keep that person in office ("henceforth, upon election, a president pro tem can only be removed by death or by a vote of three-quarters of the Senate"). This, then, returns us back to our general argument that for every Republican move available, there is an effective Democratic counter-move.

Moving on to D.F.'s question, what you are describing is called quorum-busting, and it wouldn't work. As you (correctly) infer, when seats are vacant, the number of senators needed for a quorum drops commensurately. So, the 35 Democrats plus independents would be enough to conduct business in the event no election is held and multiple dozens of seats are left vacant. There are two other wrinkles, beyond that, that would both work in the Democrats' favor. First, by Senate rules, a quorum is assumed to exist unless someone specifically asks for a head count and/or a roll call vote and demonstrates that it doesn't. If there are zero Republicans, then nobody would ask for a head count, and a quorum would be presumed to exist. Second, also by Senate rules, if senators are trying to quorum-bust, the sergeant at arms is empowered to find them and arrest them. If you'd like to read (a lot) more, here is a recent report on the mechanics of quorums from the Congressional Research Service.

As to the final part of D.F.'s question, the terms of Cabinet secretaries do not expire when the President's term does. This is why those who remain for two terms do not require re-appointment or re-confirmation by the Senate, and also why there is an expectation that resignation letters will be submitted at the end of a president's second term. If the secretaries' term was automatically ended, there would be no need for the resignations. So, if the Republicans can somehow stop the Electoral College from making a decision, and can somehow stop the Speaker of the House and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate from succeeding to the presidency, then yes, you're looking at President Mike Pompeo.

Again, though, we don't believe this is actually possible. There are too many ways for the Democrats to game the Electoral College in the event of chicanery. And if there is no election, then House Democrats will just change the rules to declare that the Speaker's term does not end with the end of a congressional session (keep in mind, the Speaker need not be a member of Congress). And if House Democrats don't change the rules for the speakership, then Democrats will find a way to choose a Democratic pro tem. And so, we're back where we started: If Donald Trump wants to stay in office, he needs to win the election.

Q: Most predictors' lists of toss-up states include some or all of Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Trump, improbably—and by some slim margins—won all of these states in 2016. In reference to Civil War battles, you gentlemen noted that playing defense is "much easier than playing offense." Do you think that will also be true for Trump in these states in 2020? J.M., Norco, CA

A: Just because playing defense is easier doesn't mean the defense always wins. In the Civil War, the Confederates were defending at Forts Henry and Donelson, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and Murfreesboro, among others, and ended up on the losing end.

Anyhow, let's turn to the data and see what happened in the half-dozen states that the last three presidents (all two-termers) won by the closest margin in their first elections:

| |

|||

| State | 2008 Margin | 2012 Margin | Difference |

| North Carolina | +0.32% | -2.04% | declined by 2.36% |

| Indiana | +1.03% | -10.2% | declined by 11.23% |

| Florida | +2.82% | +0.88% | declined by 1.94% |

| Ohio | +4.59% | +2.98% | declined by 1.61% |

| Virginia | +6.30% | +3.87% | declined by 2.43% |

| Colorado | +8.95% | +5.37% | declined by 3.58% |

| |

|||

| State | 2000 Margin | 2004 Margin | Difference |

| Florida | +.01% | +5.01% | improved by 5.0% |

| New Hampshire | +1.27% | -1.37% | declined by 2.64% |

| Missouri | +3.34% | +7.20% | improved by 3.86% |

| Ohio | +3.51% | +2.11% | declined by 1.4% |

| Nevada | +3.55% | +2.59% | declined by 0.96% |

| Tennessee | +3.86% | +14.27% | improved by 10.41% |

| |

|||

| State | 1992 Margin | 1996 Margin | Difference |

| Georgia | +0.59% | -1.17% | declined by 1.76% |

| New Hampshire | +1.22% | +9.95% | improved by 8.73% |

| Ohio | +1.83% | +6.36% | improved by 4.53% |

| New Jersey | +2.37% | +17.86% | improved by 15.49% |

| Montana | +2.51% | -2.88% | declined by 5.39% |

| Nevada | +2.63% | +1.02% | declined by 1.61% |

And now, let's put all the results together:

| President | Did Better Second Time | Did Worse, but Held | Did Worse, and Lost |

| Barack Obama | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| George W. Bush | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Bill Clinton | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Totals | 6 | 7 | 5 |

