Previous | Next

Trump Gets Real about COVID-19

Donald Trump's daily COVID-19 briefings are still packed full of falsehoods and attempts to rewrite history. However, reality is also starting to take hold. On Tuesday, acknowledging the "hard days that lie ahead," the President said that even with nationwide adoption of stringent mitigation efforts (something that has not happened yet, of course), the death toll in the next several weeks projects to be between 100,000 and 240,000. Trump also suggested that if the number can be kept closer to 100,000, that will mean he's done a "good job."

One wonders what caused Trump to have his (semi-) "come to Jesus" moment. Certainly it wasn't Jesus himself; if the Lamb of God is talking to anyone these days, it's not Donald J. Trump. Maybe newly anointed Chief of Staff Mark Meadows got to the President, or maybe Dr. Anthony Fauci's words finally began to sink in. Our best guess is that Trump has figured out (or had it explained to him) that people in "his" states are about to be hit really hard. There are many reasons for this, among them a habit of holding irresponsible large gatherings (like church services and funerals), inadequate COVID-19 testing, and a large number of uninsured or under-insured residents (which is due, at least in part, to many red states' turning down Medicaid expansion).

Just because the President has gotten serious about the epidemic doesn't mean he's pulled things together in terms of combating it, though. There remains no centralized management and/or distribution of resources. When asked on Tuesday about the shortage of ventilators, administration officials shrugged and suggested sharing. Meanwhile, the Pentagon said that it's still sitting on the 2,000 ventilators from its supply that it promised to share, because...nobody has told them where to send the equipment. Trump also put the kibosh on a plan to re-open Obamacare enrollment, so that sick and/or potentially sick people can get insurance. This decision was not explained; readers will just have to make their best guess as to what the problem was (hint: It isn't the "care" part of it). Perhaps the best indication that the President is not particularly interested in the hard work of taking a disastrous situation and making it into a merely bad situation is that he continues to pursue "miracle" solutions; the latest is an unproven Japanese drug called Avigan.

Meanwhile, consistent with the view that this is primarily a PR problem—and now, a very serious PR problem—Republicans are looking for ways to blame the whole thing on the Democrats. This is not an easy logical leap to make, since the Republican Party controls most of the federal government, and the Democratic Party's signature issue for more than a decade has been better and more widely available healthcare. Nonetheless, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (undoubtedly in conversation with other Republican leaders) thinks he has a way. On Tuesday, he sat with Hugh Hewitt for an interview and said: "[COVID-19] came up while we were tied down on the impeachment trial. And I think it diverted the attention of the government because everything every day was all about impeachment."

That doesn't work so well timeline-wise (only the very earliest days of COVID-19 overlapped with impeachment), nor does it explain why Trump and his administration could not do two things at once (especially since the President found time for plenty of unnecessary tweeting during the trial). McConnell's thesis also does not explain the near-total lack of action on COVID-19 between the end of the impeachment trial (Feb. 5) and, say, the formal declaration of a national emergency (Mar. 13). Still, guess you gotta go with what you've got; we'll see if the right-wing media picks this up and runs with it. (Z)

A Grim Mortality Milestone

Another 1,100 Americans died from COVID-19 on Tuesday, bringing the total number of Americans who have succumbed to more than 4,000. That means that the country just surpassed two unhappy milestones. First, there have now been more deaths in the U.S. from COVID-19 than in China. Second, there have now been more deaths from COVID-19 than there were from the 9/11 attacks (2,977).

Strictly speaking, the difference between 2,800 and 2,900 deaths should be exactly the same as the difference between 2,900 and 3,000 deaths. In reality, however, it does not work that way. Human beings are not especially good, cognitively, at grasping the differences between large numbers. Further, when those numbers get more and more "negative" as they get larger (as in death tolls), there is a built-in defense mechanism called "psychic numbing" that tends to make each higher number a little less impactful. Consequently, the difference between "100 dead" and "1 dead" actually tends to feel much bigger than the difference between 11,000 dead and 10,000 dead, even though 1,000 people is obviously far more than 99 people.

