Previous | Next

New polls:

Dem pickups: PA

GOP pickups: (None)

DeSantis Tries to Attack the "Beer Problem"

It is widely said that many people vote for the candidate they would rather have a beer with. Or, probably more accurately, vote against the candidate they definitely would not want to have a beer with. Al Gore (2000), Mitt Romney (2012) and Hillary Clinton (2016) come to mind here.

One of the big, but as yet unspoken, problems Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) is going to have is the "beer problem." Policy aside, most people regarded George W. Bush as an easy-going, friendly guy, while Bill Clinton could charm the spots off a leopard. DeSantis comes off as cold, calculating, sneaky, and aggressive, not at all like Bush or Clinton. He is going to have to work on his likability issue. You can learn what you have to know about the federal deficit by reading some briefing paper a staffer writes for you. You can't learn how to make people like you by reading a briefing paper. In DeSantis' case, it is even worse because being aggressively nasty in order to "own the libs" is the core of his popularity with the base. It would be hard for anyone to appear to the base as a killer while making independents think you are warm and fuzzy. Not since Ronald Reagan has any presidential candidate come even close to pulling that off, and DeSantis certainly does not have the temperament or personality to make it work.

He apparently realizes he has a problem and is at least trying to do something about it. Whether he will succeed is something else again. The viability of his candidacy may depend on whether he can pull it off.

After his inauguration earlier this month, DeSantis held a dinner for donors who had given at least $25,000 to his campaign. It was catered by a fancy Italian restaurant that had just moved from New York to Miami (take that, blue state). During the dinner, DeSantis and his wife Casey (whose real first name is Jill) went from table to table saying hello to the donors. For any other politician in the country, this would be normal. For DeSantis, this was a huge breakthrough. He hates this kind of "retail politics," even with his own wealthy donors. He is much happier mapping out a plan to ship immigrants from Texas to Massachusetts to own the libs than he is meeting voters, even those clearly in his camp.

This tiny step toward DeSantis v2.0 is brand new and he sometimes can't remember how he is supposed to behave for even 24 hours. The evening after the inauguration dinner with the donors, he held a black-tie ball with other contributors. He couldn't be bothered letting them all have a photo with him. Last November, he flew to the Republican Jewish Coalition conference in Las Vegas, gave a speech, and flew home. He skipped the meet-and-greet part where potential donors could talk to him and size him up. At a recent meeting of the Republican Governors' Association, he gave his future stump speech. One of the attendees cracked that he didn't get to do both the question and answer part. One other donor said: "Ron is a little reserved and dry compared to George W. Bush and Bill Clinton." Even his own staff thinks forging connections with people is not his strength.

In 2016, Donald Trump broke and changed the rules. Until then, retail politics was crucial for candidates. They had to mix with the people, be seen eating all manner of ethnic foods, and engage in sports (or at least be seen jogging). The big question now is whether retail politics is gone forever or was Trump unique and everyone else has to go back to the old way of winning votes one at a time. In this context, it is worth noting that Pete Buttigieg came from nowhere to become one of the top Democratic candidates in 2020 because he met so many voters personally and they liked him. If retail politics is not dead, DeSantis needs to learn some new skills.

DeSantis' disdain for people holds not only for donors, but even for Republican politicians. When George W. Bush was reelected governor in 1998, at the National Governors' Association meeting in Feb. 1999, a dozen other Republican governors touted Bush for president, even before he announced a run. By contrast, Politico recently asked a plugged-in Republican governor if any current Republican governor will back DeSantis before his announcement, or even on the first day of his candidacy, and the answer was: "I don't think so." Another Republican governor reported that when someone asked him how to contact DeSantis, all he could do was go online and find the official home page for the governor of Florida. DeSantis doesn't even like hanging out with other Republican governors.

It is also noteworthy that not a single Republican governor showed up for DeSantis' inauguration, not even the Republican governors from adjacent states, Gov. Kay Ivey (R-AL) and Gov. Brian Kemp (R-GA). The governors may want to move on from Trump, but they don't like DeSantis. It's a far cry from 2000, when many Republican governors offered Bush their endorsements, strategists, donor networks, and control of their state parties early on.

