Previous | Next

Wisconsin Soap Opera Takes Many Twists and Turns

In theory, Wisconsin is supposed to be holding its primary today. In practice, the current COVID-19 pandemic makes that very problematic. In the end, a number of Republican judges and politicians saw to it that the primary will effectively go forward as planned.

Until just a few days ago, Gov. Tony Evers (D) also wanted the elections to go forward as planned, though with heavy reliance on voting by mail. The state's Republican-controlled legislature was not interested in facilitating this, and there was a bit of a public squabble that seemed to be resolved when a federal judge refused to postpone the election, but did grant an extension for the vote-by-mail ballots, declaring that they merely had to be in the mail by Apr. 13 in order to be counted.

In the last 72 hours or so, though, this equilibrium was upset by much movement on both sides of the argument. Evers threatened to postpone the election by fiat (on Friday), then backed down when the legislature told him to shove it (Saturday), and then decided to postpone by fiat after all (Monday morning). The Wisconsin GOP promptly filed suit with the state's supreme court. Somehow, the justices managed to hear the case, and to issue a ruling within just a few hours. Voting entirely along party lines, 4-2, they quashed Evers' order.

Concurrently, Wisconsin Republicans also petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to get the deadline for vote-by-mail ballots reset back to Apr. 7, the original date. Monday evening, the Court ruled 5-4 (also along party lines, naturally) that the deadline for putting ballots in the mail would indeed be reset back to Apr. 7 (though they have to be accepted if received on or before Apr. 13). In short, wins all around for Wisconsin Republicans.

What that means is that in-person voting will move forward in Wisconsin, and that all ballots will be cast today, either in person or via mail. The polls all say that, in the Democratic presidential contest, Joe Biden is going to beat Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) by a large margin (the most recent, from Marquette, had the former veep up 28 points). However, Sanders' supporters skew young and highly engaged, while Biden's skew older and less engaged. It's certainly possible that turnout is way down, and that the great majority of the voters who decide not to cast ballots are Biden voters. If, under such circumstances, Sanders performs much better than expected, would he claim that as vindication and/or a sign that this thing's not over? Who knows?

Meanwhile, Republicans haven't paid much of a price for the various shenanigans they've pulled in the last decade or so in terms of people's right to vote. By this, we mean voter ID laws, reduced polling hours, and gerrymandering, and also the Roberts Court's consistent rulings in support of such things. However, never have these shenanigans created such a stark choice: If you want to vote, Wisconsin citizens, then you're going to have to risk your health, and maybe even your life, to do it. It's a bad, bad look. And the odor here is so unpleasant, it may reach well past the borders of the Badger State. (Z)

Trump, Biden Chat on Phone

Joe Biden said he planned to call Donald Trump so they could discuss the government's response to COVID-19. And on Tuesday, the former veep made good on that promise, chatting with the President for 15 minutes. "It was really good, really nice, I think it was very much so. I appreciate his calling," Trump said.

We pass this story along because it's front-page news everywhere, and the conversation did involve at least one, and possibly two, presidents discussing the dominant issue of the day. However, we struggle to derive any significance from it whatsoever. There is zero chance Trump is going to take advice that came from any Democrat, much less one closely associated with Barack Obama. Nor is this a sign that the President has turned over a new leaf of some sort; he already made clear he has no interest in phone conversations with Obama or even George W. Bush, who, after all, is a Republican (and knows a thing or two about leadership during a crisis). Further, within an hour of telling the press it was a good call, Trump was on Twitter taking potshots at Biden. And Biden, for his part, shot right back, so it's not like he has a claim on being the grown-up here. Anyhow, perhaps you will find meaning in this news that escapes us. (Z)

White House's Dirty Laundry Gets Aired in Public

Every day, key White House staffers have a meeting to discuss the latest as regards COVID-19. Peter Navarro, the director of trade and manufacturing policy, has become a regular attendee at those meetings. What justification is there for the involvement of someone with that job title? None; Navarro insinuated himself at his own discretion, and he gets to stay as long as he's willing to be an enthusiastic spokesman for the party line.