Because of this, there is also a cognitive tendency that works in the opposite direction. As it is hard to process the difference between 2,000 and 3,000 deaths, humans tend to think in terms of reference points. What that means is that while the jump from 2,900 dead to 3,000 dead is not incredibly impactful, the jump from 2,900 dead to "more dead than on 9/11" is. Here is where COVID-19 now stands, as compared to some other notable large-scale losses of American life:

| Event | Year(s) | Americans Dead | Notes |

| Las Vegas shooting | 2017 | 58 | Worst mass shooting in U.S. history |

| Oklahoma City bombing | 1995 | 168 | Deadliest domestic terrorist attack in U.S. history |

| Sinking of the Titanic | 1912 | 238 | Overall death toll (including non-Americans) estimated at 1,635 |

| Hurricane Katrina | 2005 | 1,836 | Estimated |

| Johnstown Flood | 1889 | 2,209 | Worst man-made disaster of the 19th century; estimated |

| Bombing of Pearl Harbor | 1941 | 2,467 | Deadliest military strike on U.S. soil |

| Hurricane Maria | 2017 | 2,982 | Estimated |

| 9/11 attacks | 2001 | 2,997 | Deadliest terrorist attack in world history |

| San Francisco earthquake | 1906 | 3,000 | Estimated |

| Battle of Antietam | 1862 | 3,675 | Deadliest single day in U.S. history |

| COVID-19 | 2020 | 4,000+ | |

| Galveston hurricane | 1900 | 6,000-12,000 | Worst natural disaster in U.S. history; estimated |

| Battle of Gettysburg | 1863 | 7,058 | Deadliest battle in U.S. history |

| H1N1 | 2009 | 12,469 | "Swine flu" |

| Revolutionary War | 1776-83 | 25,000 | Estimated |

| Normandy campaign | 1944 | 29,204 | Deadliest military campaign in U.S. history |

| Vietnam War | 1964-71 | 58,209 | Military deaths only |

| World War I | 1917-18 | 116,516 | Military deaths only |

| COVID-19 projections, 3/31/20 | 2020 | 120,000-240,000 | |

| World War II | 1941-45 | 405,399 | Military deaths only |

| Spanish Flu | 1918-19 | 675,000 | Estimated |

| Civil War | 1861-65 | 800,000 | Military deaths only; estimated |

We tried to select all of the significant reference points that might reasonably come up in conversations, op-eds, etc. in the next six months. And every time one of these signposts is passed, it surely works to the disadvantage of Donald Trump's 2020 reelection hopes, especially since he already has Las Vegas and Hurricane Maria on his résumé. In particular, we doubt that "more deaths than in the entire Vietnam War" will translate into "Good job, Mr. President!" in the minds of most folks. At the same time, great crises tend to lay the groundwork for big changes. The U.S. is going to be a very different country a year from now, and the higher that COVID-19 climbs on this list, the more different the country is going to be. (Z)

A Grim Economic Milestone

Everyone knows, at this point, that the Dow Jones has had a lousy month. And now that the month (and the quarter) are over, we know exactly how bad. With an overall decline of 23.2%, it was the worst first quarter in the 135-year history of the Dow Jones industrial average.

Other indicators were also bad, albeit in not quite as "historic" a fashion:

- The S&P 500 had its worst quarter since 2008 (a.k.a. the midst of the Great Recession)

- Both the Dow (-13.7%) and S&P (-12.5%) had their worst months since October 2008

- The NASDAQ (-10.1%) had its worst month since November 2008

- U.S. oil prices dropped 54% in March, the worst month (by far) since oil futures began trading on the New York Mercantile Exchange in 1983. The previous worst drop was 33% in, you guessed it, October 2008. The average price of a gallon of gas is now under $2/gallon.

Obviously, there's going to be unhappy news on the unemployment front coming soon, too.

