Previous | Next

Saturday Q&A

COVID-19, history, and behind-the-scenes questions, just like last week.

Q: I'm wondering if blocking USPS funding could be a back door to eliminating/postponing/kneecapping turnout for the general election? You can't vote by mail if there's no mail. S.K., Los Angeles, CA

Q: When are you guy going to face reality? Unless the election is a total blowout in favor of Biden, then on January 21, 2021, Donald Trump will still be president. He and his cronies will use every dirty trick. Voter suppression, reduced polling places, fear, intimidation, lies and unlawful behavior. If he loses and it's close, he will file lawsuits. Then get it before the Supreme Court. Guess what happens then? J.P., Bronx, NY

A: There are, in the end, five ways that Donald Trump might try to stay in office beyond January 20, 2021:

- Actually win the election: We all agree this would do the job. Obviously, both questioners

are skeptical this will happen. And Donald Trump and his campaign may come to share this skepticism, particularly

if the polls are looking bad in September or October. In that case, he might move on to the various forms of chicanery

covered by the other four items on this list.

- Stop the elections from being held: It will not be easy to get states with Democratic

governors, or with not-Trump-friendly Republican governors (VT, OH, MA, MD) to play along with this. The scenario

contemplated by S.K. is at least plausible, but not very—we can imagine mayors putting "submit-your-ballot"

mailboxes in high-traffic locations, or arranging for UPS or FedEx to collect ballots. And beyond that, if there is no

election (however that might be accomplished), the key is this: Donald Trump's first term ends at noon on Jan. 21, 2021.

End of story. If there's no election, then he will not have qualified for another term, nor will his running mate. It is

also likely (although not certain) that the post of Speaker of the House will be vacant. If the Speakership is

not vacant and Nancy Pelois (D-CA) is still speaker, she becomes the president. If the Speakership is vacant, then the presidency

devolves upon the president pro tempore of the Senate, who will be chosen by a majority of the 33 Democrats, 30

Republicans, and 2 independents who remain in office. Those folks will choose a Democrat as pro tempore by a vote of

35-30.

- Game the Electoral College: The general idea here is that Trump would ask some of his

gubernatorial friends/lackeys to cancel their state elections so as to keep anyone from taking an electoral majority,

thus throwing the election to the House or to the Senate for resolution, where it would be awarded to the Donald by his

Republican allies. We have covered the various scenarios

here

and

here,

and they all end with the same conclusion: There is no scheme that ends with Trump getting a second term; there are too

many counter-moves available for the Democrats, particularly at the Electoral College level.

- Muddy the results, and then get the courts to step in: This is the scenario envisioned by

J.P., and it's the only one on this list, besides #1, that we believe could actually come to pass. But it's not terribly

likely. First of all, Joe Biden would have to win a small number of states (one, two, maybe three) by a slim

number of votes (less than 25,000). Second, there would have to be some plausible argument as to why the final result is

not legitimate. It's true that the current Supreme Court is pretty clearly in the bag for the Republicans when it comes

to elections, but it's also true that they can't just overturn a bunch of states' election results because Team Trump

cooks up a conspiracy theory about undocumented immigrants voting. Keep in mind, the power of the Supreme Court (and,

for that matter, the presidency), rests on the consent of the governed. Right now, a huge percentage of the governed are

very unhappy, but they are still (largely) playing along because they still buy in to the system, if not into the people

who currently run the system. If the President and the Supreme Court distort the system beyond recognition, then that

buy in goes away, and the power of those offices is badly damaged (or even destroyed).

- Stage a coup: Even if Trump were to declare martial law, that does not suspend the

Constitution, and thus does not change the deadline for the end of his first term. That means that if he tries to stay

in office without benefit of having been reelected, he will have staged a coup. Obviously, coups happen, so this is not

impossible. However, this approach would require buy-in from federal law enforcement and from the military. You will

notice that nearly all successful coups involve military officers, or else civilian leaders who had seeded the upper

ranks of the military with their close personal allies. Neither of these things is true of Trump, and our experience is

that America's soldiers take their oaths to defend the Constitution (not the President, take note) very, very

seriously. And even if the President and a cabal of soldiers and law enforcement officers do try to seize extralegal

power, then they will have a rebellion of tens of millions of people to put down.