On Monday, that enthusiasm boiled over, as Navarro got into a shouting match with Dr. Anthony Fauci, the federal government's top expert on infectious diseases. The topic of discussion was hydroxychloroquine, which Navarro views as a miracle drug that will solve the COVID-19 crisis, while Fauci sees it as unproven. The shouting match was largely one-sided, and mostly involved Navarro screaming at Fauci.

When asked what qualifies him to assert himself in this way, Navarro insisted that he's a "social scientist" and he has a Ph.D. (which is in economics), and that "doctors disagree all the time." Very interesting, indeed. Note that (Z) is also a holder of the Ph.D. degree and is also a social scientist, and he strongly advises that you prioritize the opinion of medical doctors when it comes to, you know, medical questions. In any event, this is yet another example of a dynamic that we already knew well: those in the White House who say what Trump wants to hear can do nearly anything they want (see Kushner, Jared), while everyone else strategically bites their tongues most of the time for fear of losing their jobs.

That said, it is occasionally possible to take things a little too far (as, for example, Anthony Scaramucci learned the hard way). Less than two weeks ago, U.S. Navy captain Brett Crozier wrote a strongly worded memo to his superiors advising that the sailors on his ship (the U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt) be offloaded for their protection, in view of the virulence of COVID-19. The memo went public, creating a minor scandal that would have been forgotten by now if the administration had let it go. However, this particular administration is in the habit of turning minor scandals into major ones. And so, Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly decided to double down this weekend, and removed Crozier from his command. And then, on Monday, the Secretary doubled down yet again, and delivered a blistering speech to the crew of the Theodore Roosevelt (transcript here; audio here) in which he laid into Crozier, calling him "stupid," declaring (without evidence) that the Captain himself was behind the leak, and implying that a crime was committed.

This was an enormous blunder on Modly's part. He felt free to criticize Crozier's judgment, but the real question is: How can a man who has risen to be Acting Secretary of the Navy think it is ok to visit the Captain's former ship and smear him like that? That is what poor judgment looks like. It's clear what side the sailors are on; they cheered Crozier when he disembarked, but during Modly's speech, there were discernible catcalls and shouts of "What the f**k?" on the recording. More broadly, the Secretary has created yet another PR problem for the administration (and if Crozier wasn't already sympathetic enough, he tested positive for COVID-19 on Monday). Further, as the national-security-focused blog War on the Rocks points out, this whole mess has generally undermined sailors' trust and confidence in their leadership, as it's made it obvious where Modly's (and Trump's) priorities are. The President is now taking enough damage over this that he said he "may get involved." Modly's position is untenable here, and the smart money says he gets thrown under the bus by the time the week is out.

The problem for Trump is that once someone's been tossed, they have no particular need to hold their tongues any longer. This weekend, the President canned Michael Atkinson, the intelligence community inspector general who brought the Ukraine whistleblower's complaint to the attention of Congress. Trump thought he could have his revenge, and sneak it in under the radar by doing the deed on a Friday evening. That's two errors for the price of one. The first error was the actual firing. Not only did it look sleazy and corrupt, but Atkinson is now free to speak out, and on Monday he said that he was most certainly fired as retribution. He also strongly encouraged whistleblowers "to bravely speak up." One imagines he has a few specific subjects in mind where whistles might be blown.

The second error was the timing. It is true that COVID-19 is a huge news story right now, and has dominated every news cycle for weeks. It is also true, however, that every outlet (in particular, those that focus on politics) are hungry for any story that isn't "here's some more bad news related to the pandemic." And so, the Atkinson story has gotten extensive coverage, including a plethora of absolutely blistering editorials (see here, here, here, and here for examples).

