New Senate: DEM 49 GOP 51

New polls:

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Previous | Next

John McCain, 1936-2018

When John McCain announced on Friday that he was discontinuing treatment for the aggressive brain cancer he was diagnosed with about a year ago, it was clear that the end was near. On Saturday, less than 24 hours after going public with that news, and just days shy of his 82nd birthday, he succumbed to the disease. Now, as Edwin Stanton once observed, he belongs to the ages.

Yesterday, we covered what comes next, noting that Gov. Doug Ducey (R-AZ) is going to have a tough decision to make. He could go with a placeholder in Cindy McCain, or he could guarantee that Rep. Martha McSally (R-AZ) makes it to the Senate (but at the likely expense of Republican Jeff Flake's soon-to-be-open seat), or he could go with a fire-breathing conservative representative from a safely Republican House district (if such districts even exist right now). Whatever happens, the GOP's slender majority in the Senate will grow a little less slender. If Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) can hold his whole caucus together, that plus Vice President Mike Pence's tiebreaker vote makes for a majority. Of course, holding the whole caucus together is easier said than done.

McCain was a politician, a Republican, and a presidential candidate of the sort that we might not be seeing many more of in the near future. Specifically:

- Maverick: It's true that McCain's reputation as a rebel was

overstated, and that he was a loyal GOP soldier most of the time. In particular, he blew his biggest

chance to buck the system when he unleashed Sarah Palin (aka Donald Trump, v1.0) on the country,

instead of going with his gut and choosing independent (nee Democrat) Joe Lieberman as his 2008

running mate. However, it's also true that he was willing to go against his party on some pretty

high-profile issues on occasion, like his crucial vote to save Obamacare last year. His reward for

going against party orthodoxy, even if it was only rarely, was that many GOP voters (i.e., Trump's base) loathed

him as much as if he were a Democrat. This despite his long service to the GOP and the country, his

status as a war hero, and his personal integrity. If someone like that is not allowed to rise above

partisanship on occasion without vicious recrimination, then how can anyone—Democrat or

Republican—do so in today's hyper-polarized environment?

- Warrior-politician: There was a time when the sons of America's first

families were expected to respond to the call of duty, and to lay their lives on the line if their

country needed them to do so. In the 125 years after the Civil War, the United States has had 24

presidents, and 17 of them were veterans (about 70%). But then the Vietnam War happened, and with it

the nature of military service changed. If a person avoided service in that conflict, it was not

fatal to their political aspirations in the way that skipping out on the Civil War or World War II

would have been. Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump can all attest to that. McCain was

almost certainly the United States' last chance to elect a Vietnam vet, and so the nation will

presumably never be led by a soldier from that conflict. Meanwhile, the modern military is much

smaller than it once was, and draws far fewer highly-educated, well-connected folks of the sort who

tend to become politicians. Certainly, there are a handful of veterans in Congress or in statehouses

across the nation, but they are considerably rarer in politics than they once were (see below for a

possible exception, though). Consider that when McCain was launching his political career, 78% of Senators

and 72% of Representatives had military service on their resumes. Now those numbers are down to 6.5%

and 17%.

- Career Senator: McCain's 31-year Senate career overlapped with all of

the five longest-serving senators in U.S. history (Robert Byrd, Daniel Inouye, Strom Thurmond,

Ted Kennedy, and Pat Leahy). All of those men, along with McCain, were elected in a time when U.S.

Senators often became institutions and served for generations. But only Leahy is left from the list

above, and only three other Senators (Orrin Hatch, R-UT, Chuck Grassley, R-IA, and Mitch McConnell)

have been around longer than McCain. The pressure in Washington these days is brutal, and the

opportunities in the private sector are abundant. So, three- and four-decade Senators may well be an

endangered species from here on out.