And, by the way, can we really expect all of this from a president who is more than willing to talk a big talk, but is rarely willing to walk a big walk. When push comes to shove, doesn't he nearly always back down? Can we really believe he has the spine to go full Augusto Pinochet or Idi Amin?

And so, our conclusion remains the same: If Trump wants to stay in office, he better win the Electoral College unambiguously. Any other path ranges from "highly unlikely" to "impossible" on the spectrum of possibilities.

Q: As you and others have talked about in the last couple of weeks, Democrats are pushing for a nationwide mail-in voting system as part of the COVID-19 Relief Bill v4.0. Clearly, Republicans don't want this as they would lose a lot of elections going forward, as you have also talked about. However, let's say this gets enacted. What do you think Republicans' overall reaction would be at that point? Would they continue their drift further to the right, or would they quickly become more moderate in an attempt to remain relevant? R.M., Pensacola, FL

A: This year, there would only be two strategies at their disposal, as we see it: (1) Do everything possible to make it harder to vote by mail, and (2) Do everything possible to call into question the veracity of vote-by-mail, and the eventual results that vote-by-mail generates. There is no plausible way for a party to reinvent itself on such a short timeline, especially when its candidate is Donald Trump.

Long term, if vote-by-mail becomes more common (or becomes the standard), then yes, the Republicans very likely will become more moderate. But that's actually going to happen even if the voting system isn't changed by COVID-19. At the moment, the Republicans are a minority party that has won the popular vote in just one of the last six presidential elections, and that has taken maximal advantage of the system (gerrymanders, stacking the judiciary, the Electoral College, etc.) to maintain influence. However, the demographics that the Party counts on for votes and money (seniors, evangelicals, social conservatives, etc.) are almost all shrinking. The time is coming when they just won't have enough support, outside of a few Southern and mountain states, to stay in power, messing with the system or no. They've got to bring new demographics into the tent, whether a much larger number of Latinos (which would mean changing the Party's position on immigration), or a much larger number of young voters (who don't much care for aggressive anti-gay, or anti-minority rhetoric, or the Party's stance on global warming), or recapturing suburban women (no more toxic masculinity, and no more obsessing over Roe v. Wade). Whatever path is chosen, it's going to be a more centrist one.

Q: You've written previously about how presidential candidates often chose their running mates in order to win the Electoral College in an important swing state, but is there any precedent for choosing a running mate to help win downballot races, like Senate seats? In other words, do you think the two crucial Senate seats up for grabs in Georgia this year will be a strategic point in favor of Biden choosing Stacey Abrams for VP? C.A., Tucker, GA

A: If there is a clear case of picking a running mate with an eye toward the Senate, we certainly don't know about it. And really, it wouldn't have made much sense in past decades. Not only do you need at least one seat that is up in the VP's home state (which would have to be purple) in an election year, there would have to be a reason to think that Senate seat would likely tip the balance of the upper chamber. In past generations, the Senate was often under the complete control of one party, with that party having a margin of 10-20 votes. Even when that was not true, party discipline was not so rigid, and it was common for a few members of each party (or more) to cross the aisle on any particular issue. That's another circumstance where having one extra senator didn't matter that much.

This year, however, we find ourselves in an unusual situation. First, the Senate is so polarized, and party discipline is so rigid, that one or two seats absolutely could be the difference between getting lots done and getting nothing done. Second, we have a purplish state, in Georgia, that has not just one, but two seats up. And both of those seats are held by the opposition. We absolutely think this is an argument in Abrams' favor. Whether it is a definitive argument in her favor is something that only Joe Biden knows, of course. After all, many of the other potential veep candidates also have something to bring in. Just to name one, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D-MI) would almost certainly bring in a key swing state.

Q: Is the COVID-19 money just cash, or a loan against next year's tax return? Is it taxable income? And when they say $75,000 and under, are they talking adjusted gross income (AGI)? E.S., Maine, NY

A: The money is what is known as a refundable tax credit, though one being granted a year early. If the government gives a tax credit, then it's a discount on your tax bill, but one that ends once your tax bill reaches $0. In other words, if you get a $1,000 tax credit, but you only have a $700 tax bill, then the extra $300 disappears. On the other hand, with a refundable tax credit, like this one, you get paid the overage. So, if you get a $1,000 refundable tax credit, but you only have a $700 tax bill, then you get a $300 check from the government.