This analysis cannot account for factors like demographic changes, differences between opponents, and the greater seriousness of Ross Perot's 1992 bid compared to his 1996 bid. However, you can see that presidents have held on to close states (72.2% of the time) more often than they have lost them, which supports the assertion that defense is easier than offense. However, 72.2% is considerably less than 100%, and Trump can't afford to lose too many close states from 2016 (between one and three, depending on which states they are). Further, one reason that a lot of those holds were holds was that the first-election margin of victory was pretty large. Trump's six closest wins were Michigan (+0.23%), Pennsylvania (+0.72%), Wisconsin (+0.77%), Florida (+1.20%), Arizona (+3.55%), and North Carolina, (+3.66%). That means that states that ended up in the "Did Worse, but Held" column for these other presidents are in danger of ending up in the "Did Worse, and Lost" for him.

Q: I get that vote-by-mail can (and will) increase the number of eligible voters who actually vote. (Contrary to the jokes, all the Gen-Xers, Millennials, etc., who I know do know how to use the US Postal Service). But who counts those votes? You guys, along with all the Democrats, are big supporters of vote-by-mail. But suppose the vote is really close in Florida—maybe the key state this race—and Joe Biden wins by 1,000 votes or so? If the Florida Secretary of State is responsible for the vote count, what are the checks and balances keeping that person (and his/her minions) from "losing" about 2,000 Biden votes to swing it the other way? I know this is possible in any election, but it seems (to me) even more likely in a vote-by-mail election. I haven't seen this issue brought up so far. Is no one concerned about this? K.F.W., El Dorado Hills, CA

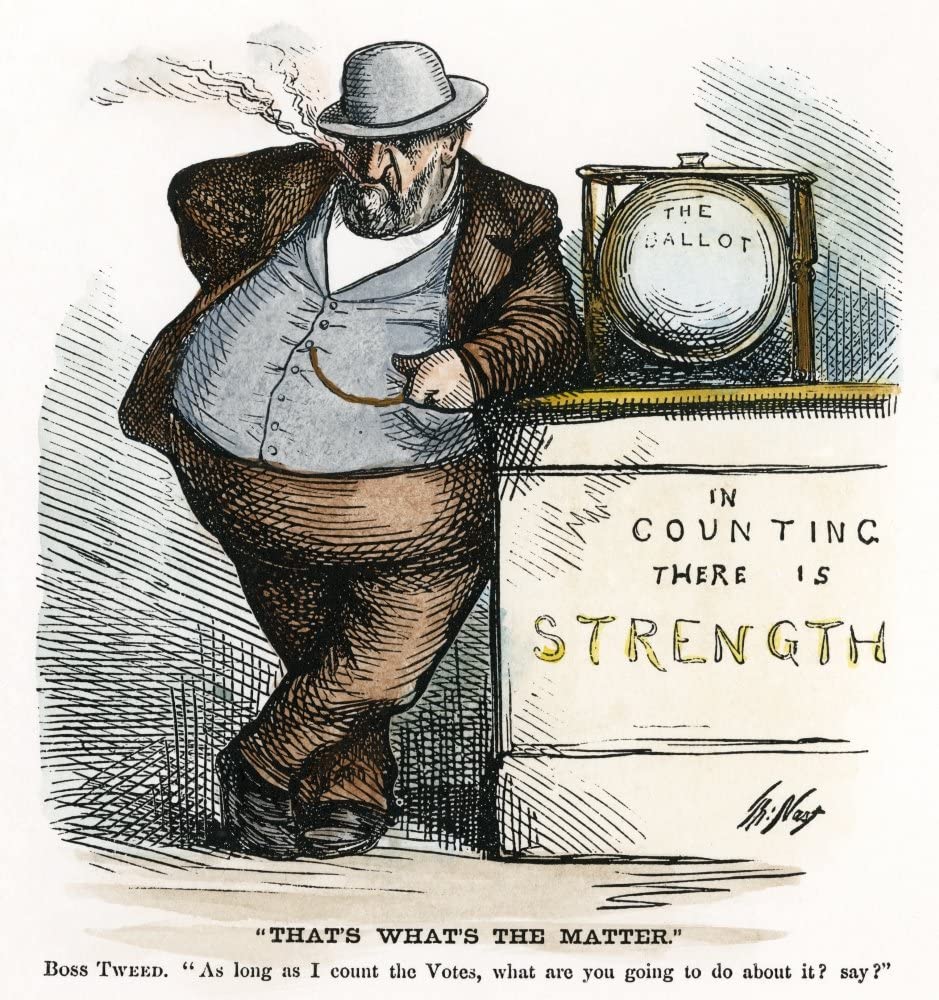

A: We are going to start with this Thomas Nast cartoon from the Gilded Age:

This is a critical commentary on the notorious Gilded Age political boss William Magear Tweed and his well-deserved reputation for cooking the books when it came to election results. In other words, the problem that you identify has been a part of U.S. elections pretty much as long as there have been U.S. elections.