It is still very early, but we can imagine a brutal Republican primary in which Trump and DeSantis fight over who is the meanist S.O.B and who can own the libs best, but if DeSantis wins that, he will have his work cut out for him trying to convince moderate Republicans, independents, and conservative Democrats that he'd be fun to have a beer with. (V)

Poll: Trump Is Crushing DeSantis in the GOP Primary

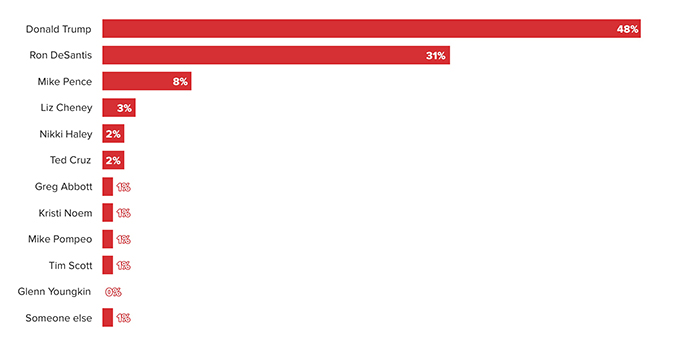

It's kind of early for horserace polls of Donald Trump vs. Ron DeSantis, but since pollsters are conducting them already, we might as well take a look at them, albeit with a substantial amount of salt. Morning Consult ran a poll of the GOP primary. Here are the results:

As you can see, Trump is at 48%, DeSantis is at 31%, Mike Pence is at 8%, and Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) is crying in his beer—alone, since nobody in their right mind would want to have a beer with him. Other polls have had other results in the past few months, but Morning Consult polls have been fairly consistent with results like this. FiveThirtyEight gives Morning Consult a "B" rating. If Gov. Kristi Noem (R-SD) wants the VP slot, she is going to have to do better than 1%, though.

Obviously, a lot can change in the next year. In particular, Trump is likely to be indicted in Georgia and maybe in D.C. That could convince some Republicans that DeSantis is a better bet, even if he is aloof and unfriendly. Among Trump voters, DeSantis is the clear second choice, so if something happens to Trump, DeSantis will pick up most of his supporters.

Republican voters have a favorable view of both Trump and DeSantis. Trump has 77% approve/23% disapprove and DeSantis has 69% approve/11% disapprove.

As to the general election, Joe Biden beats Trump 43% to 40% with 11% for someone else. Don't believe that. DeSantis beats Biden 44% to 41%, but this is before anyone has beaten on DeSantis real hard. It will be different once that happens. (V)

New York State Senate Committee Rejects Hochul's Choice for Chief Judge

Yesterday, the Judiciary Committee of the New York State Senate voted 10-2 to reject Gov. Kathy Hochul's (D) choice of Hector LaSalle to be the state's chief judge. Seven other members voted to send the nomination to the Senate floor without a recommendation. Adding these up, ten members do not want to send the nomination to the floor, while nine want the full Senate to vote on it, but only two of those nine actually support LaSalle. Put another way, that's 10 "nay," 2 "yea" and 7 "pass the buck" votes.

The New York judicial system is unlike that of any other state. First of all, the state Supreme Court is, well, not supreme. The top court is the (seven-member) Court of Appeals. It is headed by a chief judge. When there is a vacancy on the Court, the judicial nominating commission gives the governor a list of seven candidates. The governor must pick one of the seven for the nomination.

LaSalle is a Latino from a working-class background. Normally that would be good enough for most New York Democrats. However, LaSalle's voting record as a lower court judge suggests an anti-worker, anti-union, anti-choice perspective that the state senators don't like. Multiple unions oppose him as do pro-choice groups. Hochul was no doubt trying to score points with Latino voters by picking LaSalle, but he is too conservative for many of the state senators.