And all of this is just one day's worth of dirty laundry. There will be much more in coming weeks, as the COVID-19 situation worsens, and nerves in the White House become even more frayed. (Z)

Small Business Loan Program Stumbles Out of the Gate

The $2.2 trillion COVID-19 relief package included nearly $350 billion to help small businesses. However, the bill was a rush job, which is understandable under the circumstances, but is also not a great beginning. Then the matter was handed over to the White House to implement, which is not a great second step. This is not an administration known for excellent planning and execution, particularly under time pressure. And not surprisingly, things have gone poorly.

Some of the issues were already baked in at the moment the program officially opened for business last Friday. To start, $350 billion isn't enough, and so small business owners are competing for slices of a too-small pie, and are often doing so up against "small" businesses that aren't so small. Further, the White House only unveiled the rules for the program on Thursday. Since it is private banks that are making the loans, they were given little time to figure things out, and to decide if they actually want to participate. On top of that, one part of those rules is that anti-money-laundering penalties will be strictly enforced. The upshot is that most banks decided to do loans only for existing clients, and in some cases with only a select list of existing clients. Slate has a good piece about a man named Rocco Frattaroli, who owns a Dairy Queen, and is exactly the type of small business owner who is falling through the cracks.

Monday, the first full day of the program, didn't go much better. The Small Business Administration system that is used to process the loans was so badly overloaded that it crashed multiple times, and was functional for perhaps half the day. Meanwhile, some banks have already decided that they have reached their saturation point. For example, Wells Fargo, which handled more small business loans than any other lender last year, announced that it would accept no more loan applications.

Several Democratic senators called for fixes to the program, up to and including possible emergency legislation to patch some of the holes that have presented themselves. Since nobody benefits from the current mess, this would seem a no-brainer. On the other hand, Washington is pretty dysfunctional these days, and patching some of the holes does not resolve the "not enough money to go around" issue. And so, each day that passes, COVID-19 relief bill v4.0 becomes more of a certainty. (Z)

House COVID-19 Inquiry Is Definitely Happening

Last week, Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA) suggested that the House should launch an investigation into what happened with COVID-19, and how to stop such a thing from happening again. Schiff even has a plan for that, modeled along the lines of the commission that looked into what went wrong on 9/11. It turns out he's not the only one, though. Three other members of the House also have plans. There are so many plans running around, one might think that Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) had switched chambers.

Anyhow, clearly this thing is happening. It's only a question of whose plan gets used and who gets put in charge. Given his performance during the impeachment, and the possibility that he's the Speaker-of-the-House-in-waiting, Schiff figures to be the favorite. At the same time, the Democrats are worried that it will look like they are using COVID-19 for political gain, and so the highly esteemed Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-SC) told reporters that the investigation "will be forward-looking" and will not focus on the early response of the Trump administration. There's likely a lot of truth there; the Democrats really do want to avoid another fiasco like the COVID-19 crisis, and they hardly need to launch an investigation in order for people to be well aware of Trump's mistakes. That said, it's hard to imagine that a proper investigation won't consider the White House's steps (and missteps) at least a little, and that at least some of that won't find its way into a few headlines. (Z)

Trump Sinks in Florida

Yesterday, we had an item about the system Florida has for unemployment applications. Set up by former governor, and now senator, Rick Scott (R), its purpose was to make it very hard to request (or get) benefits, so that Scott could brag about how low the state's unemployment was on his watch. Under current circumstances, however, the system is an utter train wreck, keeping people from getting badly needed assistance, which has some of them seeing red. Or maybe seeing blue. They can't punish Scott quite yet (he's not up again for four years), but they can certainly punish his close ally Donald Trump at the polls in November.