We agree with you that this is a concern and have written as much before. Given that substantial numbers of ballots by mail are going to happen this year (Texas is the latest state where "fear over COVID-19" has been deemed an acceptable reason to ask for an absentee ballot), it is imperative that a process for guaranteeing the integrity of the count be developed. There are two, related reasons for this. The first is that there are a number of states that have, like Boss Tweed, developed a reputation for shenanigans. The second is that in any state where the result is close, or even moderately close, people are going to speculate that something shady took place. The states need to be able to refute such suppositions.

The solution we've advocated is that states adopt a system like the one Washington and Oregon have, wherein the state sends confirmations via text message when your vote is received, and when it is counted. That seems like a big step in the right direction. What is also possible is to have a law or procedure that says when the votes are actually counted, each political party that is on the ballot is entitled to have one person chosen by the party physically present at the counting and is permitted to make a video recording of the proceedings and to publish it.

Q: With the U.S. quickly becoming a banana republic, is it too early to start discussing election monitoring for November? We know our election security is inadequate and the barriers to keep people from voting are multiplying. Has the time come for election monitoring? If so, what would it take? Who makes that decision and organizes it? Who has to sign off on it? Is there anything we can do to help get the process started? Do you think it's necessary or am I overstating the need? S.S., West Hollywood, CA

A: We agree with you that this is a good idea, and it's not unheard of in American history (the Voting Rights Act of 1965, for example, allows the appointment of federal election monitors). However, it is unlikely that Americans would allow monitors from a foreign country, as that would be seen as an affront to the country's sovereignty. Can you imagine what Donald Trump, just by himself, would do with that? And do we really want Russians not only hacking the election but also monitoring the counting?

As to domestic monitors, it's hard for us to think of where to find enough trustworthy ones. There are about 120,000 polling places for a presidential election, and you can't ask one person to do the job, all by themselves, for 1-2 days straight. So, something like a quarter million or a half million monitors would be needed to keep an eye on all polling places. Where would you find that many people who could handle the job, and who can be trusted not to have a hidden political agenda? It would not be easy, even if it does come to pass. Of course, we all know that it's really only necessary to monitor polling places in a few states, but imagine the stink that would be raised if, say, Wisconsin was monitored and Montana wasn't? Yikes.

Anyhow, given the precedent that's already been set by the Voting Rights Act, Congress quite clearly could do this if they so chose. Undoubtedly, it could be done at the state level, but that arrangement falls victim to the Catch-22 that the states that need monitoring the most are the least likely to be interested in honest elections. Add it all up, and we just don't see how it happens.

Q: Might it accomplish anything positive to have GOP representatives in Joe Biden's cabinet? If so, who and what position would you like to see? C.S., Duluth, MN

A: Actually, it's been customary in most recent administrations (the current one excepted) to have at least one member from the other party in the Cabinet. Obama had four over the course of his term: Ray LaHood as Secretary of Transportation, Robert McDonald as Secretary of Veteran's Affairs, and Robert Gates and Chuck Hagel as Secretaries of Defense. George W. Bush had Norman Mineta as Secretary of Transportation, Bill Clinton had William Cohen as Secretary of Defense, and George H.W. Bush and Ronald Reagan both had Lauro Cavazos as Secretary of Education. Obviously there is some value in this in terms of sending a message of bipartisanship (not that it did Obama much good), as well as broadening the potential talent pool.

In terms of a hypothetical Biden cabinet, we don't advocate for candidates for office, but we will say that Biden would undoubtedly choose someone who is an old-guard Republican, and not a Trumpublican. Mitt Romney comes to mind, as does Rep. Justin Amash (I-MI). The most likely thing, however, is that he picks one of his former Senate colleagues that he knows he can work with. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) or the outgoing Lamar Alexander (R-TN) seem the obvious choices.