Hochul has threatened to take the state Senate to court to force an up-or-down vote on LaSalle. LaSalle might win a vote of the full Senate as all the Republicans would vote for him out of fear of a much more liberal candidate if he is rejected. What happens if Hochul does that and the Court of Appeals has to vote on its new chief judge? It would be messy. The legal aspect of this is murky. The state Constitution says that the governor gets to make appointments with the advice and consent of the Senate. Does this mean the Senate must take a vote on the floor, or can the relevant committee kill the nomination before it gets to the floor? It is uncharted waters. If this case ends up in the Court of Appeals, maybe Hochul could ask Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) to write an amicus brief since he has thought long and hard on the matter of whether a Senate must vote on a high court nominee.

There are potential national implications here. The New York State Legislature produced an extremely gerrymandered congressional map last year, but the Court of Appeals struck it down. Although a new map is required at least every 10 years, there is nothing to prevent the state legislature from drawing up a new map whenever it wants to. Some Democrats would like a more progressive chief judge than the one who retired so they can draw up a new map and get it in place before the 2024 U.S. House elections. That could conceivably result in two or three new House seats for the Democrats, so the matter of the chief judge is very important. (V)

Could Both Chambers of Congress Flip in 2024?

In all of U.S. history, it has never happened that the Democrats flipped one chamber of Congress at the same time the Republicans flipped the other one. But political analyst Stuart Rothenberg foresees that potentially happening in 2024. The reason is clear. The Republican hold on the House is extremely tenuous, especially if the Democrats can pick up two or three seats in New York. On the other hand, the Democrats have only a one-seat majority in the Senate and the map is brutal for them in 2024. So for different reasons, both chambers are at a real risk of flipping.

It has happened before that one party gains seats in one chamber and the other party gains seats in the other one. In fact, in 2022, the Democrats picked up a Senate seat while losing nine seats in the House. In 2020, Democrats gained three Senate seats while losing a dozen House seats. But actually having both chambers flip in opposite directions has never happened before.

On the Senate side, Sens. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), Joe Manchin (D-WV), and Jon Tester (D-MT) are up for reelection in deep red states. They all won in 2018, but that was when Democratic voters were motivated to stick it to then-President Donald Trump. They all are facing tough races this time and some of them could lose. Of course, if Trump is on the ballot in 2024, that could again motivate Democrats to vote, but Ohio, Montana, and West Virginia remain deep red states. The Democrats also have tough races in Michigan, Nevada, and Wisconsin. All the Republicans need to do is win two of those races. None of the Republicans up in 2024 are in any real danger. Not even the little-loved Ted Cruz.

As to the House, if the clowns take over and the House becomes a circus, it will be very easy for Democrats to make the case that control should be given back to them. Weeks of testimony about Hunter Biden's laptop, a forced debt crisis, the indictment of Rep. "George Santos" (R-NY), a successful motion to vacate the chair, and other things could be just enough for the Democrats to pick up five House seats, especially in a presidential year, when Democratic turnout is high.

Rothenberg is not going out on a limb and saying it will happen, but from where we stand now, it certainly seems plausible. Which party would a double flip favor? We think it would favor the Republicans because Democratic control of the Senate would allow a Democratic president to get administration officials and judges confirmed easily while it could block a Republican president from getting anyone the Senate didn't like from being confirmed. in other words, the Senate is more powerful than the House, so if you can pick one to control, pick the Senate. (V)

Select Committee Gave the Social Media Companies a Pass

The Select Committee turned over a lot of rocks and talked to a lot of people, but its focus never wavered from "whose fault was it" (Spoiler alert: The members concluded it was Donald Trump's fault). But although they had a lot of evidence on the subject, the Committee was reluctant to name another major contributor: social media companies. A 122-page memo circulated among Committee members delved into the roots of the violence and presented plenty of evidence that the failure of the social media companies to address online extremism was a big part of the problem. There was almost nothing in the final report about what they found due to a fear of angering the big, powerful companies.

The memo contained this text:

The sum of this is that alt-tech, fringe, and mainstream platforms were exploited in tandem by right-wing activists to bring American democracy to the brink of ruin. These platforms enabled the mobilization of extremists on smaller sites and whipped up conservative grievance on larger, more mainstream ones.

None of this sentiment appeared in the final report.