On Tuesday, UNF released the first poll of Florida voters taken since the COVID-19 crisis hit. The two polls of the state taken right before the pandemic had Trump leading Joe Biden by 2 points (Florida Atlantic University) and by 3 points (Univision), while the most recent UNF poll (in mid-February) had Biden up by 1 point. Now, UNF has Biden up by 6, 46% to 40%. That certainly suggests Trump is slipping due to COVID-19, an impression strengthened by the fact that 53% of respondents do not approve of the President's handling of the situation, while 58% don't trust what he says about the pandemic. And, as this thing gets worse, his numbers certainly aren't going to get better. (Z)

The Times That Try Men's (and Women's) Souls, Part VI: The Raid on Harpers Ferry (1859)

As we noted last week, crises four, five, and six are all connected, as they were all key stops on the path to civil war. Today is the concluding entry in the set (but not the series). Recall the ground rules:

- The crisis in question had to unfold over one year or less.

- The crisis had to divide the nation in a truly substantive manner at the time it happened.

- The effects had to be substantial and long-lasting.

If you care to read (or re-read) previous entries:

- The Intolerable Acts (1774)

- The Alien and Sedition Acts (1798)

- The Chesapeake Affair (1807)

- Missouri Statehood (1819-20)

- California Statehood (1850)

And now the moment where the United States passed the point of no return when it came to the Civil War:

Background: To start, let us recall two things from the previous entry. The first is that anti-slavery sentiment in the North, and pro-slavery sentiment in the South, had significantly hardened by 1850, a struggle that had deep political, economic, cultural, and moral dimensions. The second is that the process for admitting states to the union that was in place from 1820 to 1850, and that did much to keep sectional tensions at bay, was put aside in order to get California admitted. Replacing that process was an approach championed by Sen. Stephen A. Douglas (D-IL) called "popular sovereignty," which posited that the residents of a territory would, upon qualifying for statehood, vote whether to have slavery or not.

Originally, as part of the Compromise of 1850 that granted California statehood, popular sovereignty was applied only to the Utah and New Mexico territories. In 1854, however, it was extended to all future territories. And that meant that the first state where Douglas' approach was put to the test ended up being Kansas, which was ready for statehood by the mid-1850s. Assuming a legitimate election, Kansans would undoubtedly have voted to ban slavery. The state's climate and soil (outside of southwest Kansas) were not especially suited to the cash crops associated with slave labor. Further, Northern abolitionists had funded the relocation of multiple thousands of anti-slavery settlers to the territory, in a scheme similar to the "let's make Wyoming into a blue state" proposals we see today.

There were a couple of flies in the ointment, though. The first is that Southerners felt that their economy and their very way of life were in danger (they weren't necessarily wrong about this, even if that economy and way of life had a reprehensible basis). And so, they felt they needed to add Kansas to the "slave" column at all costs. The second is that election security wasn't very good back then, such that it was very easy for Russian hackers...er, sorry, for pro-slavery folks from Missouri to sneak into Kansas and cast thousands of fraudulent ballots.

The result of all of this was that when it came time to vote—that is to say, to try out popular sovereignty for the first time—Kansas ended up with not one, not two, not three, but four different state constitutions. Three of them outlawed slavery in Kansas. The fourth was written in the town of Lecompton, very near the Missouri border. It was straight outta Lecompton, as it were. Anyhow, given where (and by whom) it was written, it legalized slavery in Kansas. Everyone knew the document was a sham, but the president at that time was James Buchanan, a doughface. Keep that term in mind; it means a Northern Democrat with strong pro-Southern sympathies. Anyhow, the President knew which side his bread was buttered on, and so he threw his support behind the Lecompton Constitution. This is one of several reasons Buchanan is regarded as the worst president of all time. Or he was, at least.

Under these circumstances, with Congress controlled by pro-Northern members and the White House occupied by a pro-Southern president, there was little hope of a resolution, and indeed, Kansas would not be admitted to the union until 1861 (as a free state). Meanwhile, this very fraught process played out in a time and place where folks had no particular objections to punctuating their feelings with violence. And so, both before and after the whole constitution fiasco, anti-slavery forces (jayhawkers) and pro-slavery forces (border ruffians) inflicted much harm upon each other. That is why it's known as "Bleeding Kansas."