- Institutionalist: When the Constitution was written, the Founding Parents intended the Senate to be roughly akin to the British House of Lords—more cautious, more deliberative, less prone to partisan pressure. McCain came of age when that tradition was still intact, and he internalized it. He generally preferred methodical deliberations and consensus-building, as illustrated by what are likely the three best-known actions of his Senate career: His co-sponsorship of the McCain-Feingold Act (which reformed campaign finance), his leadership of the "Gang of 14" (which temporarily salvaged the traditional methods of approving federal judges), and his Obamacare-saving vote (which was motivated primarily because of objections over process, and not policy). The antithesis to this way of thinking is Donald Trump, who cares little for caution, deliberation, or bipartisanship, which is a big part of the reason that McCain sparred with him. But, of course, Trump is not the only guilty party here. In today's Senate, the ends almost always justify the means, and when the Senate filibuster goes the way of the dodo (which will surely happen soon), essentially all vestiges of that body's commitment to proceeding methodically, making sure the minority party is heard, and building consensus will be gone.

Nobody can predict the future with perfect clarity, of course, but these are four dimensions of McCain's career that look like they're on their way to becoming anachronisms.

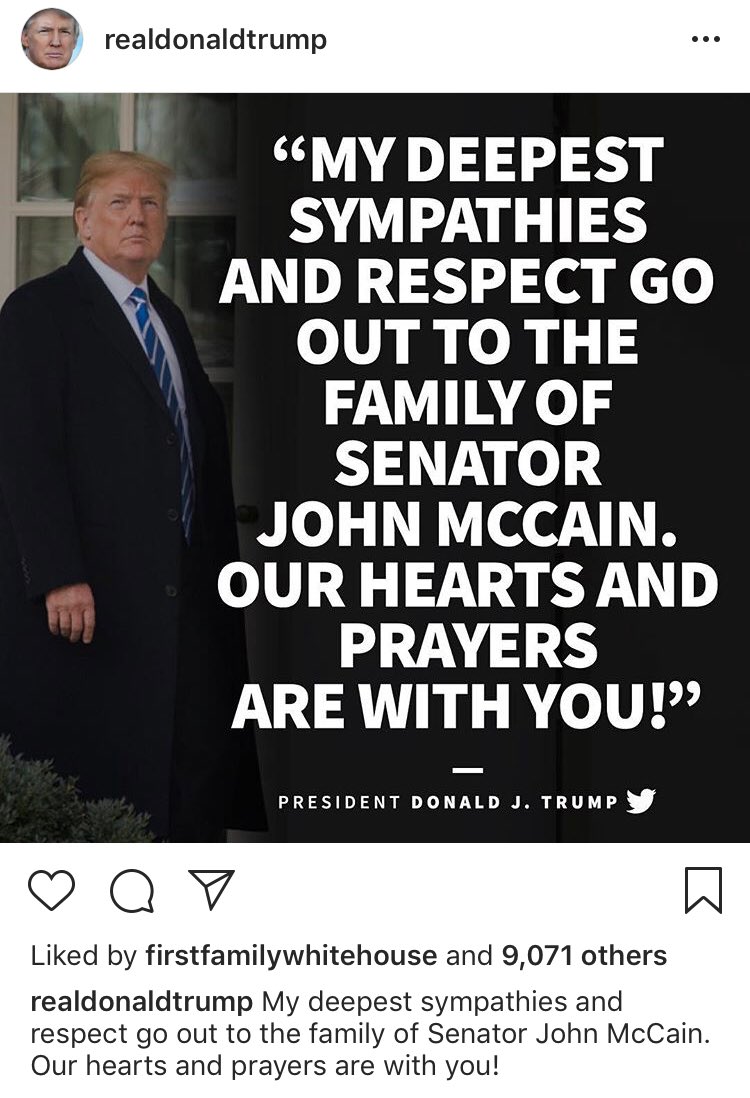

After news of the Senator's death broke, tributes to him came in from everyone who is anyone in American politics. That includes all of the living presidents, among them one Donald J. Trump. Here is the message posted to Trump's instagram account (his tweet had the same text, without the image):

The President is being absolutely lambasted for this, first because it doesn't actually honor McCain himself (only his family), second because the inclusion of Trump's picture comes off as kind of crass, and third because the "like" from the first family also comes off as kind of crass. In fairness to Trump, it's unlikely he had much to do with the tweet (it's not written in his style), and he certainly had nothing to do with the Instagram (unless he's been taking Photoshop classes). It's also probably the case that nothing Trump said or did would have avoided harsh criticism, given his wide unpopularity and his acrimonious relationship with the Senator. That said, it's also plain to see that all of Trump's predecessors did a better job of expressing their condolences:

Our statement on the passing of Senator John McCain: pic.twitter.com/3GBjNYxoj5

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) August 26, 2018

"Some lives are so vivid, it is difficult to imagine them ended. Some voices are so vibrant, it is hard to think of them stilled. John McCain was a man of deep conviction and a patriot of the highest order.” [...] Full statement by President George W. Bush https://t.co/FQVYWIUyGL pic.twitter.com/W8LCxJXRLi

— George W. Bush Presidential Center (@TheBushCenter) August 26, 2018

John McCain believed that every citizen has a responsibility to make something of the freedoms given by our Constitution, and from his heroic service in the Navy to his 35 years in Congress, he lived by his creed every day. https://t.co/946T7PnG53

— Bill Clinton (@BillClinton) August 26, 2018

Statement by former President @GeorgeHWBush on the passing of U.S. Senator John McCain of Arizona. pic.twitter.com/joT1reIihM

— Jim McGrath (@jgm41) August 26, 2018

STATEMENT BY FORMER U.S. PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER ON THE PASSING OF SENATOR JOHN MCCAIN pic.twitter.com/dcuUIJp8tK

— The Carter Center (@CarterCenter) August 26, 2018

McCain will lie in state in both Arizona and in Washington, and will—at his family's request—be eulogized by both Bush the son and Obama. His funerary rites are likely to occupy most of the headlines for the next few days which, ironically, figures to take a little bit of the heat off Trump for a while, as he reels from fortnight full of scandals. (Z)

DNC Changes Superdelegate Rules

This change has been rumored for months (and, on some level, since the 2016 Democratic convention concluded). On Saturday, however, it became official. In a near-unanimous vote, the members of the DNC decided that "superdelegates" (the 700-or-so people who are the Party's most prominent leaders) would no longer be allowed to vote on the convention's first ballot. Henceforth, only delegates won in primaries and caucuses will count in the first round of voting, and the superdelegates will cast ballots only if the proceedings move to a second (and third, and fourth, etc.) round.

In theory, the effect of this change is to reduce the power of the superdelegates to something of a tiebreaker vote, in the event that the convention features two evenly-matched candidates. In practice, the effect of the change is practically zero. The superdelegates have not swung a nominee since the system was introduced in 1984, and there's no particular reason to think they were going to do so in the future, since presidential nominations are rarely in doubt coming into the convention. Ultimately, the real point here was to throw a bone to the Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) wing of the party, where many folks remain persuaded (incorrectly) that the superdelegates cost their candidate the nomination in 2016. Actually, Clinton won because she got 3.7 million more popular votes than Sanders, and correspondingly more delegates. We shall see if the change salves their wounds, or if allowing any last vestige of the superdelegate system to linger will cause the angry feelings to linger, as well. As an aside, if the Republicans had had a large number of superdelegates in 2016, the GOP would probably have nominated Jeb Bush. (Z)

Federal Labor Unions 1, Trump 0

The great thing about executive orders, if you are the president, is that they are quick, and easy, and require no compromises with anyone. You have someone write it out (e.g., Stephen Miller), you put it in a handsome binder, you sign it, you post a pretty picture on the Internet, and you're done. The bad thing about executive orders, beyond the fact that the next guy or gal can erase them just as easily as you created them, is that their legal basis is a bit on the shaky side, since they are not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution (and weren't even made public, or numbered, until Abraham Lincoln came along). Consequently, federal judges are considerably more comfortable trampling on XOs than they are on, say, laws passed by Congress.

Donald Trump got an object lesson in this very point on Saturday. The President, whose hostility to organized labor dates back even to the days when he was a Democrat (and had to deal with construction unions), issued several orders in May limiting the rights of federal employees who belong to unions. One made it easier to fire "bad" employees, another placed limits on grievances, and a third unilaterally ordered the renegotiation of collectively-bargained contracts. The lawsuits were immediate, of course, and it did not take Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson long to rule. She struck down all three orders, writing that, "the president must be deemed to have exceeded his authority in issuing them." The Trump administration has yet to respond. That includes the President, whose time on Saturday was primarily occupied sending out many tweets about "Crooked Hillary" and her e-mails. (Z)

What Happens After Trump?

