Previous | Next

Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss

It would seem that the White House has a new point person when it comes to managing the COVID-19 response. It's First Son-in-law Jared Kushner, who has reportedly set up shop at FEMA, and is overseeing both short-term management of supplies and long-term planning. Given that he's got no background in public health, already has plenty of stuff in his portfolio (reorganizing the federal government, bringing peace to Israel, combating the opioid epidemic, etc.), has had no major (or minor) successes when it comes to that portfolio, and has repeatedly demonstrated the Trump family ability for turning successful businesses into businesses on the brink of bankruptcy, this development does not give one confidence.

As recently as a couple of weeks ago, Kushner was reportedly in Donald Trump's dog house. What happened to that? Who knows, but one has to imagine that the First Son-in-law is pretty good at kissing whatever needs to be kissed. Meanwhile, what about previous COVID-19 czar Mike Pence? He's still on the job, too, which means we have two different people leading two different task forces with two different missions. That kind of decentralized approach is a Trump hallmark, whether it's a wise approach now is an open question. One also has to wonder exactly how much authority Pence has, or ever had, as Trump has now thrown him under the bus several times, including at Thursday's press briefing.

What remains clear is that to Trump, COVID-19 remains, first and foremost, a PR problem. There were many stories on that front on Thursday. Among them:

- The President is

pushing hard

to make sure that the signature on the relief checks, when they are sent out, is his.

- At the moment, by agreement between the White House and the White House Correspondents' Association (WHCA), only 15

reporters are allowed at the daily briefing each day. Major outlets get a seat every day, while minor outlets rotate.

Among the latter is One America News Network, the Trump-loving, but fairly small, cable outlet for people who think Fox

News isn't Trumpy enough. For two days in a row, OANN's Chanel Rion, who is as big a Trump fan as there is,

was present

for two days in a row when it wasn't OANN's turn in the rotation. The WHCA looked into it, and discovered that the White

House had gone behind their backs and let her in without their permission. Think about that: the administration was not

only willing to violate its own agreement, but also to put the health of everyone in the room at risk, so that Trump

could secure a tad bit more fawning coverage.

- A few days ago, Captain Brett Crozier, then the commander of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt,

wrote a memo urging that his crew be offloaded from the ship, so as to protect their health. He then circulated the memo

to 20-30 people. Apparently that was 20-30 too many, because he was

relieved of command

on Thursday for having shown "extremely poor judgment" and creating a "firestorm."

- Trump is trying out some new spin: Yes, maybe a couple hundred thousand people are going to die, but his heroic actions have saved 2 million more from succumbing.

In fairness to the President, he did (finally?) take one step on Thursday that, for two weeks now, people have been calling for: He invoked the Defense Production Act (DPA) and said that the administration was taking control of the production of ventilators and face masks. However, even that might have been primarily a PR move, as he's been getting flayed for his previous, half-hearted, invocation of the DPA, and his failure in particular to lay down the law with GM.

Meanwhile, for every step forward it seems there's half a dozen steps backward, as the White House continues to flail around. Among the news on this front on Thursday:

- The coronavirus task force

admitted

that it's only been able to round up data from half of the COVID-19 tests that have been conducted thus far.

- Plans for today's launch of the program to aid small businesses has been

described

as "chaotic," "unrealistic," and "unworkable."

- Sec. of Defense Mark Esper was

slammed

for his lack of leadership, in particular his failure to do enough to protect the health of America's servicemen and

women.

- The IRS

said

it could take up to 20 weeks for all of the stimulus checks to go out.

- Many folks, including some in Congress, are

wondering

why Trump accepted an airplane-full of supplies from Russia, giving them a propaganda victory.

- The President continued his habit of passing along bad information. On Thursday, it was a declaration that scarves are better protection against COVID-19 than masks. This is not remotely true; as the virus is small enough to make its way through most forms of cloth that might be used for scarves. In fact, because scarves absorb moisture, there are some cases where a scarf is actually more dangerous than having nothing.

In short, Mr. Kushner appears to have his work cut out for him. And the degree of difficulty here is just going to increase over time. The casualty figures are going to get worse, as is the economic downturn (more below). The President is also going to be overseen six ways to Sunday; on Thursday Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) announced the creation of a panel that will watch the White House's COVID-19 response, while Gov. Phil Murphy (D-NJ) seconded the proposal, first advanced by Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA) on Wednesday, that a COVID-19 postmortem investigation will be necessary, to figure out what went wrong. And if that were not enough, Colorado State University meteorologists announced on Thursday that the U.S. is headed for an unusually bad hurricane season, and is likely to be hit by four different major hurricanes. One wonders if, at this point, Trump wishes he'd never made that fateful trip down the escalator back in 2015. (Z)