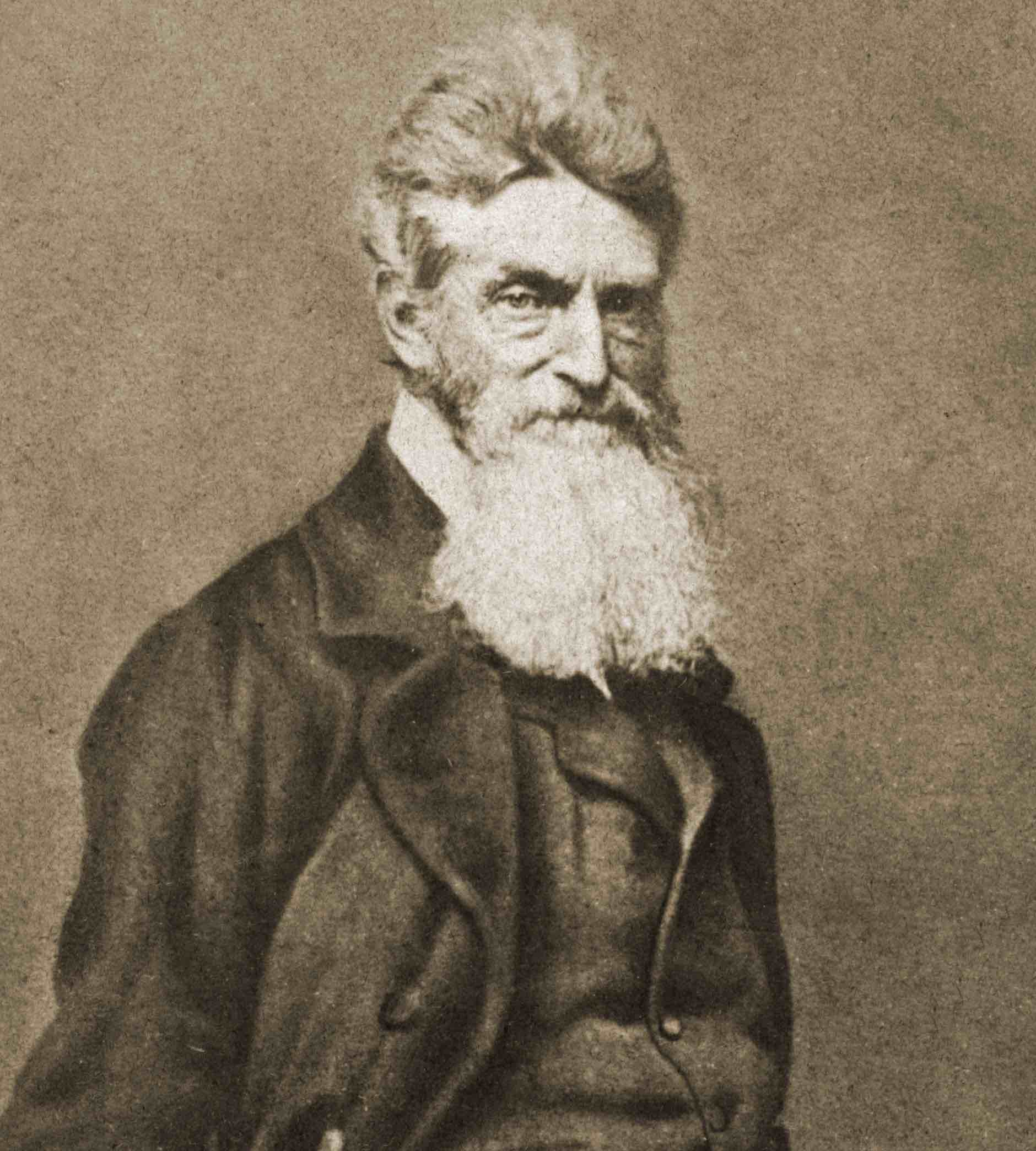

It was during this period of violence that a fellow born and raised in Connecticut became a national figure. John Brown was a comically inept businessman, with at least two dozen failed business concerns over the years. On the other hand, he had 20 children, so he wasn't incompetent at everything. In any event, he was fanatically religious, and became persuaded that God wanted him to smash the institution of slavery, Old Testament style. He even grew a beard, eventually, specifically so that he would look more like Moses:

Brown felt that events in Kansas afforded an opportunity to fulfill the mission God had chosen for him. And so, on the night of May 24, 1856, he and a group of supporters (including several sons) raided the houses of several pro-slavery residents of Franklin County, Kansas, near Pottawatomie Creek. That evening, Brown and his men killed five people in cold blood. And since there are no guns in the Old Testament, the killings were primarily done with a weapon (apparently) worthy of Moses, namely the broadsword. The Pottawatomie Massacre made Brown a hero to some Northerners, a villain to many others (who felt he was just throwing fuel onto the fire), and Satan incarnate to most Southerners.

The Incident: To Brown's chagrin, the attack on Pottawatomie did not bring an end to American slavery. In fact, all it did was make Bleeding Kansas even bloodier, as pro- and anti-slavery forces avenged Brown's attack, and then avenged that, and then avenged that. Another 29 people died in the month or so after Brown paid a visit to Kansas.

And so, the abolitionist began to plan something much grander. Over the course of the next three years, as national events caused the relationship between North and South to degrade further and faster, Brown began planning, and raising men and money for, a raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). If you ever have a chance to visit Harpers Ferry, you should really consider it, because it's basically stuck in time in the 1860s. And if you're willing to do some uphill walking, it also has a view of the intersection of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers that Thomas Jefferson said was "worth a voyage across the Atlantic" to see. (It's probably not that good, but it's pretty good.)