Anyhow, this payment will not affect next year's tax return at all, and everyone will get the same refund (or will pay the same amount) as they otherwise would have. The payment doesn't even count as income, and so is not itself taxable. The reason it's linked to tax returns at all is that it makes the bookkeeping easier, particularly in terms of making sure that dependent children are accounted for, and also that high-income folks are not overpaid. And yes, it will be based on AGI.

Q: Are there any other states, other than Wisconsin, that have either local or statewide elections taking place at the same time as the primaries, and that have been rescheduled due to COVID-19? The argument I've seen against Wisconsin delaying the elections was that elective positions would go unfulfilled or elected officials would be serving past their term, unlike other states that have pushed the elections back since they are only pushing back the primaries themselves. F.A., Superior, WI

A: Yes. There are many, many cases of localities that have rescheduled one or more elections, and there are at least two states that rescheduled general elections: Texas (from May 2 to July 14) and Missouri (from June 2 to August 4). Because people die, get sick, resign unexpectedly, etc., there are always contingency plans in place to fill jobs that simply cannot remain vacant, all the way from city dogcatcher up to President of the United States. Keep in mind also that elected officials do not generally take office the day after they elected; there's usually some lag time. And so, the argument that Wisconsin simply could not wait is not a very good one.

Q: You guys described the total dysfunction of the Wisconsin primary and the chaos surrounding the events immediately leading up to Election day. Can you please clarify the role played by Gov. Tony Evers (D) in this fiasco? It seems his waffling and lack of decisiveness may have cost the Democrats in this case. I am not in any way excusing the clearly partisan role of the state's GOP-dominated legislature, nor the conservative state supreme court, nor the inevitable 5-4 SCOTUS ruling. But what responsibility does Evers share in the unfolding of this debacle? Does he share some of the blame here? R.H., Anchorage, AK

A: There is no question that Evers stuck to his guns on the original date until very late in the process, and that his preferred solution was to encourage anyone and everyone to vote absentee. We called him out for this (see here for an example), and concluded that he was just a politician playing 3-D chess and ignoring justifiable criticism.

Perhaps we were right to question Evers' motivations, and to wonder if he was guilty of tunnel vision. On the other hand, given what we know now, maybe we were in error. Maybe he looked at a legislative and a judicial branch controlled by Republicans, knew there was no chance they would work with him, and he tried (without much success) to make the best of a bad situation. Put another way, he seems to have exercised all the options available to him—pushing for more support/time for vote-by-mail, going to federal court, attempting to postpone the election by fiat—and none of them actually worked out. If he had it to do all over again, it's hard to see what he might have done differently, besides maybe getting started earlier on advocating for vote-by-mail.

Q: I have always divided the U.S. into North vs South when it comes to a state's culture. But I cannot understand the "Cheese Culture," for lack of a more amusing name for it, of Wisconsin. It seems very "Southern," but where did that come from? As a Midwestern State, I would expect it to be more like Pennsylvania than North Carolina. What makes it, in its voter-suppression-behavior, so much more Southern? C.P., Lancaster, PA

A: Actually, we think that while the end results may be the same, Wisconsin is not all that similar to Southern states. For going on two centuries, political power in the South has been maintained by virtue of one-party rule and, to a greater or lesser extent (depending on the era), white supremacy. White Southerners learned that, once you open the door a little bit when it comes to sharing power, you risk the possibility of the door being kicked open all the way. This is why places like Alabama and Arkansas, who are among the reddest states in the nation, nonetheless have voter ID laws.

Wisconsin, in contrast to the Southern states, is not red at all. It's about as purple as it gets. And what happened is that, a little over a decade ago, the Republican Party noticed that the Democratic Party was neglecting downballot races. So, the red team made a concerted effort to fill state legislatures (particularly in purple states) with Republicans, knowing that they could (and would) control the post-2010 census redistricting process, and could gerrymander things to the Party's advantage. At the same time, Republicans in general, and Wisconsin Republicans in particular, got very assertive about filling judicial posts with conservative judges. There was a time when the Wisconsin Supreme Court really was nonpartisan, but that time came to an end with the seat that came up for election in 2011, when the GOP moved heaven and earth to keep arch-conservative David Prosser Jr.'s seat for him. The Court's elections have been hyperpartisan ever since.