Unemployment Figures Are Ghastly

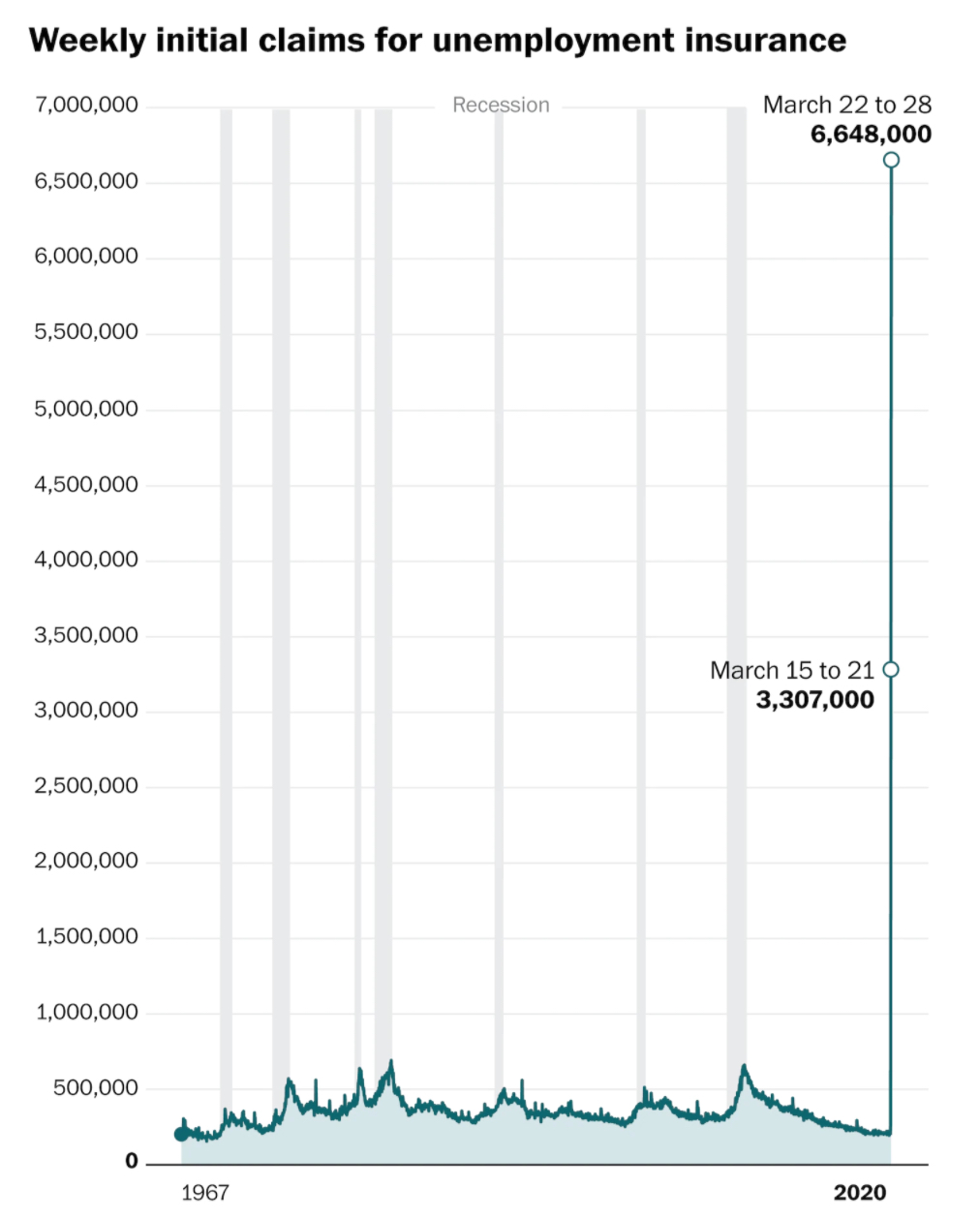

Everyone knew that the unemployment numbers for the last two weeks of March, once they came in, were going to be ugly. Nobody foresaw that it would be this ugly, though. Unemployment insurance hasn't existed for the entirety of U.S. history (or even most of it), but the previous record number of applications in a month was 695,000, in October 1982, in the midst of the early 1980s Reagan-era recession (Jul. 1981 - Nov. 1982). In the third week of March, nearly five times that many people applied. And in the fourth week, nearly ten times as many people applied. The Washington Post put together a graph to put that in context (the light gray lines represent recessions):

What can we say but: "Yikes!"? Since this is totally unprecedented, nobody can know what is going to happen next. However, the Post's economics columnist, Robert J. Samuelson, writes this:

When I began writing about economics in the early 1970s, I made a private vow that I would never use the word "depression" in describing the state of the economy. The economists and politicians who occasionally did so were, I thought, engaged in partisan hyperbole. Their game was to scare people into thinking the end of the world was at hand or to pressure Congress to enact a favored piece of economic legislation.

Well, times change. I revoke my vow.

It's not that I've concluded that we're already in a depression. But we could be. For the first time in my life, I think it's conceivable. This obviously would be a big deal. It implies permanently higher levels of unemployment (though joblessness would still fluctuate), greater economic instability and a collision between democracy and the economic system.

Sounds like a reasonable assessment to us.

Incidentally, the March "jobs report" is likely to be released today. Note that it is likely to be far less grim than the weekly figures, because the data-collection cutoff for the report is about halfway through the month (i.e., before COVID-19 hit hard). It's the April report that will be truly disastrous. Would Donald Trump have the temerity to point to the March report as evidence that things aren't so bad, after all? Probably not, but it's best to be aware, just in case. After all, knowing is half the battle. (Z)

Democrats Officially Reschedule Convention

On Wednesday, Democratic frontrunner Joe Biden shared his view that the Democratic National Convention could not go forward both (1) in-person, and (2) on the date originally planned (Jul. 13-16). On Thursday, the Party took the hint, and said they would re-schedule to the week of Aug. 17, and hope for the best.

Obviously, the Party really, really wants the pageantry of a proper convention, with the balloon drop and all. While they would prefer to make things official sooner rather than later, so that the process of unifying the Democratic electorate can begin, the delay probably don't matter all that much. Convention or no, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) is likely to be eliminated or all-but-eliminated on June 2. Maybe he drops out then, maybe before, maybe not until the convention, but whatever he does, Biden and the DNC can pivot to full general election mode after Super Tuesday II. It is also true that voters can donate $2,800 to a candidate in the primaries, and another $2,800 in the general. Biden can't spend that second $2,800 until the general begins, but he can raise it and hold it in escrow. Point is, this isn't the best news for the probable Democratic nominee, but he can adapt.

It's entirely possible that the candidate this affects most is actually Donald Trump. He wants the pageantry of a proper convention, with the balloon drop and all, too. He wants it even more than the Democrats do. When there was going to be a six-week gap between conventions, there was every chance that the Democrats would have an e-convention and the Republicans would stick with an in-person meeting. Now, however, the conventions are a week apart. The blue team won't meet in person unless they are convinced it's safe. And if they conclude it isn't, and end up with an e-convention anyhow, it will be very hard for the President to make a different decision a week later. If he does, and there is any sort of COVID-19 outbreak as a result, that will look very, very bad. "The Democrats knew it was too risky, how come Trump couldn't figure it out?" people will ask. In any case, we're now set for the longest primary season on record. (Z)

Vote-by-mail List Grows

Many U.S. states, territories, and districts, particularly those that have yet to hold primaries, are in quite a quandary right now. On one hand, sticking with in-person voting could be very dangerous, or could produce very un-democratic results if turnout is freakishly low. On the other hand, trying to switch to statewide vote-by-mail, for those states not already doing so, presents significant issues of finance, logistics, and security that will not be easy to address on an abbreviated timeline.