The Committee's own investigators discovered that employees at Twitter and other social media companies warned management about violent rhetoric on their platforms, but management didn't do anything for fear of offending conservatives. One former Twitter employee told the Committee: "Twitter was terrified of the backlash they would get if they followed their own rules and applied them to Donald Trump Only after Jan. 6, 2021, did they take some steps to rein in violent speech. And at Twitter, Chief Twit Elon Musk is busy undoing the small steps they took.

The effort to shield the big tech companies was bipartisan. Then-Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY) wanted to keep the focus entirely on Trump and saw everything else as a distraction. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), who represents a part of Northern California that includes Silicon Valley, didn't want to anger a large number of her constituents and donors, so she resisted having the final report put part of the blame on the social media companies. There was a bit here and there, but not a complete section or appendix on the subject.

The Committee's Purple Team spent a year going through tens of thousands of documents from multiple companies and interviewed numerous executives and employees from Facebook down to Gab and Discord. Yet its findings didn't make it into the final report, even though its memo showed how 15 social media sites played a big role in the events of Jan. 6. The Purple Team also showed how many platforms bent their own rules to avoid penalizing conservatives out of fear of reprisals. This is just the opposite of what conservatives say, that social media platforms is biased against them. In reality, the platforms allowed conservatives to repeatedly violate the rules without any punishment.

Since the final report was published, some of the evidence has come out in the transcripts. For example, Anika Collier Navroli, one of the longest-serving members of the Twitter safety team, described what happened when the #ExecuteMikePence hashtag started trending. She saw thousands of death threats and hateful messages and tried to remove them one by one. She said that she and a few other Twitter employees working with her for hours on Jan. 6 didn't stand a chance. The torrent of hate was too big. She faulted top executives for not blocking certain hashtags completely so that the tweets didn't have to be removed one by one.

When Post reporters called the social media companies to ask for comments, either they answered with "no comment" or recited their own published rules about hate speech, none of which they actually enforced.

Not pointing out the failure of the social media companies' role in fomenting violence may have consequences going forward. Both Texas and Florida have passed laws restricting what content social media companies can remove from their sites. Other states could follow, but it is not clear how any of them could enforce the law except for companies headquartered in their respective states. If Congress were to get involved, by contrast, it might do something based on its powers to regulate interstate commerce. But Congress apparently doesn't want to touch this hot potato. (V)

Small Donors Hate the Spam

Many people get an e-mail asking for a political donation for a candidate they like and make one, thinking that will be the end of it. Little do they know that they signed up for a lifetime of political spam. Some of them are discovering this and they do not like it one bit. Only a relatively small number of years ago, asking for money by text message or email was an innovation. Now people are overwhelmed with requests, so the rate of return is dropping precipitously. Candidates respond to that by asking more often, which reduces the rate of return even more. It is a vicious circle in the wrong direction.

Around 2000, campaign managers thought of raising small amounts of money from large numbers of donors as a way to counter large amounts of money from small numbers of donors. Campaigns sell or rent their donor lists, leading to more and more requests for money going to the same pool of people. In fact, fundraising has now outpaced everything else to become the primary form of voter contact. Even party activists are starting to complain about how many requests for money they are getting. Campaigns are so desperate for cash that they are starting to request it from independents and even members of the other party, which causes yields to drop even more. But because e-mail and text messages are so cheap, if even a fraction of one percent donate, it is a net win for the campaign—but a net loss for the people bombarded with requests. Despite the relatively low cost of text messages and emails, in 2022, fundraising was about 7.5% of total campaign spending, up from 6.7% in 2020.

The constant stream of requests is starting to be counterproductive. In one recent survey, a quarter of the respondents said that were not going to donate because they did not want to get on more lists and get even more requests. One strategist made the point that constantly bombarding people with messages they don't want and getting them angry is not a great formula for getting them to vote for you, which is the ultimate goal, after all.

One might think that the negative feedback from donors and the decreasing rate of return might cause campaigns to change tactics, but as long as a mass mailing turns a net profit, the incentive to continue will still be there. Some people have suggested that campaigns could stop asking for money five times a day and instead ask people to volunteer to go door knocking, do phone banking, put up yard signs, and other things.