In short, the Southern scheme for maintaining power has been around since long before any of us were born. The Wisconsin scheme, by contrast, is of recent vintage, and may not survive past the next census.

Q: One thing I haven't seen mentioned is the temporal connection between the Wisconsin primary and Sen. Bernie Sanders' (I-VT) withdrawal the day after. As the results from Wisconsin won't be in for another week, nothing that could have happened in that primary could have affected Sanders' thinking. However, as you've written, there was a hotly contested, highly partisan state Supreme Court race the same day. By staying in through Wisconsin, Sanders likely boosted Democratic turn-out because the presidential primary still meant something to Democratic voters. It would not surprise me at all if one of the things the Sanders and Biden campaigns discussed over the past few weeks was Sanders staying in to help the Democrats in Wisconsin. If so, it bodes very well for Biden-Sanders cooperation through the general election. R.M., Brooklyn, NY

A: Your theory is certainly possible. Neither Biden nor Sanders would admit it, at least not right now, since that sort of scheming would not be a good look. We'll have to wait for their autobiographies, Eat Pray Gaffe and I Never Quite Figured Out Why the Caged Bird Sings.

Another possibility is that Sanders has been granted some sort of concessions in exchange for dropping out. Again, this is not likely to be revealed anytime soon if it is the case, but it is already known that Barack Obama spoke to Sanders on the phone multiple times before the Senator dropped out. Maybe he was granted influence over the Cabinet, or some judicial picks, or the platform. Or perhaps he was granted some other request. For example, we were about to write an item suggesting that if Sanders really wants to be president, his best option would be to drop out in exchange for a promise that he'll be the nominee if Biden falls ill. Maybe a deal like that was struck?

A third possibility is that Sanders and his team took the lay of the land, and came to the conclusion that the time and energy, and risk to the Senator, his staff, and the voters, just wasn't worth it. Undoubtedly, they all worked very hard on this campaign, and invested a lot of blood, sweat, and tears in it. Although the writing was on the wall four weeks ago, perhaps Sanders & Co. needed to go through some version of the five stages of grief before they could accept that the end had come.

Of course, it could also be multiple things off this list, or even all of them.

Q: I've see multiple mentions of COVID-19 outcomes being worse in patients with underlying health issues and in persons of color, but I am curious why there is no mention of the increased risks in people who smoke cigarettes or vape? Behavioral modification should be the first step in most therapeutic interventions, not to mention the increased risk of acquiring the virus that comes from going out and restocking one's dwindling supply of coffin nails. B.B., St. Louis, MO

Q: In your item "COVID-19 Doesn't Discriminate, Except When It Does," I wonder why did you not also mention that COVID-19 disproportionately kills men over women, despite an already-two-months-old published study on the subject, and widely confirmed since then? That does not fit the "narrative"? N.T., Dallas, TX

A: When doing this sort of writing, one has to balance the desire to be thorough with the need to be clear and not too wordy. As to smoking, we cannot really speak for other writers, though we've seen items about the link between smoking (tobacco, marijuana, vape) and COVID-19 from quite a few outlets, including CNN, The New York Times, Fox News, and Scientific American. For our part, we write about politics, and in particular elections. There are many groups that are disproportionately affected by COVID-19, and that have a clear political lean, one direction or the other (older people, urban dwellers, black people). However, we do not know what the lean of smokers is. Our guess is that tobacco smokers learn Republican and vapers/pot smokers lean Democratic, but that's just a guess. Anyhow, our lack of clarity on that point means we can't really connect COVID-19, smoking, and politics in any useful way.

As to men, certainly they are an identifiable demographic, with a bit of a political lean. And we've written about COVID-19's impact on them, at least a little (see here, for an example). However, the piece you are asking about was about race, and in particular COVID-19's impact on black Americans. Talking about men vs. women would have been off topic; that's just not what the piece was about. So, if that's what you mean by "does not fit the narrative," then sure. However, the phrase "does not fit the narrative" generally implies that we deliberately withheld or skewed information in service of our political agenda. We honestly cannot figure out what "narrative" we might be advancing here that is somehow served by deliberately omitting the disease's impact on men.