Q: Since Donald Trump was elected (and perhaps before), it has become apparent that our Constitution needs some updating. While the current political climate does not seem ideal for this actually happening, what Amendments would you add to the Constitution to fix the biggest issues that you see in the country and the government? R.M., Pensacola, FL

A: This could be a long, long list, but we are going to limit ourselves to three. In our view, the most problematic things are the partisan mess the federal court system has become, the dysfunction in the Senate, the undemocratic elements of elections, and the enormous and largely unchecked soft power of the President.

- A judge may serve no more than 10 years as a district judge, no more than 10 years on the courts of

appeals, and no more than 15 years on the Supreme Court. When a judge is nominated for an open court seat,

their nomination must be considered by the Senate in one month or less, and must be approved by 65% of the

senators. If a nominee fails, then they are rendered ineligible for a federal judgeship for no less than two

years, but that minimum drops to 60% for the next candidate, 55% for the third candidate, and 50% for every

candidate thereafter.

- Any Senator may request consideration of a bill. If 25% of the Senate concurs, that bill must be brought

to the floor of the Senate within two weeks.

- The Electoral College is abolished; the presidency will henceforth be awarded by a straight popular vote. Elections will be administered by the federal government, with the FEC setting policy for their conduct. Both state and federal district maps will be drawn by an FEC-appointed regional commission, and must be approved by a panel of three federal judges.

As to the "soft" power of the presidency, that is a real can of worms, but as starters, how about these. The president can declare a national emergency for 30 days, but continuing it beyond that requires consent of both chambers of Congress, which must specify a time limit of no more than 90 days, after which another vote is needed. Congress can also retract its own powers it has given away. For example, only Congress may levy tariffs by law. The president's only role is signing or vetoing tariff bills. Also, a law making it a high crime (as meant by the Constitution) if the president spends any appropriated funds for any purpose other than the one Congress specified by law. Also Congress could take another stab at the Tenure of Office Act and try to reword it to pass muster with the Supreme Court this time. If done during a Democratic presidency, Chief Justice John Roberts might just approve. Another law could say that when a cabinet secretaryship was vacant, the deputy secretary automatically becomes acting secretary. If there is no deputy, then the highest ranking officer in the department who has been Senate confirmed becomes the acting secretary. In an emergency, if no department official has been Senate confirmed, then the president could snatch a Senate confirmed officer from another department, but under no conditions could an acting secretary be anyone who has not been confirmed by the Senate during the term of the president (so Bill Barr couldn't sneak under the wire by virtue of his confirmation in 1991).

If readers would like to submit an amendment they would really like to see, we'll run some of them in the mailbag.

Q: You recently spoke to how the parties evolved over time and you shared a very interesting chart. I remember when people used to argue that both parties were the same. But since then, we have seen the two parties become increasingly polarized. There is a tribalism among party devotees that rivals the worst fans of many sports teams. It is almost as if it has become just about winning and "owning" the other party, just for the sake of the "W" and nothing more. With jungle primaries and the concept of ranked-choice voting catching on in some parts of the country, is it worth asking whether the traditional political parties have outlived their useful purpose? Do we need political parties anymore? What would America look like if there were no more parties—just individual office-seekers and office-holders? And if we must have them, is there any solution to this polarization? K.F., Framingham, MA

Q: You often reference how hyperpartisan the U.S. is today. But when I read about the Democratic-Republicans vs. the Whigs or the slave states vs the free (or even think about events in my memory, like the Iraq War and Clinton's Impeachment), it certainly seems like there have almost always been significant partisan divides in the country. Does now seem genuinely worse, in terms of division, than all of those periods? J.M., Seattle, WA

A: There have been a few times that America has tried to move beyond parties, most obviously in the 1790s and the 1820s. And it turns out that for all their downsides, parties also have benefits, most obviously creating a reliable base of support for a particular political program. For that reason, it is simply inconceivable that the U.S. will ever be truly party free, regardless of how the elections process is changed.