In our experience, trying to predict what the economy will do is a fool's game. That said, the stock market had disastrous months in September and October of 2008, at the height of the Great Recession, and the federal government dumped big piles of cash into the economy in October 2008 (TARP) and again in February 2009 (ARRA). The recession ended in June 2009. If we assume that the current crisis follows the same script (big assumption), then Congress will dump another one or two trillion dollars into the economy sometime this summer, and the recovery will begin around Thanksgiving. (Z)

Obama Is Not Happy

In an apparent effort to use COVID-19 to sneak a few things in under the radar, the Trump administration this week said that it was dialing back the tougher automobile emissions standards set by the Obama administration. Consistent with a well-established policy of gaslighting the voting public, Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao announced the decision thusly: "By making newer, safer, and cleaner vehicles more accessible for American families, more lives will be saved and more jobs will be created." It is plausible that more lax emissions standards will create more jobs (e.g., for funeral home workers), or that it will make vehicles more accessible. But to suggest that the laxer standards will also make the vehicles cleaner and will save lives? That's an insult to the intelligence of the American people, reminiscent of Ronald Reagan's voodoo economics.

This change has been bandied about in the White House for three years. There's really no reason it couldn't have been announced two years ago, or that it couldn't wait for another six months. That it came right now, in the midst of an all-encompassing national crisis, is not a coincidence. Meanwhile, automobile manufacturers can't really adapt to the new standards, knowing full well that they could be changed again in less than a year. So, it's doubtful this was done at their instigation. More probably, it's an attempt to throw a bone to the struggling petroleum industry (see above). Plus, Team Trump always likes a chance to poke Barack Obama in the eye.

However, nobody likes to be poked in the eye, including Obama. And while he has generally bit his tongue as Trump tries to dismantle his legacy, #44 did not remain quiet this time. In a tweet that already has considerably more "likes" than any Trump tweet this year, Obama deftly connected the current pandemic with the Trump administration's environmental policy:

We've seen all too terribly the consequences of those who denied warnings of a pandemic. We can't afford any more consequences of climate denial. All of us, especially young people, have to demand better of our government at every level and vote this fall. https://t.co/K8Ucu7iVDK

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) March 31, 2020

Trump does not appear to have responded, thus far. On one hand, the Donald does not like to let slights go unanswered. On the other hand, he prefers to punch down, and he can't do that with Obama.

In any event, this brings up an interesting element of the 2020 election, an X-factor (or maybe an O-factor). Although Obama, like his predecessors, has bowed to the custom of staying out of the primaries, it's historically been 100% kosher for a former president to campaign in the general election. We haven't had a lot of that in recent years; most recent presidents have left office physically unable to campaign in the next presidential election, or else unpopular to the point that they are a liability to their party. Obama, by contrast, is in fine shape and is as popular as he's ever been. The assistance he will render to his former veep could be substantial, even if it has to be virtual. (Z)

Maybe Biden Shouldn't Worry about Appeasing Sanders

Jennifer Rubin is the Washington Post's resident NeverTrump conservative (along with Max Boot), and she has an interesting piece on how Joe Biden should deal with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), under the provocative headline "The benefit of the Democrats denouncing Sanders's selfishness."

Her basic argument, as the headline makes clear, is that Biden shouldn't try to curry favor with Sanders at all. She has three basic reasons:

- It would make perfectly clear that Biden is not Sanders and not a crazy left-winger:

Everyone knows that Donald Trump is going to slur his Democratic opponent, even if they're to the right of Ronald

Reagan, as a crazy, wild-eyed socialist who is to the left of Che Guevara. Rubin suggests that having Sanders to point

to would help blunt this line of attack. She doesn't mention it, but the obvious

historical parallel is the election of 1948, where it seemed that Democrat-turned-Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond would steal

votes from Harry S. Truman. However, Thurmond's candidacy actually helped affirm the argument that Truman was the

sane, non-racist Democrat in the race, and allowed the President to be reelected.

- It will make governance in a Biden administration much easier and more cohesive: This one

is pretty obvious; every policy promise that Biden makes to Sanders, and every slot in his administration that Biden

gives to Sanders, makes Biden's leadership less focused and less coherent.