Q: What would it take for a 50-state-plus-DC blowout of Trump (or something close to that)? Is there even a scenario where this is a possibility (say, the Second Great Depression)? These unemployment numbers are staggering, which suggests at least some possibility of this. What conditions make a blowout more likely? I still don't really understand the 1972 election and, especially, the 1984 election. E.W., Skaneateles, NY

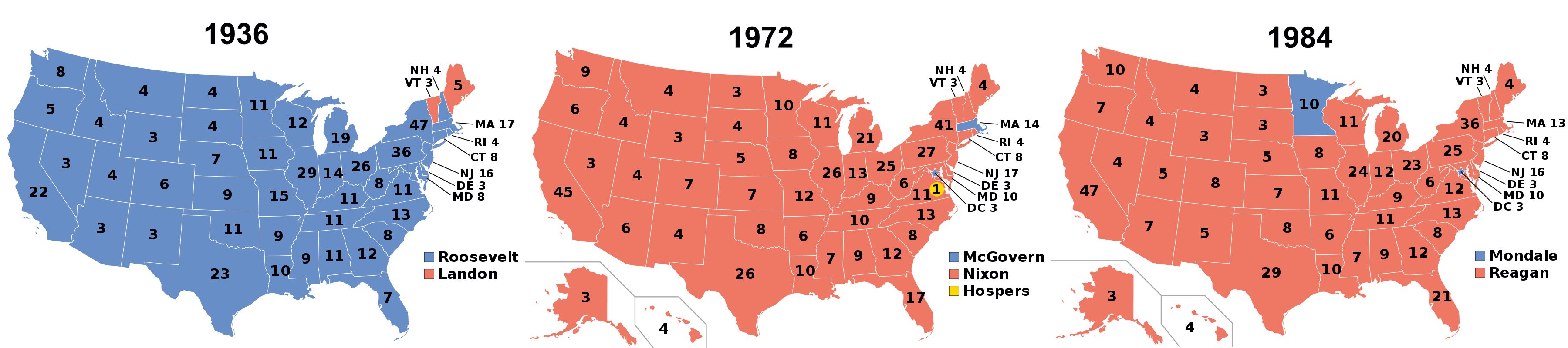

A: Doubtful. First of all, here are the three biggest Electoral College blowouts of the last century:

Notice that all three were presidents who had enjoyed productive first terms, and were standing for reelection. Since elections like these tend to be referendums on the incumbent, and since the nation wasn't as polarized in those decades as it is today, it was plausible for an effective president to win a lot of crossover votes and to give his opponent a drubbing, particularly if their opponent was unexciting. And whatever terms have been applied to Alf Landon, George McGovern, and Walter Mondale, "exciting" has not often been among them. Anyhow, given that Biden is not an incumbent running on the strength of a strong first term, he's not in the position that it generally takes to produce a near-sweep like these.