As to polarization, these things tend to go in cycles, and usually happen when a realignment is under way, as it clearly is now. Much of today's polarization is a product of the fact that the Republican Party's political program has become nearly incoherent, largely because they've now got a coalition of interest groups that don't necessarily have much in common (e.g., libertarians and evangelicals, or the captains of industry and the downtrodden workers). It does not help that the world at large is also undergoing tremendous change (globalization, technological change, greater equality for previously marginalized groups, etc.). Under these circumstances, appeals to emotion and villainization of the other party are the only way for the GOP to keep things from flying apart at the seams. The same was true of Democrats right before the Civil War, Democrats in the latter part of the Gilded Age, and Republicans in the 1960s. Presumably, once things settle down, things won't be quite so nasty.

Q: Your summary of the "what if?" of Abraham Lincoln takes me back to my college years.

One of my professors said the best thing that Lincoln did for his legacy was get shot. He obviously admired

Honest Abe, so this wasn't a slight. His argument was that since we all know Lincoln's obvious political

gifts, and that he was literally at the height of his powers with the Civil War just ended, we view him

through the lens of "what if?" when it's likely that, even with his genius, he might not have been able to

steer the nation through Reconstruction. And then we might look at Lincoln as more of a tragic Shakespearean

figure.

And then there's Woodrow Wilson. The same professor said the worst thing our 28th President ever did for

his legacy was not dying when he had his stroke during his fight for the ratification of the Treaty of

Versailles and the League of Nations. If he had done so, maybe the Senate would have agreed to the Treaty,

since it would be for a martyred President.

C.J., Los Angeles, CA

A: It certainly did help Lincoln's memory that he died at the height of his success and his power, being murdered on Good Friday, no less. And the challenges of Reconstruction did help to destroy the reputation of his co-hero in winning the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant. That said, in Lincoln you have very possibly the greatest politician in American history, and in Reconstruction you have very possibly the trickiest challenge in American history (sorry, FDR). There is no way to know, or even to make much of an educated guess, as to how the meeting of those two forces would have worked out.

As to Wilson, we're skeptical that things would have turned out all that differently if he had died. The reason that the nation was plunged into World War II was that Italy, Japan, and Germany came under the leadership of violent, right-wing demagogues. And those men's rise to power was facilitated by the privations of the Great Depression. There's nothing the League of Nations could have done to counter that, any more than the U.N. is able to stop the rise of demagogues and strongmen today. It's possible that Wilson might have forestalled Hitler's ascension if he had somehow persuaded France and the U.K. that reparations payments were a bad idea, but that ship had sailed long before he suffered his stroke.

Q: I seem to recall that Dr. Samuel Mudd got a raw deal by being sent to prison and the phrase "your name is mud" became a pejorative because Mudd just treated John Wilkes Booth's leg, wasn't a conspirator, and probably didn't even know Booth had committed a crime. Am I right about that? G.W., Oxnard, CA

A: All of these things are commonly circulated as fact, but that doesn't make them correct. Mudd later claimed he didn't recognize Booth, but that story is a little hard to swallow, since the doctor had to see well enough to set a broken leg. Hard to believe he could not also see well enough to recognize a familiar face at close range. Booth and Mudd also had similar political viewpoints, and Booth was prone to bragging, not holding his tongue, so he's likely to have run his mouth about what he had just done. And finally, Booth showed up at Mudd's house with the broken leg in the middle of the night, which is rather...unusual. Add it all up, and if Mudd really was unclear as to who he was treating and why, it's because he consciously decided he didn't want to know. And given the likelihood that the doctor did know something (and maybe a lot more than something) then it's not out of line for him to be sent to the slammer for a few years for aiding and abetting a fugitive.

As to the phrase "his name is mud," the word "mud" was slang for "fool" or "idiot" at least as early as 1600, and the exact phrase first appeared in print nearly half a century before Abraham Lincoln was shot, in an 1823 work entitled Slang, a Dictionary of the Turf, the Ring, the Chase. So, it had nothing to do with Mudd.

Q: Your description of the short life of John Wilkes Booth sounds way too unbelievable as a Hollywood script: the protagonist born into "the most famous acting family in America at that time"—known for a style of grossly over-acting, at that—getting his inspiration as an eyewitness to the execution of John Brown, and making his final decision as an eyewitness to Lincoln's last public address, perpetrating the most consequential assassination in American history (with his own theatrical flourishes, not so deftly executed) followed by his escape and a huge manhunt ending with his capture and death in a barn. Every American schoolchild should be shown this movie, but why doesn't it seem to exist? (Z) lives pretty close to Hollywood, and he's a college professor who has this story as part of his core area of expertise, so has he tried to pitch it? P.M., Albany, CA

A: Well, there have been a few documentaries and TV movies on Booth. And there was a Robert Redford-directed film a few years back called The Conspirator, which focused in particular on Mary Surratt. However, it would be tough to fit Booth's story into a traditional Hollywood plot structure.