The reason that Harpers Ferry is stuck in time is that it used to be a very important hub of transportation and commerce. So much so that it changed hands fourteen times during the Civil War, which caused most of the residents and the local industries to flee. In other words, the very factors that eventually conspired to make Harpers Ferry something of a ghost town by 1865 were the same factors that made it a great target in 1859. It was at the confluence of, well, just about everything important in northeastern Virginia. Further, because it was close to Washington, D.C., the War Department established one of its (very few) federal armories there. In short, it offered geographic access, money, and weapons—everything an aspiring insurrectionist could want.

And insurrection was definitely what Brown had in mind. Specifically, he planned to march his small army (23 people, including several of his sons, of course) into Harpers Ferry, seize the armaments there, and then to arm the local slave population so that they might rise up against their masters. If all had gone according to Moses'...er, Brown's plan, then every slave in Virginia, and maybe every slave in the whole South, would be at war with their masters within the week.

Unfortunately, the plan was—to use military parlance—"stupid." And while Brown was good at some things, leading a military raid was not among them (even though he had assistance from a British mercenary named Hugh Forbes). Although the rag-tag force wisely cut the telegraph line leading out of town when they arrived on Oct. 16, 1859, they did not shut down the railroad, and so a train conductor sounded the alarm in Washington. Meanwhile, Brown's men were so skittish that the first person they killed was...a free black man, which is not exactly consistent with the goal of achieving racial justice. Although Team Brown did eventually capture the armory, they took far too long to take care of business. By the time the weapons were secured, a detachment of U.S. Marines, under the command of a brevet colonel named Robert E. Lee, had arrived on the scene. Lee's men surrounded Harpers Ferry and cut off all routes of escape. Then, they descended upon the armory building, killing 10 of the insurrectionists, and capturing 7 others, including Brown.