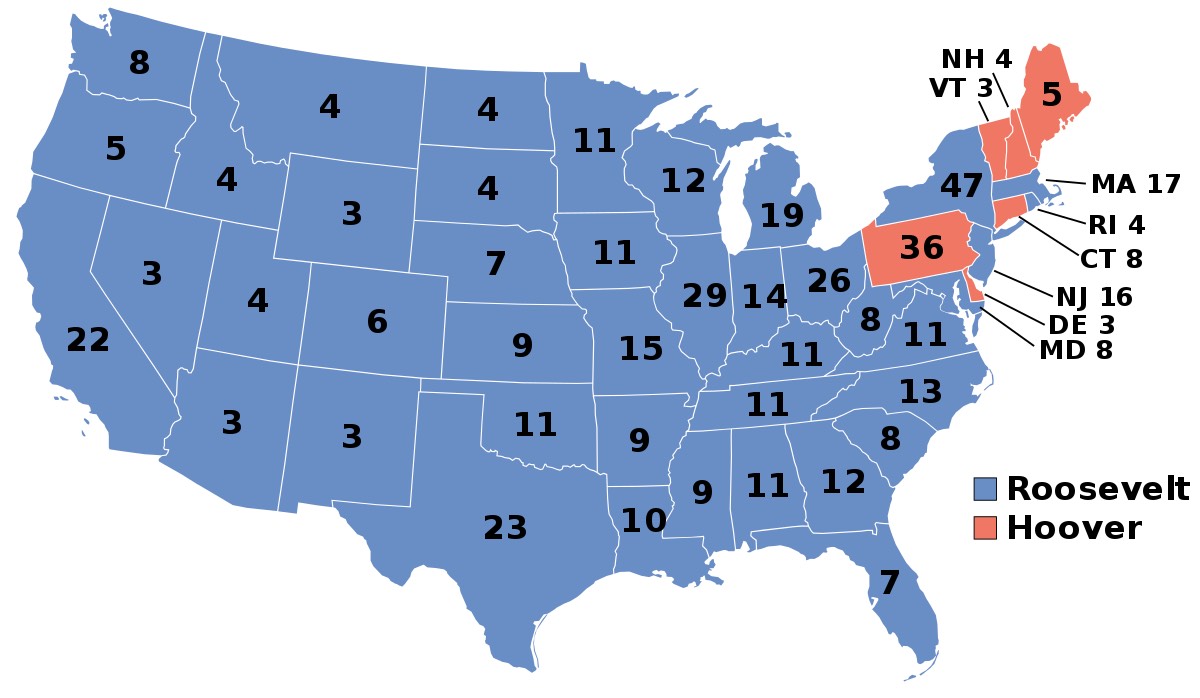

Now, it is true that people were so angry with Herbert Hoover that FDR's first election was also pretty lopsided:

That is the scenario that Biden would be hoping for—a "Second Great Depression," as you note. However, 1932 was a realigning election, whereas in 2020 Americans are highly polarized, and even if Biden makes inroads with suburban women and wins back white, working-class men, it's difficult to see how he could plausibly welcome more new (or returning) voters into the tent than FDR did.

Also important, and obviously highly related, is that it's entirely possible to live in a conservative or liberal "bubble" these days. Back in the 1930s (and the 1970s and 1980s), every voter got pretty broad exposure to each candidate's strengths and their campaign pitch. At the same time, it was pretty hard to circulate outright lies and falsehoods about the opposition and have them stick (not impossible, mind you, but pretty hard). Today, it is just too easy to feed people in red-leaning states a steady supply of negativity (including, very possibly, lies) about a Democrat, while largely shielding them from the positives. In that way, it's like the election of 1860, when—as we mentioned recently—Abraham Lincoln wasn't even on the ballot in Southern states. And so, no matter how bad things get for Trump, it's just hard to see how Biden could plausibly win an Oklahoma, or an Idaho, or a Mississippi.

Q: Even prior to COVID-19, there was reason to fear that the Trump administration had zero intention of completing a fair and accurate census. Now that COVID-19 would provide ample cover for any chicanery (particularly for an administration willing to engage in chicanery right out in the open), I'm wondering if there's an historical precedent for this. More specifically, has there ever been a census that we knew, either at the time or later, was grossly inaccurate? If so, what was the fallout from it in the following ten years? A.W., Chicago, IL

A: The two major problems that arise in censuses are undercounting (people who get missed entirely) and overcounting (people who accidentally get counted twice). Undercounting is always a bigger problem, though the ratio of undercount to overcount used to be around 2-to-1 (that is to say, for every person who got double-counted, there would be two people missed). These days, overcounting has been all but eliminated, while much less progress has been made on undercounting. In 2010, it's estimated that there were a mere 36,000 people who were double-counted, while more than 10 million went uncounted.

The most notoriously inaccurate census was in 1940, which they quickly discovered—by accident—was way off. If you think about it, you may be able to figure out exactly what led to this accidental discovery; we'll tell you in the next paragraph. The 1970s census was also wonky; it was particularly inaccurate in cities and in minority neighborhoods. This produced a significant undercount of black citizens, and triggered congressional hearings led by Rep. John Dingell of Michigan. At that point, he had only been in office "seemingly forever" as opposed to "apparently since the beginning of time."

Anyhow, the way that they figured out that the 1940s census was way off target is that it was completed in mid-1941. And around that time, American men were once again required to register for the draft, as President Roosevelt suspected that his ongoing negotiations with Japan would not turn out well. And the number of young men who registered was way, way more than the number of young men who lived in the whole country, according to the census. Oops! This caused the government to take a long look at their process, and to improve it in several ways. Most obviously, they got serious about two types of post-census double-checks that have been undertaken for every census since then. The first of these is that the Census Bureau compares their final numbers to other counts of the citizenry (for example, drivers' licenses issued), to make sure that there are no obvious discrepancies. The second is that they re-survey certain narrowly selected areas very closely, and compare the numbers to what they came up from their broader, less-close enumeration. That's how they calculate (pretty) precise undercounts and overcounts.