Dealing with filmmakers on film projects, or potential film projects, is a maddening business. Nearly every university historian in the Los Angeles area has had at least a few encounters of this sort, including (Z). One problem is that the filmmakers wish to endow interesting events with greater significance than they actually had. There was one group that contacted (Z) and wanted to make a film about Operation Pastorius, which was an incident where a bunch of not-so-competent Nazis tried to stage an invasion of New York and New Jersey in 1942. The filmmakers wanted information on how these men were operating on direct orders from Hitler, or how their failure somehow changed the course of World War II. In truth, the Operation had no significance whatsoever; it was just one of those Hail Mary passes that nations attempt amid the chaos of a war. This group told (Z) that they appreciated his time, but wondered if he knew any other historians who might be more suitable for their needs. He resisted the temptation to say: "Sure. Bill O'Reilly."

Another problem with filmmakers is that they don't really want the historian to tell them what is correct, and what is not. They want to do what they want to do, and the historian is expected to give their blessing and say "Yep! Sounds good!" On another occasion, (Z) was invited to a meeting with a producer who really wanted to make a film about Confederate cavalry during the Civil War. The thought process was that they could attract Civil War buffs and also fans of Westerns (because: horses!). This producer asked for a suggestion of a cavalryman who was dashing and heroic and closely associated with the famous Robert E. Lee. That is easy enough, as that is a description of J.E.B. Stuart. The problem, at least from the producer's perspective, came when (Z) pointed out that Stuart died before the war ended. So, the producer asked for a different famous cavalry officer, one who didn't die in the war. (Z) observed that Nathan Bedford Forrest was a famous cavalry officer who survived the war, but that he was not associated with Robert E. Lee, and he couldn't be used anyhow because he was also a vicious racist who massacred black soldiers at Fort Pillow and helped found the KKK after the Civil War. Remarkably, that did not bring the conversation to a close; the producer wanted to know how to frame Forrest's story so as to make him uncontroversial. He did not like to hear: "Um, that is not possible."

Long story short: (Z) stopped taking filmmakers' calls.

Q: I am curious about what process and tools you use to go from the day's proofread copy to having it appear on the website in the morning. M.S., Cupertino, CA

A: Most of the daily work is actually done in text editors (e.g., emacs). Once a day's posting is written and edited, we run a few scripts that are meant to catch misspellings, certain kinds of HTML errors, and duplicated words. The scripts aren't perfect, but they catch a lot of stuff. Then, the actual site is compiled by a master shell script that calls other programs and shell scripts to construct dozens of pages all over the site, including graphs, charts, tables, and more. A fair amount deals with taking files with lines of numbers and making formatted HTML pages from them. Some of it is written in awk (and not only because (V) is friends with its authors, A., W., and K.). The great thing about awk is that it is extremely stable. The last update was about 30 years ago. With modern software, stuff often breaks because some key tool was updated last night and works somewhat differently from the old version. As an aside, (V) wrote a book published last week that was written in troff—which was also last updated maybe 30 years ago. If it ain't broke, don't fix it. In this way, the site is entirely static (i.e., no pages are constructed on the fly when a reader clicks on anything). The only "dynamic" content is the map, which has pop-up boxes using JavaScript. But from the server's point of view, the JavaScript is just a file built by the master shell script at compile time that is linked to the main page and is loaded when the reader's browser asks for it. By being totally static, we have measured that on election night we have been able to handle 2,500 requests per second without breaking into a sweat, and this on a cheap single-core Linux server on a not-terribly-recent piece of hardware. With dynamic content, this would be a heavy lift.

Q: I'm really enjoying the "behind the scenes" looks at your site. I admit I've never paid much attention to the (V)s and (Z)s at the end of the articles, so I decided to take a look back. When I did so, I noticed that on most days all of the articles are written by just one of you. Is that just coincidence? Or do you actually try to trade off day-to-day duties? L.S., Greensboro, NC

A: There have been lengthy periods where we split each day 50/50. However, we decided about a year ago that it worked better for one of us to take the lead each day, and for the other to just edit and fill in the gaps. We generally stick with the same days each week (for example, (V) generally does Monday posts and (Z) generally does Tuesdays), but we do occasionally trade off if one or the other of us is unavailable, or if political events dictate it (for example, if there is a debate—which is a (Z) item—on a night that would normally be a (V) night). And each of us sometimes has an idea and writes an item on the other's day.