There are two ways people can donate to a campaign and not get spammed forever after. One is go get a new e-mail address at Gmail, Yahoo, or elsewhere, like spamreceiver314159265@gmail.com. Use that only for giving donations to campaigns. If you need to verify it the first time you give, do so. Then ignore it except once every 6 months log in and delete all the messages without looking at them. The second way is to donate by mailing a check without putting a return address on the envelope. (V)

Missed It By That Much?, Part IV: Redistricting

Since the midterms, we've taken a look at some of the possible "but for [X]" factors that might have kept the House in Democratic hands. Here is a list of the first three of those items:

- Missed It By That Much?, Part I: New York Democrats Were Too Greedy

- Missed It By That Much?, Part II: House Retirements

- Missed It by That Much?, Part III: 6,670 Votes

Now, let's take a look at redistricting, which might be the most obvious "but for [X]" factor. When redistricting was finished after the 2020 census, Democrats were moaning that those mean people in Texas and Florida were going to steal the House from them by gerrymandering. Never mind that Illinois and Oregon did their best as well, and New York went overboard but a judge said: "Nope." So how did it work in the end? David Wasserman of the Cook Political Report has analyzed the results and come to a surprising conclusion.

First off, if the Republicans had not gerrymandered the maps in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Texas, Democrats wouldn't have lost the House and now-speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) would not have had to suffer the indignity of 15 ballots to get a job he probably won't be able to hold for all that long. However, to a large extent, the Democratic gerrymanders in Illinois, Nevada, New Mexico, and Oregon, plus the temporary court-ordered map in North Carolina, more than canceled that out. In fact, Wasserman concluded that the Democrats actually did better with the 2022 maps than they would have with the old (2012) maps.

Part of the reason is that the parties took different strategies to the gerrymandering table. The Republicans focused on making their incumbents safe, so for the most part, they made red districts even redder so none of their incumbents would lose. Democrats tried a much riskier strategy and drew as many districts as they could that were D+5 or even less. They had the advantage in those districts, but with a bit of bad luck, a weakly Democratic district is loseable. The gambit worked. Democrats won 24 of the 25 districts they drew for themselves in Illinois, Nevada, New Mexico, and Oregon, some of them by fewer than 5 points. If there had been a red wave, they could have lost all 25 of them instead of winning 24 of them.

To start with, Wasserman looked at the seven seats that stagnant states lost and fast-growing states got. The seven that disappeared were CA-47, IL-16, MI-02, NY-22, OH-16, PA-12, and WV-02. The first one had a Democrat sitting in it, but the other six vanished with a Republican sitting it in. The newly created districts were CO-08, FL-15, MT-01, NC-14, OR-06, TX-37, and TX-38. Democrats won four of those and Republicans won three. So the Republicans lost six seats from the old map and won three in the new map for a net loss of three. The Democrats lost one from the old map and won four in the new map, for a net gain of three.

Then Wasserman counted the districts that the Democrats wouldn't have flipped or held without redistricting. This was done using each district's pre- and post PVI scores, comparing the districts 2020 and 2022 results. For example, Texas Republicans made TX-15 4.4 points redder than it was, which is more than the 2.9 points by which Vicente Gonzalez (D) won it in 2020. Indeed, the district flipped from blue to red, as expected.

The conclusion of the study is that the Democrats won 14 seats they would have lost without redistricting and Republicans won 13 seats they wouldn't have won without redistricting. This is a net +1 for the Democrats. Throw in the +3 for the Democrats on account of seats moving among states, and it looks like the Democrats picked up four seats as a result of the redistricting process. So, the failure to hold the House is not due to gerrymandering because the Democrats did it, too, where they could. (V)

The 2024 Governors' Races

We recently discussed the three 2023 gubernatorial races, so now it is time to move on to 2024 since the races for governor are already gearing up. Eleven states will elect a governor in 2024. Nine currently have a Republican governor and two have a Democratic governor. Here they are in alphabetical order:

- Delaware (open): Gov. John Carney (D-DE) is term-limited, leading to an open seat race in

2024. The state is extremely blue and the Republican bench almost nonexistent, so the blue team will hold the seat. It's

just a matter of which Democrat wins the primary. Lt. Gov. Bethany Hall-Long (D) is a likely competitor, but so is AG

Kathy Jennings (D). At-large Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-DE) might give it a shot, but she can continue to get elected

to the House forever, so she probably will stay where she is. Solid Democratic.