Generally speaking, the main impact of a badly executed census is...they try really hard to do better the next time. It's also possible that known errors could lead Congress to grant some sort of special, vaguely corrective funding (for example, in the 1970s, Dingell argued for more funding for housing projects than the census figures might otherwise indicate). There is no precedent for doing a "re-census," nor any for tweaking the decade's apportionment of Congressional seats, once it's set. It's at least possible that if the Trump administration really botches things, and that becomes apparent, the Congress could call for a new census. The Constitution says they have to be held at least once every ten years, but doesn't forbid them from being more frequent than that. It's not likely, but it's possible.

Q: The John Brown discussion reminded me that you had mentioned before that in many ways our current political arguments are just continuations of battles we were fighting during the Civil War. Perhaps I missed it, but could you recommend specific reading that makes this case? D.H., Marysville, WA

A: Conveniently, there is a new, and very good book on this subject that just came out a week ago. It's Heather Cox Richardson's How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America. The book traces modern conservative ideology from the Old South, to the Wild West, up through the present day. Richardson's one of the best historians working today, and (Z) has heard a couple of talks from her based on chapters from the book. You're not likely to find a better reading on the question you raised.

Q: When I visited Harpers Ferry, I recall hearing that John Brown actually had a rifle shot lined up on Col. Robert E. Lee, but didn't fire. Is that just true or just a legend? If true, who do you speculate would've risen to command the Confederate Army, had Lee been killed at Harper's Ferry? (By the way, the view Jefferson saw is beautiful, but I think Teddy Roosevelt probably saw even more dynamic scenes in the western states of our country. S.B., New Castle, DE

A: You're close. Jesse Graham was one of the hostages taken when John Brown's men seized the armory. According to Graham, one of Brown's followers, whose name was Edwin Coppock, had a bead on Lee and Graham persuaded him not to take the shot.

As to what would have happened if Lee died on that day, we will first point out that Lee only commanded the entire Confederate Army for a couple of months, at the very end of the war, by which time it did not matter. For most of the war, he only commanded the Confederacy's most important army, the Army of Northern Virginia. This resistance to centralized command, which was not shared by the Union, was an aspect of the Confederates' general preference for states' rights. That means that, assuming that Lee died in 1859, then the person to replace him would, of necessity, have to be a Virginian. It would not be viable to have a Georgian (James Longstreet) or a North Carolinian (Braxton Bragg) commanding that particular army.

With that established, the obvious answer to your question is Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who actually commanded the ANV before Lee did, and only yielded the command due to being injured at the Seven Days' Battles. If Lee had not Wally Pipped him, then Johnston presumably would have resumed command after recovering from his injuries. If not Johnston, it's hard to think of a Virginia general who might have filled that role. Stonewall Jackson was not well suited to overall command, Jubal Early took too many dangerous risks, and George Pickett was basically incompetent. Maybe Richard Ewell, although it's hard to think that someone whose men called him "Old Bald Head" would inspire anything close to the devotion that Lee did.

As to the views, we will let people decide for themselves:

The shot above is the view from Jefferson's Rock. The shot below is the badlands, where TR spent most of his time in the West.

Q: I'd like to hear details about how you handle the geographical distance between yourselves. Do you ever meet in person? How often do you converse remotely? Morning arrives about 5 hours earlier for V than it does for Eastern Time Zone residents. Is there any advantage to that? Disadvantage? I would find it very interesting if you were to just describe a typical day, including some of these details. M.R., New Brighton, MN

A: Let's use a Monday posting for our example. For a Monday, (V) finishes any contributions he's going to make for the day by about 7:00 p.m. ET Sunday. Then, (Z) tends to begin work around 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. ET Monday, reading over and editing any of (V)'s material (and sometimes adding to it), as well as adding his own material. Once (Z) is done, (V) reads things over (and sometimes adds stuff), and then we try to post by 6:00 a.m. ET Monday. We don't always make it, especially on the weekends, but we try. The primary benefits facilitated by the time zone differences, as well as the fact that (Z) is a night owl, is that when we do post, the information tends to be the very latest, no more than 30-45 minutes out of date. And many times, some piece of news has broken just as the day is getting started on the East Coast, and just as we're about to post, and we've been able to adapt to it in real time.