This week has already seen several states yield to the realities of COVID-19, and change their procedures. The latest is Wisconsin. Technically, that primary is still "in-person," and will be held on April 7, but state officials are strongly encouraging people to request mail-in absentee ballots, and on Thursday U.S. District Judge William Conley extended the deadline for requesting absentee ballots to today, and the deadline for receipt of those ballots to Monday, April 13.

Here is a list of the remaining primary states, and where things currently stand, as regards voting by mail:

| State | Last Day Votes Will be Counted | Current Vote-by-mail Situation |

| Alaska | April 10 | Election will be conducted entirely by mail |

| Wisconsin | April 13 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| Wyoming | April 17 | Election will be conducted entirely by mail |

| Puerto Rico | April 26 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| Ohio | April 28 | Election will be conducted entirely by mail |

| Guam | May 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| Kansas | May 2 | Election will be conducted entirely by mail |

| Nebraska | May 12 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| West Virginia | May 12 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| Georgia | May 19 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| Oregon | May 19 | Election will be conducted entirely by mail |

| Hawaii | May 22 | Election will be conducted entirely by mail |

| Connecticut | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| Delaware | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| District of Columbia | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| Indiana | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| Maryland | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| Montana | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| New Jersey | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| New Mexico | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| Pennsylvania | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| Rhode Island | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| South Dakota | June 2 | Vote-by-mail ballots available to all voters |

| US Virgin Islands | June 6 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| Louisiana | June 20 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| Kentucky | June 23 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

| New York | June 23 | Vote-by-mail ballots only available to qualifying voters |

A few notes:

- We believe this table and the map are entirely up to date, but it's not easy to stay on top of things, because they are changing

so fast. If anything here is incorrect, please

let us know.

- By our count, there are six states/territories/districts set to conduct their primaries entirely by mail, 12 that

are offering no-questions-asked voting-by-mail, and nine that allow voting-by-mail only for voters who have a valid

reason for doing so.

- That said, in most of the places that require a valid reason for voting by mail, the acceptable reasons are pretty

lax (for example, "I cannot travel to my polling place,") and one has to imagine that few such requests, if any, will be

denied this year.

- As you can see, most of the places whose primaries happen in the next six weeks have already shifted to all-mail

elections. The exceptions are Wisconsin, which got on the ball just a little too late, and Puerto Rico/Guam, which have

already made clear that they might re-schedule their primaries (for a second time, in Puerto Rico's case).

- The places where primaries are scheduled for the second half of May, or for June, are clearly taking a wait-and-see approach. Any of them could plausibly announce a switch to 100%-vote-by-mail at any point. Even if they don't, those states are undoubtedly going to see a higher rate of absentee balloting than they've ever had before.

In view of the increasing likelihood that the general election is conducted entirely by mail, it is surely a good thing that states are getting some practice in during primaries that will have shorter ballots (generally) and fewer voters than in November. That said, even with a trial run, it won't be easy to completely reinvent America's election system in well under a year (more below). (Z)

National Vote-by-mail Is Going to Be Tough

As we note above, a national election-by-mail in November seems more likely than not at this point. Democrats, led by Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), are pushing for it, and it may very well be written into the next COVID-19 relief bill. Some states, like Georgia and Nevada, are hustling in an effort to prepare for the possibility. Others, per the list above, have at least switched for their primaries. Op-eds pushing for national vote-by-mail are ubiquitous these days (see here, here, and here for examples).

On Tuesday, we had an item about some of the challenges of trying to conduct a national election entirely (or mostly) via postal mail. We want to focus more carefully today on what may be the biggest of those challenges, namely protecting the integrity of the election. In 2016, we had an election that was decided by a very small number of votes in several states. That resulted in the selection of a president who has no compunctions about calling into question the legitimacy of vote totals he doesn't like. And so, an election-by-mail is going to need to be as ship-shape, and as far beyond all doubt, as is humanly possible. And that's not going to be easy.

There are really three challenges here:

- American voters, by law, are entitled to keep their ballot choices secret

- Phony ballots should all be rejected

- Legitimate ballots should all be counted

Oregon and Washington pioneered vote-by-mail systems, and have gotten good reviews for them. Now Colorado, Hawaii, and Utah have also adopted vote-by-mail systems. With slight variations, the basic procedure in those places is that every registered voter in the state gets a ballot in the mail. The voter marks the ballot and in most states, puts it in a plain envelope or security sleeve with no markings. The voter then inserts the plain envelope or sleeve in an outer envelope that he or she signs. The outer envelope also contains an identifying number to make sure no one votes twice (by mail and in person or with a real ballot and a photocopied ballot). When the ballot is received by the state, the number and signature on the outer envelope are verified, and then the outer envelope is discarded and the ballot inside is processed.

To do this right, when the ballot is processed, someone has to enter or scan the ballot number into a computer, so poll workers at the in-person voting sites, if any, can verify that the person hasn't already voted. Oops. Do you see a problem here? We certainly do. Suppose some hacker—let's call him Vlad to make it more personal—hacks the system and changes the database to indicate that half the people in carefully selected precincts have already voted, even if they haven't. Of course, if all in-person voting is completely abolished and the only way to vote is by mail, this particular hack won't exist. But its sister hack—hacking the database early in the process so that legitimate ballots are rejected as duplicates when they come in—still exists, and Vlad knows that.

This notwithstanding, this two-envelope procedure seems a pretty good framework for a national vote-by-mail election, if and when Congress decrees such a thing. Many other states have more onerous requirements for verifying ballots sent in by mail. Some require that the voter submit a copy of their driver's license or other ID, but that raises the various issues involved with voter ID laws (not everyone has ID, and requiring ID tends to disenfranchise people of color, the poor, and students). Others require that some person other than the voter (in some cases, a notary) sign the ballot, but that's not especially practical, especially in the middle of an epidemic. No, it will have to be something like the Washington/Oregon system.