For some reason, this week's news has some folks wondering about what America will be like when Donald Trump leaves office. It's as if they think that time might be upon us sooner than we expected. Business Insider decided to ask a pair of historians, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, to weigh in on that question. They say that any of three basic scenarios is possible:

- Blip on the Radar: The first option, in brief, is that Trumpism is

utterly repudiated by the electorate and the Democrats re-take control of the government and undo

the worst consequences of his administration. Perhaps, if things go really well, the blue team (maybe

aided by some Republicans) is even able to fix some of the structural issues that allowed Trumpism

to flourish. Levitsky and Ziblatt think this is unlikely, however—particularly the latter

part.

- Fascism: This is not the exact word that Levitsky and Ziblatt use,

but it's what they are getting at with option two. Another possible future is one in which Trump

and his acolytes manipulate the system to keep populism and white supremacy in control of the

government for decades or generations, thus freezing out more than half of the electorate from

participation in their government.

- Hyperpartisanship: This is the scenario that Levitsky and Ziblatt think is most likely. They describe it as "democracy without solid guardrails." In essence, the Democrats eventually retake the government, and in tit-for-tat fashion, feel empowered to abuse their majority status just as the GOP and the Trump administration have done. Then, this will trigger a response from GOP voters, who will sweep away the Democrats, and the country will have another period of Republican abuses of power. Rinse and repeat, with the U.S. alternating between government only for Democratic voters and government only for Republican voters.

Levitsky and Ziblatt probably have the right of it in terms of the basic possibilities, but we're not so sure they are the best judges of which outcomes are most likely. First of all, the book they co-authored is When Democracies Die, which certainly suggests a predisposition toward the most negative outcomes. Further, while both scholars are brilliant and well respected, neither is an Americanist. Levitsky's speciality is actually Latin American history and Ziblatt's is European politics.

Fortunately, one of us (Z) just so happens to be an Americanist. And if we're looking for analogues to Trump, there are two that stand out—two occasions where white working people felt oppressed by the economic and political system, and so propelled a populist candidate to national prominence. The first is Andrew Jackson (who, of course, won the presidency) and the second is William Jennings Bryan (who didn't).

It's beyond the scope of this space to do a full comparison of the three men, so we'll just have to jump to the end of the story. In Jackson's case, he pursued policies that were quite Trump-like in the sense that they thrilled the base, but were rather shortsighted. The most obvious move of this sort that Jackson made was slapping tariffs on China, and starting a trade war...er, sorry, cutting the Second Bank of the United States at the knees. Killing the SBUS ultimately plunged the country into a vicious recession that began with the Panic of 1837 and weighed, of course, most heavily on the folks that had put Jackson in office. Nonetheless, the Age of Jackson triggered some important reforms in the American political system, designed to make sure the "little guy" (as he was conceived of in the antebellum era) got a voice: white male suffrage was made fully universal, parties became much more organized, political conventions were formalized, and newspapers that were accessible to the "common man" rose to prominence (starting with James Gordon Bennett's New York Herald, a staunchly Democratic paper first published in 1835).

Bryan, for his part, never really got much political power. Yes, he was Secretary of State for a couple of years in the 1910s, but an ineffectual one. Anyhow, because he was never president, it's a little harder to craft a "cause and effect" narrative with "The Great Commoner" as its linchpin. However, the abuses of the Gilded Age (1860s-early 1900s) were so great that they eventually became blindingly obvious to most voters, regardless of party. Bryan's three presidential campaigns certainly aided in that realization. And so, the early 20th century (aka the Progressive Era) witnessed some of the most important improvements in America's democracy in the last two centuries. The secret ballot became the norm (which meant voters no longer faced social pressure to vote a straight ticket), the people were given the power to elect their U.S. Senators (previously, the job was done by state legislatures), the civil service was reformed, and a host of other tweaks were made.

