George Elliott Morris, who took charge of FiveThirtyEight after the departure of Nate Silver, has taken a look at how good election polls are 8 months in advance. He starts out by noting that if the election were held today, there is no doubt that Donald Trump would win. However, the election is not being held today, and therein lies the rub.

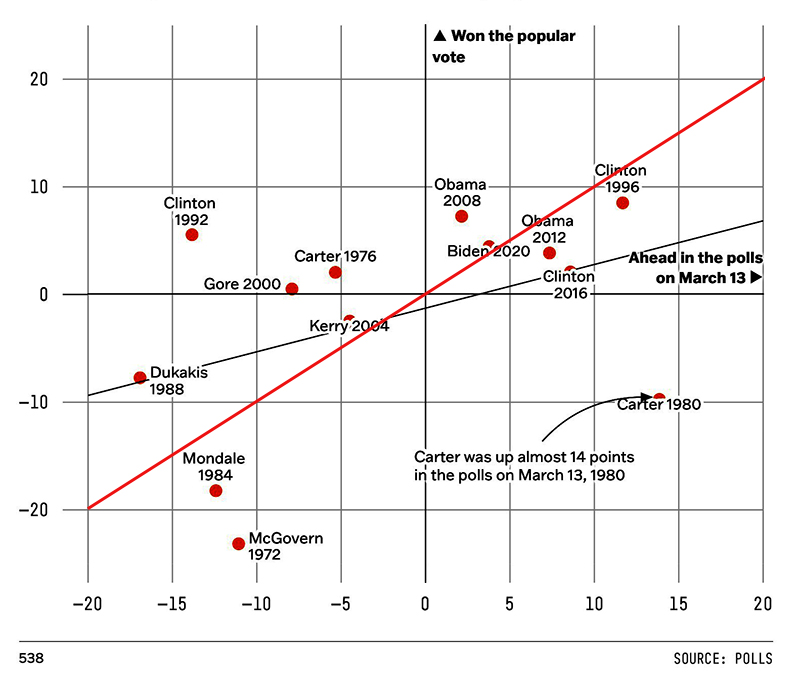

Historically, there have been years when polling this far out was terribly wrong. For example, at this point in 1980, Jimmy Carter was 14 points ahead of Ronald Reagan. Reagan won by 10 points, so the shift from March to November was 24 points. In 1992, the early polls were off by 19 points. In 2000, they were off by 8. This is not entirely surprising because stuff happens. Also, many voters really aren't paying attention this early. Here is a scatterplot of the early polls vs. the election result.

If the early polls were perfectly predictive of the final result, all the data points would lie along the red line. Some are above it, meaning the Democrat overperformed the early polls. Some are below it, meaning the Democrat underperformed the early polls. The ones in the second and fourth quadrants predicted the wrong horse would win.

Another thing Morris looked at is the average absolute value of the error. This far out it is about 8 points, with the state polls being a fraction of a point worse than the national polls.

However, a new consideration is the enormous polarization in the country. We will go out on a limb here and predict that the Republican will win the 2028 election... in Wyoming. For a vast number of voters, nothing will change their opinion, so states can be accurately predicted many years in advance, and 8 months is nothing. On the other hand, elections have become so close that getting it wrong by 2 points can be the difference between winning and losing.

A problem that all pollsters are facing now is nonresponse. A pollster may have to call 20 people to get one valid response. This drives up costs and makes pollsters more willing to use smaller samples and then force the sample population into the model of the electorate using statistics. But if the model of the electorate is wrong, the prediction will also be wrong. This effect is often around 3 points, so if the statistical margin of error is 4 points, the combined margin of error is 7 points. In close elections, this is enormous. Stating that Jones will beat Smith by 4±7 points is not enormously useful.

Still, most of the time the candidate leading in March ultimately won, even if the predicted margin was way off. That is a good sign for Donald Trump. But this year is so volatile, with a very long campaign, much action on the legal front, and two elderly candidates, that a lot can happen in the next 8 months. (V)