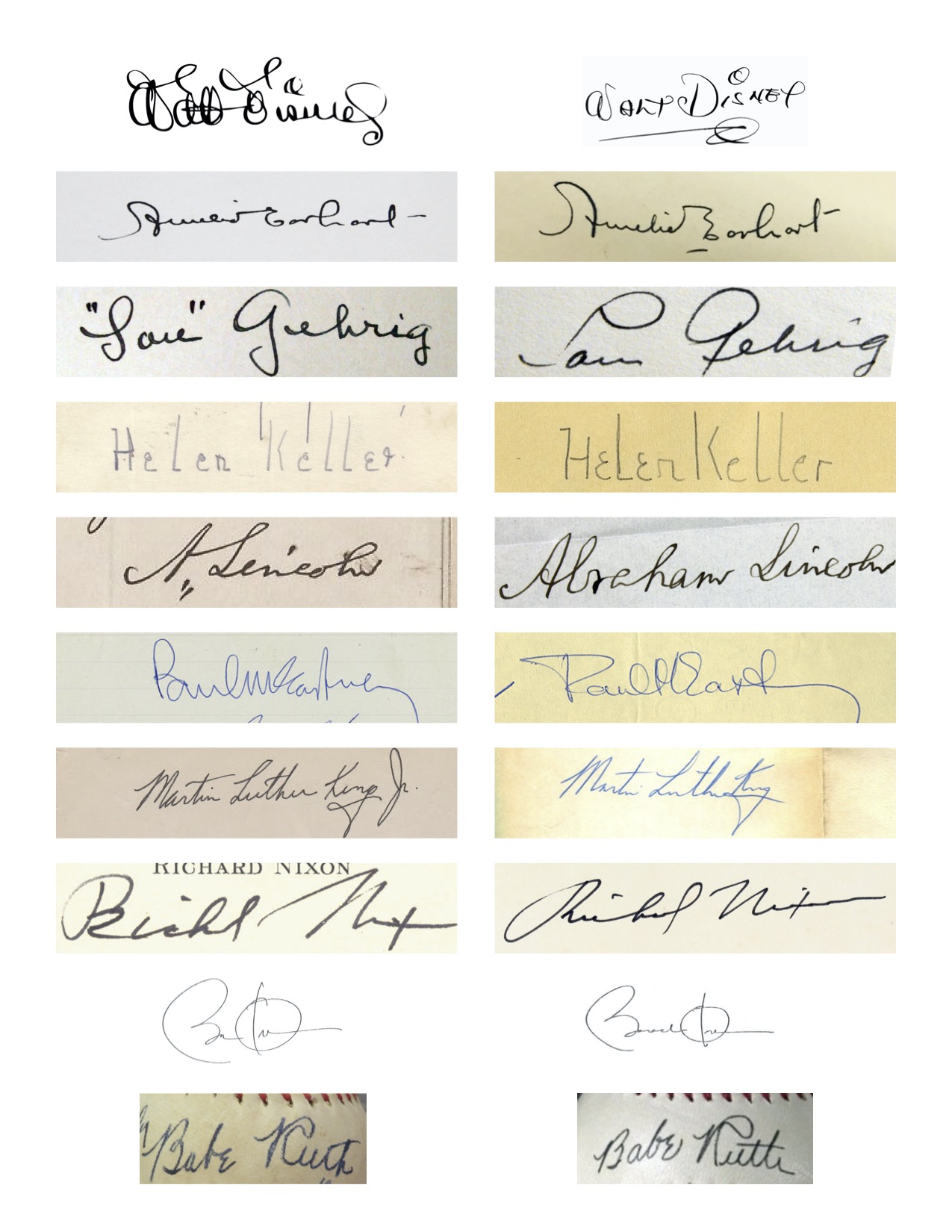

However, there are other concerns that are going to need attention sooner rather than later. To start, let's do an exercise similar to one we did a couple of years ago. The 10 celebrity signatures in the left-hand column are all real. The right-hand column, on the other hand, contains four fakes. Can you identify which four?

Just so everyone is on the same page, the 10 folks represented are film producer and entrepreneur Walt Disney, aviator Amelia Earhart, baseball players Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth, political activist and author Helen Keller, presidents Abraham Lincoln, Richard Nixon, and Barack Obama, musician Paul McCartney, and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. We tried to capture some of the common things that happen with signatures, like changes over time, or that people render their names in different ways. Anyhow, the four fakes, from top to bottom, are...Earhart, McCartney, Obama, and Ruth. Obviously, separating legitimate signatures from not-so-legitimate ones is really tough. In some states, the job is done by computers, and in others by humans. However it's done, making a comparison of only two signatures (professional verifiers need at least five or six to be confident) is inherently somewhat clumsy and ham-fisted, and should really be used only to disqualify ballots where the signature is way off.

It would be somewhat difficult to cast fraudulent ballots en masse, say by printing off 20,000 of them and sending them in. It would be possible to, say, steal all the ballots sent to the tenants of one's apartment complex and cast them all. This is the sort of fraud that would be prevented by rejecting obvious non-matches of signatures. In any event, it is likely that the number of phony ballots that sneak through will be fairly small. The bigger concern, from where we sit, is legitimate ballots being incorrectly rejected. Take a look at, for example, the Disney and Gehrig signatures above. Although the ones on the left are real, they are different enough that they could be rejected. And given that there is one political party that has recently tried to keep people from voting, and that would generally benefit from keeping turnout low, all it would take is the establishment of a "be very strict on signature matches policy" to benefit that party enormously.

This, to us, suggests a handful of steps that need to be taken, in addition to the Oregon-Washington envelope system:

- The process for verifying signatures must be standardized nationwide, perhaps using the same machines/software

everywhere, or else teams of independent verifiers.

- If a ballot is rejected, the process for "curing" that must be universal, clear-cut, and simple to

perform. Right now, the states have a hodgepodge of

approaches,

and in some cases, a person receives no warning at all if their ballot is rejected.

- Right now, Washington offers an option to receive a text alert the moment your ballot is counted. It won't be easy, but this probably needs to be mandatory for all ballots. This would be further insurance against one person voting on another's behalf ("Wait? Why did I get a text message that my ballot has been counted, when I didn't send one?") It would also be insurance against the possibility that a few thousand (or a few hundred thousands) ballots disappear into the ether, either due to incompetence or to miscreants.

In addition to these steps, it will also be necessary to mount a nationwide campaign that: (1) explains to people how to vote, (2) gives them confidence in the system, and (3) makes clear that vote-by-mail takes time to process, and that the winner of the election may not be known on Nov. 3.