- It would free up constructive, smart progressive leaders such as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) to lead that wing of the party: The very fact that Sanders continues to campaign suggests he's either unwilling to accept that he can't have everything he wants, or else that his own personal needs are more important than implementing his political program. Though Warren is actually to the left of Sanders as judged by her votes in Congress, she's also more of a pragmatist. It is also interesting to note that Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), who is likely to succeed Sanders as the leader of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, has lately adopted a style much more in the mold of a "Warren-style pragmatist" as opposed to a "Sanders-style idealist."

As we have pointed out before, we're not talking about Sanders' entire base of support here. Some percentage of them will hold their noses and vote for any Democrat, including Biden, for fear of reelecting Trump. And some of them will definitely vote Trump or will vote third-party if Sanders is not the nominee, and so are lost to Biden. The only group that matters here are the persuadables; the Sanders supporters who are neither guaranteed to vote Democratic nor guaranteed to vote Trump/third-party. Our guess is that this is a fairly small fraction of the Senator's base; maybe 10% at most, which would make them 3-4% of the Democratic electorate, or roughly 1% of the overall electorate. It's certainly possible that sacrificing those folks in search of the three benefits outlined by Rubin would make good tactical sense. And if Biden begins to treat Warren, or Ocasio-Cortez, as the "spokeswoman" for the progressive wing, and to have them as part of his team, he might be able to do even more to limit the damage caused by turning his back on Sanders. (Z)

Mike Francesa Slams Trump

The odds are good that, unless you live in New York City, you don't know who Mike Francesa is. For the uninitiated, he's the dean of sports talk radio in that city, and has been entertaining folks there for decades with his acerbic takes on the Mets and the Knicks. He's also a center-right conservative, and has openly supported his former fellow New Yorker Donald Trump since 2015.

Until now, that is. This week, Francesa has ripped into the President multiple times over his handling of the COVID-19 crisis. For example:

How can you have a scoreboard that says 2,000 people have died and tell us, "It's OK if another 198,000 die, that's a good job." How is that a good job in our country? It's a good job if nobody else dies! Not if another 198,000 people die! So now 200,000 people are disposable?

The radio star has also taken exception to Trump's general lack of action when it comes to managing the supply of medical equipment, as well as his odd promotion of "MyPillow guy" Mike Lindell for political office.

Francesa is exactly the sort of voter that Trump must have in 2020; a white ethnic (he's Irish and Italian) with conservative leanings. Those folks will be the difference maker in states like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. It's true that he's just one guy, but his defection from Team Trump is just a bit more evidence (like the Rasmussen polls we discussed yesterday) that the President might actually have lost some of his base due to COVID-19. Further, while Francesa does not have the influence of, say, a Sean Hannity or a Rush Limbaugh, he is still an "influencer" or, to use a slightly more scholarly term, a "maven" (information specialist). He's not likely to persuade anyone to turn on Trump if they're not already leaning that way. However, Francesa's apostasy, and that of media figures like him, certainly could be a signal to such folks that it's become ok to jump ship. (Z)

The Times That Try Men's (and Women's) Souls, Part IV: Missouri Statehood (1820-21)

Another of the great crises of American history. Recall the ground rules:

- The crisis in question had to unfold over one year or less.

- The crisis had to divide the nation in a truly substantive manner at the time it happened.

- The effects had to be substantial and long-lasting.

If you care to read (or re-read) previous entries:

And now we will show you how the Show Me State nearly wrecked the union:

Background: Let's start with a question: On the day the Constitution was adopted in 1787, what state was home to the largest anti-slavery society in America? Think about the answer; we'll get back to it shortly. At the moment, however, we'll note that the first slaves likely came to British North America in 1619 (hence The New York Times' 1619 project). The reason we say "likely" is that the exact legal status of the "twenty and odd negroes" who arrived in 1619 is not perfectly clear. Also, it's possible that one or more slaves arrived prior to that, but that their existence did not make its way into the documentary record left to us (which, before about 1750, is pretty spotty).