There are certainly some obvious reforms in the vein of the Progressives that modern-day Americans might pursue if the citizenry chooses to do so. For example, embracing the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which would nullify the increasingly problematic Electoral College. Or, adopting instant-runoff voting, which would allow citizens to cast a "protest" vote without de facto voting for the candidate they like least (Bonus: IRV was developed by the Australians, who were also the inspiration for the secret ballot 100 years ago). Another possibility is fixing some of the gaps in the Constitution that have clearly presented themselves, particularly as regards the handling of SCOTUS nominees, and of problematic conduct by the resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. And yet another option would be to do something to make sure votes are counted fairly and accurately, as opposed to leaving them exposed to possible equipment malfunctions or meddling from outside influences.

As we have already noted once in today's posting, nobody can predict the future. However, the historical record suggests that the U.S. tends to do a little better job of fixing the problems with its institutions than do the nations of Europe or Latin America. So, the level of pessimism demonstrated by Levitsky and Ziblatt is not quite justified. (Z)

This Week's Senate News

As noted last week, now that the 2018 campaign is in full swing, we're doing a weekly roundup of stories about the 35 Senate campaigns. Here is this week's installment:

- State Sen. Kevin de Leon (D-CA), like most challengers,

wants

lots of debates, and has proposed three of them. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), like most incumbents, would prefer not to give her opponent free publicity,

and favors zero.

- Susan Hutchison (R), who is apparently a little more ambitious than de Leon, has

demanded

10 debates with Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA). Presumably, the strategy here is to shame Cantwell into

"compromising" on three or four, since no politician is going to agree to (and no voter is going to watch)

10 debates.

- In Michigan, meanwhile, Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D) and challenger John James (R) have

compromised

on one debate, to be held right before the election.

- Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT), up for reelection in a state where most Democrats don't love guns, is

leading the charge

to stop federal funds from being used to arm teachers.

- Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL)

demanded

that the federal government release records relating to the collapse of a bridge at Florida International University

on March 15, which left six people dead. Nelson thinks that his challenger, Gov. Rick Scott (R-FL) bears at least

some responsibility for the accident, and wants to make sure that Florida voters think so, too.

- Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-HI)

announced

that she would not waste her time meeting with SCOTUS nominee Brett Kavanaugh, and advised Trump that he can,

in so many words, shove it. Stunts like this mean that instead of getting 63% of the vote, as she did last time,

she'll probably get 75% in deep blue Hawaii.

- Trying to curry favors with voters in a state that Donald Trump won by 19 points, Sen. Joe Donnelly (D-IN) is

running an ad

emphasizing how many times he's voted to support construction of the Mexican wall.

- Jim Newberger (R), who is trying to unseat Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) in one of the states most affected by global

warming,

declared

that climate change is real, but that it's the sun's fault, and there's nothing we can do about it. Scientists

disagree.

- By a large margin, Minnesota voters are more likely to

recognize

the name of Sen. Tina Smith (D) than of her opponent Karin Housley (R). Whether that is because Smith was lieutenant governor and is now

senator, while Housley is just a state legislator, or it is because Smith has the single most common last name in the country,

is not known.

- Josh Hawley (R), who is trying to knock off Sen. Claire McCaskill (D), took a bold step and came out

strongly

this week against Catholic priests who molest young children. There went the pro-child-molestation vote.

- Citizens of New Jersey are being

bombarded

with ads telling them that Sen. Bob Menendez (D) is corrupt (which is not necessarily incorrect). They're apparently working, as

his lead over challenger Bob Hugin (R) has dropped to 6 points (43%-37%).

- Mick Rich (R), who is trying to pull an upset in New Mexico,

lost

his campaign manager this week, who left to pursue "other opportunities." This reduced the businessman's full-time campaign

staff by 50%, down to one person.

- The campaign of Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND)

got caught

trying to sneak an ardent supporter into a town hall held by opponent Kevin Cramer. The woman in question,

whose name is Mary Rennich, was denied entry, and was presumably there to ask Cramer embarrassing questions.

- Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) officially

announced

he's a "no" vote on Brett Kavanaugh. That sort of party loyalty is a lot easier when you're up 15 points in the polls.

- If Corey Stewart (R) is going to pull off a massive upset of Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA), he'll have to do it

alone,

as other GOP politicians don't want to associate with a candidate who is himself known for associating with white

supremacists and neo-Nazis. Although maybe Stewart can get Donald Trump to come out for a rally or two.

- Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI)

announced

endorsements from 100 prominent business leaders in her state this week.

- While three GOP candidates bloody one another's noses on that side of the race, Rep. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) is

taking advantage of being unopposed, and is

running

Spanish-language ads on television.

- Donald Trump formally

endorsed

Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith (R-MS) this week. Given that she is a Republican, and her opponent is black, it is hard to imagine

who might have learned something new from this.

- Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) and her challenger, former governor Phil

Bredesen, are

sparring

over Blackburn's support for a 2017 drug enforcement bill. Blackburn says that she was trying to make sure

that people who legitimately need painkillers can get them without fear of prosecution, Bredesen says she's

in the pocket of Big Pharma, and that she's helped make it harder to crack down on opioid distributors.

- Rep. Beto O'Rourke (D-TX), who is trying to knock off Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), was

asked

about kneeling NFL players this week. O'Rourke's answer, in which he supported the right of protest and tried to put the kneeling

in historical context, was so good it went viral.

- Willard "Mitt" Romney, who knows he's got his election in the bag, is now trying to do what he can to save the other GOP members of Congress from Utah, like Rep. Mia Love.

And that's the way it is. (Z)

Democratic Presidential Candidate of the Week: William S. McRaven

For the second entry in our series of 2020 Democratic candidate profiles, we're going with a dark horse whose name has only been circulating for about a week:

- Name: William S. McRaven

- Age on January 20, 2021: 65 (his birthday is three days after the 2020 election)

- Background: A member of a military family, McRaven took his degree

in journalism at UT Austin and then immediately launched his naval career upon his graduation in 1977.

Over the course of 37 years, he was promoted all the way to full admiral, which is not common for

someone who did not graduate from Annapolis. He is best known for planning and overseeing the

operation that led to the death of Osama bin Laden. Since retiring, he has served as chancellor

at his alma mater, though he is stepping down this year.

- Political Experience: McRaven has never held political office. However,

he's held a number of high posts—U.S. Special Operations Command, Joint Special Operations Command,

and Special Operations Command Europe among them—that required significant political and administrative

skills, and that involved frequent interactions with high-level politicians.

- Signature Issue(s): Terrorism. He might be the United States' #1 expert in

practical techniques for reducing terrorist activity.

- Instructive Quote: "[President Trump], I would consider it an honor if

you would revoke my security clearance as well, so I can add my name to the list of men and women

who have spoken up against your presidency."

- Completely Trivial Fact: The Admiral's 2014

commencement speech

at UT Austin has been viewed nearly 7 million times on YouTube, and was turned into a bestselling book called

Make Your Bed.

- Recent News: Last week, McRaven wrote the scathing anti-Trump

op-ed

from which the above quote was taken. This is why he's now being mentioned as a possible presidential

candidate.

- Three Biggest Pros: (1) McRaven is the anti-Trump, not only in his op-eds, but also in

his demeanor, his military experience, and his methodical nature; (2) A decorated veteran, particularly one who helped

bring Osama bin Laden to justice, could appeal to moderates, independents, and disaffected Trump Republicans; and

(3) He's a very effective public speaker.

- Three Biggest Cons: (1) Is the country really interested in a second consecutive president

with no actual political experience?; (2) "Veteran president" sounds good on paper, but as John McCain and John Kerry both learned,

it doesn't seem to win presidential elections anymore; and (3) McRaven's tenure at UT Austin has gone poorly, raising questions

about his administrative abilities in a non-military context.

- Is He Actually Running?: So far, McRaven has given no indication that he plans

to throw his hat in the ring.

- Betting Odds: The bookmakers apparently don't follow the editorial pages,

since they're not yet offering odds on McRaven.

- The Bottom Line: It's hard to see how he lands the presidential nomination, especially since he hasn't been networking and fundraising for years the way that, say, Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Kamala Harris (D-CA) have. He could make a very interesting VP candidate, depending on who is at the top of the ticket. On the other hand, Ross Perot might have a few thoughts on the downsides of picking a navy admiral as your running mate.

The list of candidate profiles can be accessed by clicking on the 2020 Dem candidates link in the menu to the left of the map. (Z)

Back to the main page