All of this—designing a workable system, implementing it, and educating people about it—is a very tall order, indeed. Which means that if this is the direction things are headed, the time to get to work is now. If work on this does not begin immediately, there will be chaos in November and the Supreme Court will once again have to pick the president, probably by a 5-4 decision. And remember, when Congress counts the electoral votes in January 2021, members have the right to object to the count. It could get really, really messy. (Z)

Can Trump Postpone the Election?, Part II

Yesterday, we had an item on whether or not Donald Trump has any viable way to postpone the November elections and keep himself in power. We overlooked a few nuances that readers brought to our attention, and that we thought we would address here. Don't worry, though, our conclusion remains the same: There's no plausible way for the President to game the system.

To start, we pointed out yesterday that contrary to the dire warnings from Slate's Mark Joseph Stern, it would be effectively impossible for the 28 Republican-controlled state legislatures to step in and give their state's electoral votes to Donald Trump, despite language in the Constitution that technically gives them that power. Even if these legislators were willing to accept the fallout from such a move, we observed, Democratic governors (8 of the 28 states) surely would not sign off on the necessary changes to state law. Reader S.K. in Chappaqua, NY, points out yet another obstacle: The manner in which the final electoral tally is reported to Congress is through Certificates of Ascertainment, prepared by...the state governor. So, even if the Republican-controlled legislatures managed to overcome every other hurdle, through whatever chicanery, the 8 Democratic governors in those 28 states would simply refuse to report the results. And the remaining 20 states do not have enough EVs to elect a president.

And, if that were not enough, reader R.G. in Seattle, WA, points out that some of the dissents in Bush v. Gore (2000), most notably the one from Ruth Bader Ginsburg, argued that once state legislatures have yielded their right to choose electors, they cannot reclaim that right. Dissents are not binding precedent, of course, but this does suggest that the Republican-controlled state legislatures would not have federal law on their side if they tried to pull off a stunt like this. Anyhow, on the whole, it is clear that there are far too many obstacles for Trump to steal the election via Republican legislatures.

But what about the other path? If Trump were to persuade enough Republican governors to postpone their state elections, could he game the system that way? Reader K.N. in Boston, MA, points out an error we made in yesterday's item. We said that if the states run by Democratic governors hold their elections (which they surely would), then the House would be left with enough members for a quorum. For most purposes, we were correct. However, when it comes to resolving disputed presidential elections, the 12th Amendment defines a quorum as 2/3 of the states. In other words, to resolve a presidential election, at least 34 states have to be represented, and 26 have to vote for the winning candidate.

So, the theoretical Trump scheme would be this: Convince some sizable number of Republican governors to postpone their elections, such that nobody wins the electoral vote. That throws the election to the House, which would not have a legal quorum, and so would be unable to act. At that point, the Senate (which would have a legal quorum) meets on Jan. 6 and picks the new vice president. That person becomes president until the election is resolved.

But this scheme still would not work. First of all, the only thing this approach could plausibly achieve is to put Mike Pence in the Oval Office for some relatively brief period of time. Trump is not interested in making someone else president. Further, in this scenario, the Senate would have a quorum, but the Democrats would have a majority, so they would just choose the Democratic VP candidate. President Harris, anyone?

And if that were not enough, the Democrats have another insurance policy. Usually, the blue team is not too comfortable gaming the system. But if Trump and the Republicans engage in shenanigans, such that we end up with, say, 260 EVs for Biden and say, 50 EVs for Trump, then turnabout is fair play. The 12th Amendment specifies that the House may only choose a president from the top three EV finishers, and that the Senate can only choose a VP from the top two EV finishers. So, the Democrats could just arrange for Joe Biden to get 110 EVs, Bernie Sanders to get 80, and, say, Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D-NY) to get 70 in the presidential contest, and for Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) to get 140 and Stacey Abrams to get 120 in the vice-presidential contest. That would leave the House choosing from among three Democrats (whenever they get a quorum) and the Senate choosing from among two Democrats.

What this means, mathematically, is that the only way Trump could possibly game the system would be to convince some red-state governors to postpone their elections—a large enough number so that nobody wins the Electoral College, but a small enough number that there are enough Republicans to swing the election in the House. But if only, say, Florida, Georgia, Arizona, and Iowa postpone, it would be obvious what was happening, and there would be riots in the streets. We also don't believe that the politicians in those states would play along with such a dictatorial scheme, nor that enough members of Congress would. Further, the courts would step in and say "no, way."

And so, that leaves us where we started: It's just not doable. (Z)

The Times That Try Men's (and Women's) Souls, Part V: California Statehood (1850)

The first set of three crises had to do with the Revolution and its aftermath. The second set, of which this is the second entry, all deal with slavery and the lead-up to the Civil War. Recall the ground rules for the series:

- The crisis in question had to unfold over one year or less.

- The crisis had to divide the nation in a truly substantive manner at the time it happened.

- The effects had to be substantial and long-lasting.

If you care to read (or re-read) previous entries:

- The Intolerable Acts (1774)

- The Alien and Sedition Acts (1798)

- The Chesapeake Affair (1807)

- Missouri Statehood (1819-20)

And now the story of how the admission of the Golden State was a miner [sic] problem for the U.S.:

Background: California may have 40 million people today, but for most of its history, it was way at the other end of the spectrum. There was a fairly sizable Native American population by premodern standards, perhaps 150,000 individuals by the year 1500. As to people with European heritage, however, the state was too remote, too short on water, too hot, and too full of unfamiliar plant and animal species. Consequently, during the Spanish era (1530s to 1821), there were no more than 1,000 non-natives living in California. During the Mexican era (1821 to 1849), the non-native population grew to perhaps 7,000, most of them lured by giant grants of free land (50,000 acres, on average).

Despite all of this, the leaders of the United States spent virtually the entire Mexican period lusting after California. There were several reasons for this. They were concerned, first of all, that a hostile foreign power, one much stronger than Mexico, might grab the territory and then would become a big headache (the Brits were the obvious possibility). Further, Americans of that era came to believe that God wanted them to be a bicoastal power, a notion that would eventually give rise to the slogan "manifest destiny" (somehow, God rarely seems to issue corrections in these situations). Perhaps the most important reason the U.S. government wanted California, however, was that even in the 1820s and 1830s, Americans aspired to be an economic powerhouse. Back then (and today, for that matter), that meant substantial trade with Asia. And to trade with Asia, you need western ports, which California most certainly has.