Anyhow, it took a number of generations for the American slave system to ripen to maturity. In part, this was because the mortality rate of the early-to-mid 17th century was very high, such that slaves did not make much economic sense. A slave was not cheap (anywhere from $5,000 to $100,000 in modern dollars), and the break-even point tended to be about 7 years after purchase. Until the 1660s or so, new arrivals from Africa tended to live less than 7 years, so the math didn't add up.

On top of that, it is difficult to overstate the inherent difficulties of maintaining a slave-based economy. Beyond the high startup costs (slaves, land, supplies, etc.), slaves had every motivation to shirk their work and to engage in various acts of rebellion (faking illness, stealing food, damaging equipment). There was also constant concern about a large-scale slave uprising. The details of the violent Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804, which is the most famous and successful mass slave rebellion in history, would have turned slave owners white, if not for the fact that they already were.

Ultimately, the slave system did become established, primarily in the South, and primarily for the production of tobacco. Though it may have been "lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse," according to King James I, there was big money in tobacco, which didn't grow particularly well in most parts of Europe. In search of these big profits, Southern plantation owners were willing to accept the downsides of a slave system.

The problem with tobacco as a crop, however, is that it really sucks nutrients out of the soil. They had some tricks back then to compensate, like allowing fields to lay fallow for a year. But after a century of raking in the profits, tobacco production was in serious decline by the 1750s, and many slave owners were having trouble making ends meet. Some of them tried alternative crops (diversifying into hemp and indigo was a big part of George Washington's financial success, as he was largely able to avoid the downturn of the 1750s and 1760s). However, there were few crops that: (1) would grow properly in the depleted Southern soil, and (2) were in high enough demand to be highly profitable for a sizable number of slave owners.

And so it is that the largest anti-slavery society in the United States, on the day that the Constitution was adopted, was in...Virginia, the state that was also home to the largest number of slaves. It is not the case that all Virginians, or even most, were anti-slavery. However, there were certainly some Virginians who felt that the overall costs of a slave system were no longer worth it, and who wanted the Southern economy to chart a new, slave-free course.