In the nineteenth century, the wheels of justice turned rather more quickly than they do today, as the government did not generally take time for pesky things like appeals. Brown was captured on Oct. 19 and his trial began just about a month after that. He was guilty as sin, of course, but even if he hadn't been, there was zero chance of a verdict other than "guilty" for an accused insurrectionist (white or black). Following his conviction, Brown was hanged on Dec. 2. He offered no final words from the gallows, but he did slip a note to his jailer before being escorted from his cell:

I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.

The punctuation and underlining are his, of course.

Aftermath: The immediate impact of the raid on Harpers Ferry was to militarize the South. Although folks in that section had previously talked about secession and forming their own country, it was mostly just talk. After Brown, however, the Southern states became deadly serious about preparing for the possibility. They began to build a stockpile of weapons and ammunition, as best they could, and also strove to develop their state militias into proper fighting forces.

The South's newfound militance also wrecked the Democratic Party. Recall that the Whig Party collapsed in 1852, unable to bridge the divide between pro-slavery Southern Whigs (like Alexander Stephens, future vice president of the Confederacy) and anti-slavery Northern Whigs (like Abraham Lincoln). The Democrats managed to paper over their differences on the national level by nominating doughfaces throughout the 1850s; Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire in 1852, and Buchanan of Pennsylvania in 1856.

The party's leaders expected to do the same in 1860, with Douglas of Illinois getting his turn. Southern Democrats would have none of it, and wanted a proper, fire-breathing, pro-slavery Southerner as the Party's standard-bearer. That was unacceptable to the Northern wing of the Party, and after the two sides were unable to work it out, they each ran a nominee. It was Douglas for the Northern Democrats and John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky for the Southern Democrats. As a result of this, everyone knew that the Republican nominee—Lincoln—would be the next president of the United States (as it turns out, he would have won even if the Democrats hadn't split, despite not even being on the ballot in the South). Lincoln's victory was so certain that the message of Douglas' campaign was not "vote for me," it was "please, please don't secede when Lincoln wins."

The Northern response to John Brown's raid was more muted, at least in the short term. Leading citizens of that section recognized that the United States was on the brink of collapse, and were not thrilled that the would-be insurrectionist had just turned up the pressure. On the other hand, most Northerners were not violently angry, in contrast to most Southerners. And there was a small segment of the Northern populace, mostly abolitionists, who saw Brown as a great hero in the weeks after he was executed. "His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine—it was as the burning sun to my taper light—mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him," observed Frederick Douglass.

Over time, and particularly after the South seceded, Brown achieved much broader acceptance as a heroic figure in the North, and a symbol of Northern righteousness and willingness to sacrifice. This was captured in one of the best-known songs of the Civil War; "John Brown's Body" (sung to the tune of an old religious hymn entitled "Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us"):

He captured Harper's Ferry with his nineteen men so true

He frightened old Virginia till she trembled through and through

They hung him for a traitor, they themselves the traitor crew

But his soul goes marching on

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

His soul goes marching on

The same tune also got another very famous set of lyrics in 1861, when Julia Ward Howe penned "The Battle Hymn of the Republic." Both songs were popular marching songs for Union soldiers, and quite often the lyrics of the two were intermixed (listen here for an example).

For well over a century, historians have debated the nature of John Brown. Was he a crazy old coot who just happened to blunder his way into a prominent place in the history books? Or was he crazy like a fox; a fellow who was willing to give his life in order to hasten the end of slavery, and who managed to do exactly that, launching the nation's descent into civil war? There have been many books on both sides of this question.

And finally, there is one other result of John Brown's raid that probably bears mentioning. Among the witnesses to Brown's hanging was a young Marylander who vehemently disagreed with the abolitionist's goals, but was deeply impressed with the value of dramatic, and even reckless, gestures in service of a cause. That fellow's name was John Wilkes Booth.

Up Next : The Homestead Steel Strike (1892). (Z)

Back to the main page