For the better part of two decades, the U.S. government tried various schemes in an attempt to acquire California. There were several offers to purchase it, or to make some sort of trade. The Mexican government rejected all of these advances. Then, the U.S. sent a fellow named Thomas Larkin, whose official job was consul, but whose real job was to convince the people of Alta California to revolt against Mexico, just as Texas had. When all of these efforts failed, it became clear that a war would likely be necessary.

In 1844, Americans elected Democrat James K. Polk of Tennessee as president. He ran on an expansionist platform, including the acquisition of California, and he was serious about fulfilling his promises. After spending some time on the northwest boundary of the country, in 1846 he turned his attention in Mexico's direction. While he realized a war would be necessary, he also knew that—politically—he had to make it look like the U.S. was acting in self-defense. So, what the President did was send several thousand troops to the (disputed) border between Texas (by then admitted as a U.S. state) and Mexico. The Mexicans, mindful of their interests, sent their army to the border. Polk knew that if you have two hostile armies staring across a river at each other, someone is going to get skittish and fire a shot. And that is exactly what happened on April 25, 1846, as a detachment of Mexican soldiers fired upon a group of Americans.

Once the news reached Washington (not a quick process back then), Polk asked Congress for a declaration of war. The opposition Whig Party, with a freshman representative from Illinois taking the lead, suspected that the U.S. had goaded the Mexicans into an attack, and that a fair part of the President's motivation was to acquire territory for future slave states. They weren't necessarily wrong about either of those suppositions. Anyhow, that representative introduced several "spot" resolutions in the House demanding to know the circumstances under which hostilities began, and in particular, where the first spot of blood was spilled. After all, if the first wounds were inflicted on American soil, that made Mexico the aggressors, whereas if they were inflicted on Mexican soil, the opposite was true. Ultimately, the spot resolutions didn't go anywhere, and Polk got his declaration of war. That unfortunate congressman, who lasted for only that one term, was haunted for many years by his maneuverings; political opponents mocked him as "spotty" Abe Lincoln.

When the war came, the Mexican and the American armies were relatively even opponents...on paper. In practice, however, the U.S. had the upper hand, and it wasn't even close. The American army was better trained, better equipped, and had better leadership. If you don't believe us, perhaps you will believe another key Civil War figure. General Ulysses S. Grant served in Mexico (then as a captain), and he recorded this observation in his memoirs:

The Mexican army of that day was hardly an organization. The private soldier was picked from the lower class of the inhabitants when wanted; his consent was not asked; he was poorly clothed, worse fed, and seldom paid. He was turned adrift when no longer wanted. The officers of the lower grades were but little superior to the men.

This may sound like rah-rah nationalism, but Grant actually goes on to explain that he was deeply impressed by how well the Mexicans fought, despite their disadvantages. He was also disdainful of the overall U.S. war effort, writing that the Mexican War was "the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation."

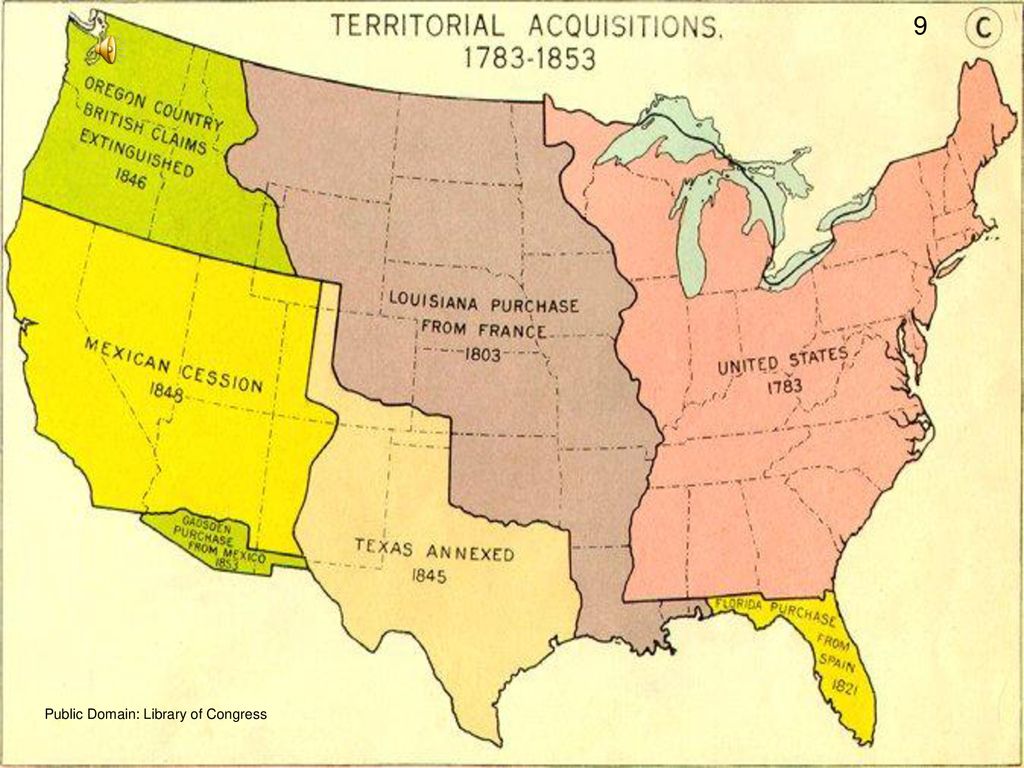

In the end, the U.S. only lost one battle during that war (San Diego), and compelled the surrender of the Mexicans in early 1848. The only reason the conflict took as long as it did is that heat and tropical disease made fighting impractical six months a year. Once the war was over, the U.S. negotiated a treaty in which they received half of Mexico's land in exchange for a nominal payment ($15 million, or about $449 million in modern dollars):

The purpose of the payment was to give the whole thing a veneer of being a business transaction rather than a land grab. But it was a land grab, have no doubt about that.