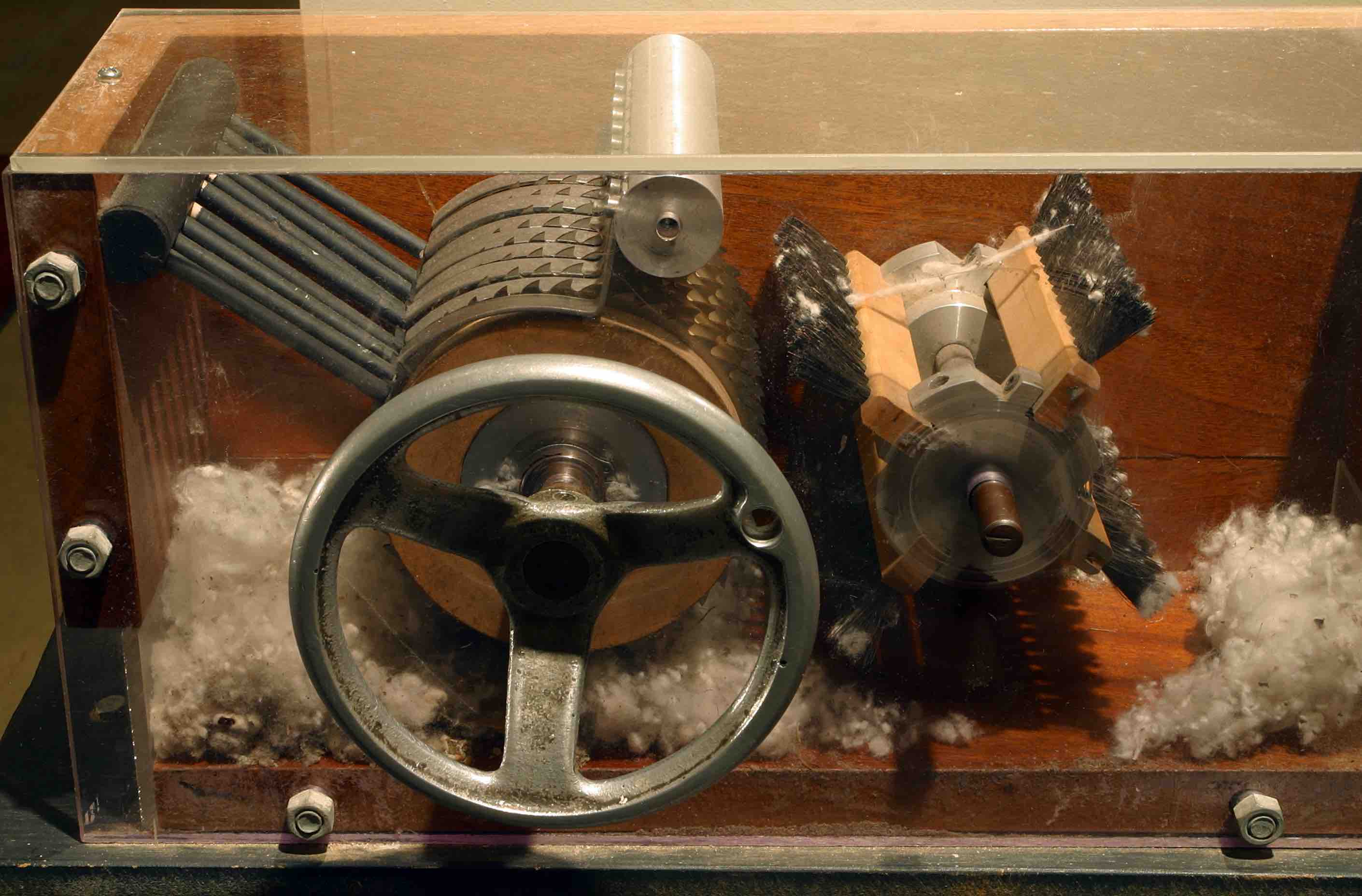

The game-changer came six years later, when Yale-educated inventor Eli Whitney built the first cotton gin (which is short for "cotton engine," and had nothing to do with liquor):

Long before Whitney came along, it had occurred to folks (including Washington) that cotton had potential as a replacement for Southern tobacco, especially since cotton plants require different nutrients than tobacco plants do, and so "tired soil" wouldn't be a problem. However, the type of cotton that will grow in the United States also has a large number of sticky seeds in the bolls. For every hour of picking cotton, it took roughly 10 hours to extract the seeds by hand. That cannot be made profitable, even with slave labor. The cotton gin resolved this; it could remove those seeds in just a few minutes. Thus was the slave economy saved, and set on the road to even greater prosperity than it enjoyed when tobacco was the primary crop.

The Incident: The aforementioned Haitian Revolution had an additional consequence for the United States beyond fueling slave owners' fear of a large-scale revolt. It also deprived France of its primary profit center in the New World, by a large margin, which made New France more a liability than an asset for First Consul of France (soon to be Emperor) Napoleon. And so, when the United States approached the Little Corporal about the possibility of purchasing the city of New Orleans (key to the international cotton trade, and thus the slave economy), he sold them the entirety of Louisiana at a bargain-basement price.

After the original 13 states formed a new country, the U.S. managed to add 9 more states without much difficulty, such that by 1819 there were 22 states in total, 11 with slavery and 11 without. When Missouri petitioned for statehood, not only would it be the 23rd state (an odd number, which matters a lot—keep that in mind), it would also be the first state to be carved entirely out of the Louisiana Purchase (Louisiana, though admitted before Missouri, was not made up entirely of land purchased from France). As Congress was taking up the matter, Rep. James Tallmadge (D-R, NY) proposed an amendment to the Missouri statehood bill that would have barred slavery within its borders.