Q: How long does putting this site together generally take you? How many readers do you have? And finally, this info is too good to be lost, but it doesn't really seem to fit a book format. What can be done to ensure your insights are available to future historians? J.A., South Salem, NY

A: A pretty good rule of thumb is that it takes about an hour to write every 1,500 words' worth of content, (or to compile and edit every 2,250 words' worth of letters). Our shortest posts tend to check in at around 3,000 words, which means a couple of hours of writing. Our longest check in at around 10,000, which means around six hours of writing. The post that you are reading right now, if you are interested, is right about 10,700 words.

As to readership, it's hard to know for sure, as there aren't highly precise ways of measuring that. However, it's in the tens of thousands normally, gets into the six figures as an election draws near, and approaches seven figures on election nights. The biggest day was election day (and night) 2008, when we had 1.5 million hits, but this required multiple servers. Measuring traffic is much harder than you might realize, partly because all the IPv4 addresses are gone and companies and universities are turning themselves into pretzels to avoid switching to IPv6. In particular, if an organization has a NAT box on the outgoing fiber, to the outside world, all 5,000 employees or 40,000 students have the same IP address viewed from our point of view. So when we count unique IP addresses per day, we may end up counting 200 students as a single person because all of them have a single (outgoing) IP address. From our logs, we saw 33,991 unique IP addresses yesterday, but we can't tell the real number of readers. Every other way of counting has its own problems. It's not easy to get the real number.

As to saving the site for posterity, we haven't crossed that bridge yet. You're right that a book is not especially viable, because of the volume we produce. Fortunately, it would not be too hard to extract all the text and save it as some sort of online archive.

Q: I have long wondered about the role (or lack thereof) that your departments and institutions play in your work here—and what they get out of it. In the beginning, it seemed like an interesting "after hours" project by an academic who may have chosen to publish anonymously because he did not want his institution to know he was out there doing this, and/or because his institution did not want him out there advertising himself. But over the years, the volume, analysis, and infrastructure of the project have grown to a point that it seems you must have institutional/departmental support, even though you continue to eschew the personal attention-mongering that your more egotistical counterparts (looking at you, Nate Silver) engage in. That also means your employers still earn no public kudos, marketing benefits, nor academic cites from your valuable work. So how and why do they sustain it, if they do? And how and why do you do it, if they don't? J.E.S., Des Moines, IA

A: Academic departments tend to be very conservative. Not politically, but conceptually and methodologically. They struggle to make sense of anything that differs from "the way it's always been done." So, if a person gets grants and publishes books (which V has done plenty of) or if they edit books and publish articles (which Z has done plenty of), then that "makes sense" to academics and also brings glory to academic departments. Something like this site doesn't compute all that well, even if it reaches a hundredfold the number of people that an academic treatise would reach. To put that another way, even in 2020, this site is basically just a curiosity to our colleagues.

That said, we each have job security to the point that the opinion of our colleagues is a curiosity to us. They may not celebrate the site, generally speaking, but they can't stop us from doing it. There are many different hats that an academic might wear, and different academics value those hats differently. Both (V) and (Z) take seriously the hats of "public intellectual" and "teacher," especially the latter, and we see the site as a fulfillment of those roles.

So, there is no institutional support at all. We use our own computers at home to the do the work, and the server is a machine we rent at HostRocket's datacenter near Albany, NY. As an aside, the orginal purpose of the site was to encourage Americans abroad to register to vote by absentee ballot (hence the banner ad at the top of the page, which is probably in need of some updating). It is estimated that 9 million Americans live abroad, which would rank 11th if it were a state, ahead of New Jersey, Virginia, Washington, Arizona, and Massachusetts. Since it is impossible for anyone to go door to door to find them all, (V) thought of the idea of starting a political website to attract their attention by providing something no one else had then—a daily score of the electoral vote (something we will start again this year). The banner ad on top leads them to votefromabroad.org, which is a nonpartisan website that helps voters produce a PDF file they can print, sign, and send to the relevant election administrator to request an absentee ballot.

Back to the main page