At this point, let us now jump far back in time. One of the last things that the Confederation Congress did, before disbanding, was pass a law called the Northwest Ordinance. And one of the first things the U.S. Congress did, after coming together for its first session, was affirm the Northwest Ordinance. In other words, we're back in the 1780s right now. What the Northwest Ordinance did was set out a series of steps by which land acquired by the U.S. could be organized into a territory, and then finally a state, based on reaching certain population targets. This process was designed around the population sizes of the 18th century, and so the targets were in the thousands of people. For example, at 5,000 people, a territorial legislature can be elected. At 10,000, a territorial governor. Once the population reached 60,000, statehood became available. This process was designed to take a long time—years, decades, maybe even generations. Note, for example, that Utah was acquired at the same time as California, and yet it did not become a state until 1896 (48 years).

California, as it has done so many times over the course of the past two centuries, marched to the beat of a different drummer. Largely by chance, within weeks of the dawn of the American era, gold was discovered outside of Sacramento. It actually took a while for the news to make its way across the country, but in 1849, people arrived by the hundreds of thousands in search of fame and fortune. Few found it, unless they happened to be in the business of making chocolate or manufacturing blue jeans. Anyhow, as a consequence of all these arrivals, the state jumped right to the end of the Northwest Ordinance's checklist, and its residents were ready to write a constitution and request statehood by early 1850. To this day, California remains the only state (other than the original 13) that was never legally a U.S. territory.

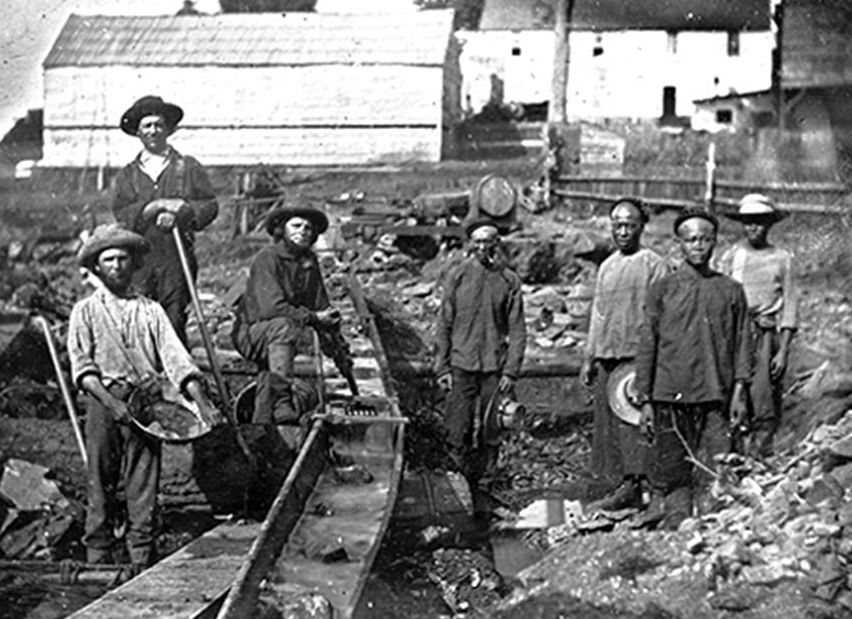

When trying to make sense of the original California constitution (which was eventually replaced in 1879), it is important to understand that life as a gold miner really, really stunk. Forget what songs like "My Darling Clementine" tell you, it was hard, dirty work that included long days and little time off. Look at the filth (not to mention the sunburns) on these poor fellows:

Despite what the advertisements that lured them said, there wasn't actually that much money to be made, primarily because the costs of everything (clothes, pans, picks, dynamite) was grossly inflated. There were also virtually no women. On the rare evenings off, the miners would hold dances, and the dances of that era (square dances, quadrilles, etc.) required female partners. With females in short supply, there was little option but for some of the men to cross-dress. There's a fairly famous story of a grizzled old (and probably drunk) 49er who took a fancy to his dance partner, reached under "her" dress in search of a cheap feel, and came up with rather more than he expected. "How do you like the view?" asked the "woman." Sort of a 19th century version of the Kinks song "Lola."

Anyhow, since most of the folks in California in 1850 were miners, that first constitution was written to accommodate their desires. It gave, by the standards of the mid-19th century, liberal rights to women (they could hold property, initiate divorces, etc.). This wasn't because the 49ers were proto-feminists, it's because they were tired of dancing with dudes. Similarly, and of even greater consequence, the 1850 constitution banned slavery. This is not because the 49ers were early civil rights advocates, it's because they did not want to compete against slave labor.

The Incident: As we discussed in the last entry, the Southern commitment to slavery was pretty entrenched by 1820, as was Northern opposition to the institution. Those sentiments grew much deeper, and ensnared far more people in each section, over the next 30 years. It is instructive that Southerners had grown entirely comfortable excusing the downsides of slavery by 1850, using the euphemism "our peculiar institution." They also bragged that cotton was "king." And it was; in 1820 the South produced 450,000 bales. By 1850, they were producing more than 4 million bales a year.