Southerners were nowhere near as invested in their slave system by 1819 as they would be a generation or two later. However, they were still plenty invested in it. "You have kindled a fire which all the waters of the ocean cannot put out, which seas of blood can only extinguish!" thundered Thomas W. Cobb (D-R, GA) in response to Tallmadge's proposal. Cobb, and his fellow Southerners, had several reasons they deemed it essential that Missouri be admitted as a slave state:

- Whichever section got the "next" state would have a majority in the U.S. Senate. That is why Missouri being an

odd-numbered state was very significant.

- One of the most profitable things for slaveowners, besides selling cotton, was selling slaves to plantation owners

in newly formed slave states.

- Selling slaves westward was also perceived as a "release valve" that protected white Southerners from becoming outnumbered by their black laborers.

At the same time, Northerners in 1819 were nowhere near as hostile to slavery as they would be a generation or two later, though they were plenty hostile. "If a dissolution of the Union must take place, let it be so! If civil war, which gentlemen so much threaten, must come, I can only say, let it come!" Tallmadge threatened, in response to Cobb. Like the pro-slavery Southerners, anti-slavery Northerners also had numerous motivations that informed their point of view:

- They also wanted control of the Senate (which would have given them both houses of Congress, as the North already

had a large majority in the House). Many Northerners thought this only fair, as there were so many more of them, and as

the South largely controlled the other two branches of the government in the first half of the nineteenth century.

- Many Northerners believed that the future of the country was in free, white labor that would work hard on farms and

in factories. Generally speaking, two different systems of labor (free white and black slave) could not co-exist.

- Free people buy stuff, like the goods being manufactured in Northern factories. Slaves don't.

You will notice that we didn't write anything about the moral dimension of the debate. It is true that some Northerners, the abolitionists, opposed slavery solely on the basis that it was wicked and immoral. But these folks were a tiny minority in 1819-20, and would remain so throughout the antebellum era. There were certainly many Northerners who found slavery to be distasteful or wrongheaded, but while that problem would be paramount to 21st century Americans, it was secondary to economic and political concerns for most anti-slavery Northerners in the 19th century (including, most notably, Abraham Lincoln).

Congress tried to vote on Missouri statehood, and got nowhere each time, with various initiatives dying in the Senate. It did not take long before many folks concluded that the problem was intractable, and that there could be no solution that would satisfy both the North and the South. Thomas Jefferson, who was still around, and living in retirement in Virginia, famously observed: "[T]his momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union..." Other observers, North and South, shared this view.