As you may have noticed, we each have our areas of specialty; (V) is the expert on polling and anything mathematical, as well as election security, among other things. (Z) is the expert in history, and in anything that ties into sports or pop culture, among other things. However, the time difference also shapes what we write. Because he works earlier in the news day, (V) is more likely to write not-really-time-specific, big-picture items, like "Biden may have an easier time unifying the Democrats than Clinton" or "Here are some unexpected effects of the pandemic." On the other hand, because he works later in the news day, (Z) writes the vast majority of items on debates and on election results.

The vast majority of our communication is via e-mail; we do cross paths in person about once a year, normally when (V) travels to California for a conference.

Q: I've been a loyal reader of your site since 2004. After each presidential and midterm election, once everything was settled, the site "went dark" for another year or so, only posting sporadic updates. In 2017, sometime after Trump was inaugurated, you announced that the site would "go dark" again and stop publishing daily updates. Yet this never happened, and you've remained a daily politics blog for the last three years. I've certainly appreciated reading the site daily since then, but my question is: why did you change your minds and choose to keep publishing daily outside of election season? F.M., Charlottesville, VA

A: There are three reasons, we would say. The first is that Donald Trump and his band of merry men generate far more news than any normal president would. The second is that (Z) joined the site, and two people splitting the work are less likely to burn out than one person doing 100% of the work. The third is that we added this Q&A feature, and the mailbag feature, and those things turn out to work best on the weekends. And so, the only cutback we actually made was to take weekends off, and that only lasted a month or two before we added the new features.

Q: What's the backstory behind (Z) joining? Did he volunteer? Was he recruited? Or did he complain about something on the site, and when the response was "If you think you can do better ..." he accepted the challenge? And who are your support staff, if any? S.C., Mountain View, CA

A: (Z) was a regular reader for many years, and so saw the same "this site is going dark, and may or may not come back" messages as everyone else. After the 2014 cycle, he e-mailed (V) and offered to join the site as a co-author. There was no answer. Then, a few months later, it occurred to (Z) that the E-V e-mail address (which was then a yahoo address) was flooded, and that his message probably never got read. So, he tracked down (V)'s university address, and got a quick response. After a few weeks' conversations, and (Z) writing a few test items (most obviously, the pros and cons lists for the 2016 Republican presidential candidates), it was a go.

Beyond the two of us, there are a handful of folks who help with technical matters, like keeping the servers configured properly, and a person who generously volunteers her time to put in the polling numbers when we start updating the map above. We also have seven people who have kindly agreed to be our regular copy editors, and to e-mail us daily (or almost daily) with errors, so we can fix them. While we don't want to name them, in case they would prefer not to be identified, we can say thanks to S.K., L.H., E.D., M.B., R.P., D.R., and B.H.!

That's the whole team, and we are grateful for the assistance of all of them.

Q: Love your website, and have been reading it since the early days, but I'm wondering why the answers to readers' questions aren't signed (V) or (Z) or (V & Z) like the news features and analyses are? Do the professors write the responses, or are they handled by interns and staffers? H.F., Pittsburgh, PA

A: The reason that we do not sign the answers to questions is that we found it to be distracting, visually. For several reasons, most importantly that we want to be able to respond to last-minute developments (and questions) as discussed above, (Z) selects most of the questions and writes most of the answers, and then (V) goes through and adds anything he thinks is useful or interesting.

Also, we are often asked if some portion of the site is written/prepared by grad students or research assistants, or anyone else. The answer is no. Every word is written by one of the two of us. The only possible exception to that, at least at the moment, is that sometimes one of the copy editors will suggest a better wording for something than what we used. In that case, you could plausibly argue that the editor wrote 0.2% or 0.3% of that day's posting. That said, we are planning to begin accepting guest contributions; more on that to come later.

If and when we do get another contributor, or guest contributors, those folks will be properly credited. It is true that, in academia, scholars sometimes have student co-authors. It is also true, however, that it would be unethical to use them and not credit them.

Back to the main page