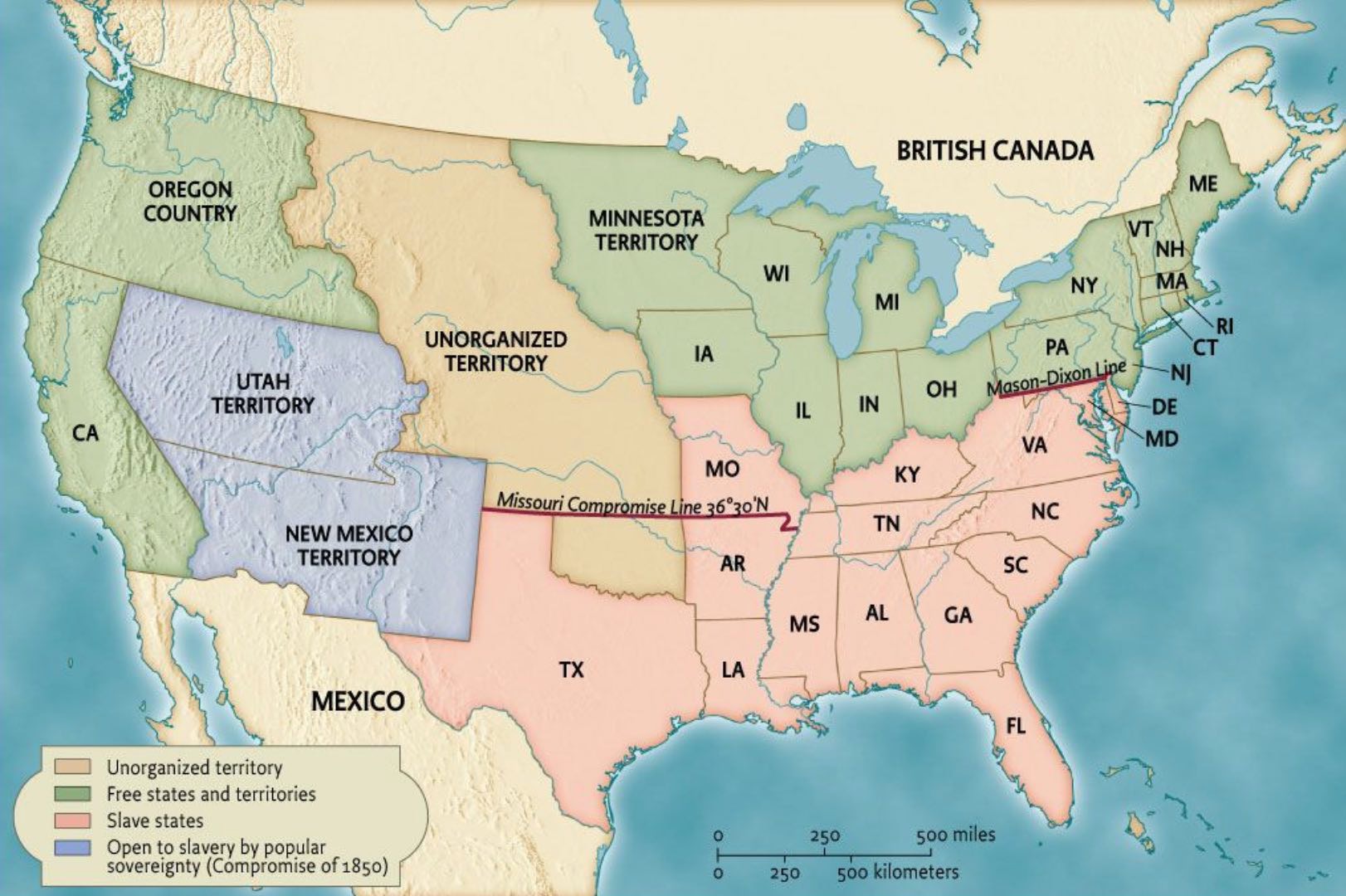

To a very large extent, what kept the peace between sections was that they both made a point of abiding by the Missouri compromise of 1820. That agreement managed the admission of not only Missouri, but eventually 6 additional states, 3 of them slave (AR, FL, TX), 3 of them free (MI, IA, WI). California presented a real conundrum, though. First of all, there was no slave state ready (or close to ready) to join with it, so as to maintain the balance between free and slave states. Further, the Missouri Compromise line clearly doesn't work with the Golden State, as it cuts right through it:

If that were not enough, another big part of the reason that the peace was maintained between 1820 and 1850 was the efforts of the centrist Henry Clay (who worked out the Missouri Compromise in the first place), the prominent Northern spokesman Daniel Webster (W-MA), and the prominent Southern spokesman John C. Calhoun (D-SC). This trio was known as the "great triumvirate" of the Senate, and generally when there was a major problem between 1820 and 1850, they'd sit down and figure it out. By 1850, though, all three were in the twilight of their careers (and, in fact, by 1852 they would all be dead).

With California's admission a looming crisis, and the great triumvirate largely sidelined, that created an opening for some other politician to seize the day. The one who did so was Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, a centrist Democrat known as the "Little Giant" (due to his forceful oratory, as well as the fact that he was only five feet tall). Recognizing that the Missouri Compromise was kaput, he got to work on a successor compromise known as the Compromise of 1850 (they worked very hard on that name). There were numerous elements to the compromise, but the three that matter for our purposes:

- California was admitted as a free state (giving the non-slave states control of the Senate)

- In exchange, the South was given a much stronger Fugitive Slave Act, as runaway slaves had become a big and

expensive problem for them

- The New Mexico and Utah territories were organized, and the future of slavery in those places was to be decided by a future vote of the territories' residents. This "compromise" position on slavery was called "popular sovereignty."

The compromise was not especially popular with voters, and it only made it through Congress due to vast amounts of arm twisting by Douglas. Even then, President Zachary Taylor said he intended to veto the bill. However, he died suddenly, possibly due to eating spoiled cherries. Or maybe he was poisoned with arsenic. Anyhow, the newly elevated president, Millard Fillmore, applied his signature.

Aftermath: There was a whole generation of scholars who took the position that the Civil War was entirely avoidable, and that it only happened because of a "blundering generation" of politicians. (Z), our resident historian, doesn't buy it. With that said, the Compromise of 1850 certainly proved to a be a huge blunder that took an already difficult situation and made it much worse.

The first thing that became clear was that the Northern public really hated the Fugitive Slave Act. Few of them saw black folks as equals, but they also found offensive the very real possibility that a non-slave could be grabbed, accused of being a runaway, and put into bondage. They also perceived the Fugitive Slave Law as an imposition on their liberties and their rights of self-governance (a crude equivalent today would be if red-state members of Congress tried to shut down all the Planned Parenthood clinics in blue states...oh, wait). Anyhow, Northerners got in the habit of subverting the law, often going so far as to break a captured "slave" out of jail. This, in turn, angered the South, who felt they had been played for suckers when they agreed to California's admission.

It also occurred to partisans on both sides that this whole popular sovereignty thing had the potential to subvert long-held understandings about slavery. Southerners feared that Arizona, which they had assumed would be a slave state, might enter as a free state. Northerners feared that Utah, which they had assumed would be a free state, might enter as a slave state. Further, there were doubts on both sides that the scheme could actually work as advertised. All of this was too much for the Whig Party to overcome, and they collapsed in 1852, to be succeeded by the newly formed Republican Party, founded in Wisconsin in 1854. When popular sovereignty was actually put to the test—not in New Mexico or Utah, but in Kansas—it did fail disastrously, proving the doubters correct.

In short, the 1850s was like a series of dominoes, metaphorically speaking, with the fall of the last domino leading to the bloodiest and most destructive war in the nation's history. The admission of California, with a constitution attuned to the needs of a bunch of gold miners, was the first domino.

Up Next : The Raid on Harpers Ferry (1859). (Z)

Back to the main page