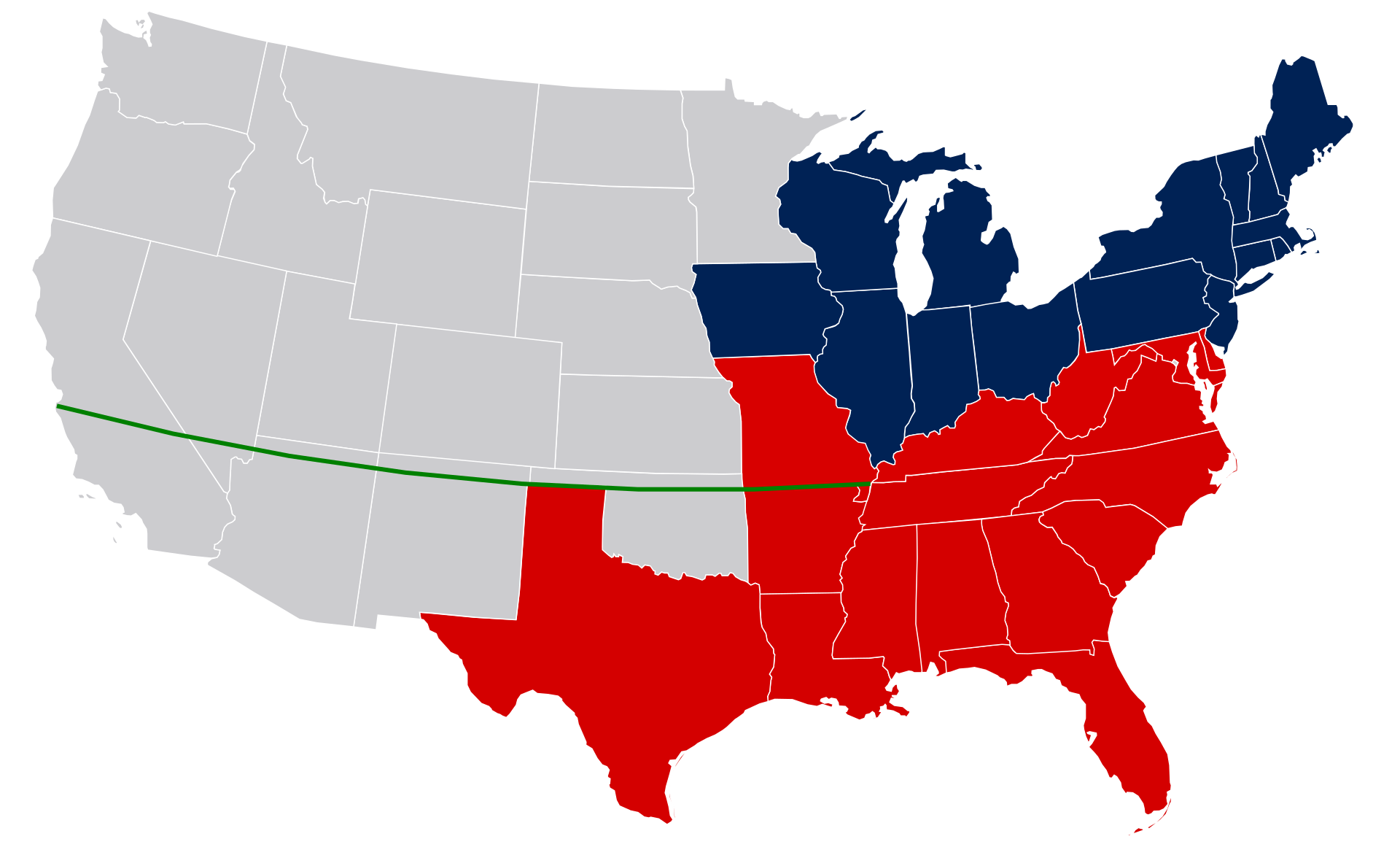

With things getting desperate, Speaker of the House Henry Clay (D-R, KY; later W-KY) stepped to the fore and showed off the skills that earned him the nickname "The Great Compromiser." Working with members of both the House and Senate, he was able to hammer out an agreement that had two explicit parts, and a third implicit part:

- Maine would be admitted as a free state, thus maintaining the free/slave balance, 12-12

- An imaginary line, extending from the Southern border of Missouri, would delineate future slave states from future free states:

- In the future, states would be admitted in pairs, one slave, and one free (this is the implicit part, and was not formally legislated)

These measures, which became known as the Missouri Compromise, were adopted by Congress in the early months of 1820. Technically, the whole matter took one year and two weeks to resolve, which means we nominally violated our rule above, but we're going to call it a rounding error.

Aftermath: In the short term, the crisis was averted, and the nation sang a chorus of kumbayah. The Missouri Compromise achieved near-sacred status thereafter, as both sides realized it was the only band-aid keeping the nation together.

Despite their public faces, though, partisans on both sides grew more and more entrenched in their positions, and began looking for any and every way possible to advance their sectional agendas. On top of that, there was a fair number of agnostics in both sections in 1819-20; over the course of the next four decades, the vast majority of those folks would become invested in the sectional strife.

You will notice that we excerpted the Thomas Jefferson quote above. Here is the rest of it:

[The crisis] is hushed indeed for the moment. but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.

It shouldn't be too hard to figure out when, and where, he was proven correct.

Up Next (on Thursday): California Statehood (1850). (Z)

Back to the main page