- Indiana (open):

Another open seat here. Sen. Mike Braun (R) announced last month that he would rather be governor than senator, so he is retiring

from the Senate and will run for the open seat. He won't be the only one. Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch (R) is in and Eric Doden, a

wealthy venture capitalist is also in. The Democrats are going to be hard-pressed to find a candidate. Maybe Superintendent of

Public Instruction Jennifer McCormick might run, but she is a longshot. Solid Republican.

- Missouri (open): Another open seat due to a term-limited governor. Secretary of State Jay

Ashcroft (R) is almost certainly in, as is Lt. Gov. Mike Kehoe (R). A far-right candidate, state Sen. Bill Eigel (R),

might run, too. The primary could be bruising. Democrats don't really have a candidate. Solid Republican.

- Montana: Gov. Greg Gianforte (R-MT) is running for reelection. He is not going to get any

opponents. Ambitious Republicans are going to go after Sen. Jon Tester (D), who is more beatable, so Gianforte will get

another term, even if he beats up some more reporters. Solid Republican.

- New Hampshire: If Gov. Chris Sununu (R-NH) wants a fifth 2-year term, it is his for the

asking. However, if he decides 8 is enough (8 years, that is), the Democrats will have a very good pickup opportunity.

If Sununu calls it quits, former senator Kelly Ayotte (R) might run, as could failed senatorial candidate Don Bolduc (R).

There are others as well. On the Democratic side, either of the state's U.S. representatives, Annie Kuster or Chris

Pappas could run. Many other possible candidates are waiting in the wings for Sununu to make his move.

- North Carolina (open): Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC) is popular but term-limited. AG Josh Stein

(D) is already formally running for Cooper's job. He will probably win the primary without breaking a sweat. On the Republican

side, there is Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson (R-NC). He is a Black Trumpy Christian Nationalist who strongly supports gun

rights and opposes abortion. He also has a long history of making demeaning remarks about women, Jews, and LGBTQ people.

He's the whole package, if you like that kind of product. State Treasurer Dale Folwell (R) might run against Robinson.

If it is Robinson vs. Folwell in the GOP primary, count on lots of Democratic ratf**king. Hard to rate this race, since it depends so much

on the Republican nominee. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that North Carolina has had only three Republican governors

in the past 100 years, and only one (Pat "Bathroom Bill" McCrory) in the last 30 years..

- North Dakota: Billionaire Gov. Doug Burgum (R-ND) has already been elected governor

twice, but North Dakota does not have term limits. If he runs again, he's in like Flynn. If he decides to retire, there

are plenty of other Republicans who would be happy to take over his job. But first he has to decide. Solid Republican.

- Utah: Gov. Spencer Cox (R-UT) wants another term. He is a pragmatist and has criticized

Tucker Carlson. He's also a devout LDS Church member in a state where that matters quite a bit. His approval rating is

63%. He probably won't face any serious opposition from either party. Solid Republican.

- Vermont: Like New Hampshire, Vermont has a 2-year term for the governor. Like Sununu,

Gov. Phil Scott (R-VT) will have been governor for 8 years by Jan. 2025. He could win reelection easily if he runs, but

he might decide to call it quits. That would be an even better pick-up opportunity for the Democrats than New Hampshire.

If Scott stands down, all the other four statewide officers might jump in. One of them would probably win, since the

Republican bench is thin. Sure, some Republican state senator could run, but Scott was a very special candidate and

there aren't a lot of them around. It all depends on what he does.

- Washington: Washington does not have term limits, so if Gov. Jay Inslee (D-WA) decides he

wants a fourth term, he could probably get it. But he may decide that 12 years is enough. If Inslee retires, AG Bob

Ferguson (D) would be the most likely successor, but given how blue the state is, other Democrats might give it a shot,

too. It would take a very special Republican to win here; the last one to pull off the trick (John Spellman) took office

6 days before Ronald Reagan was first sworn in as president, and surely rode St. Ronnie's coattails a bit. Solid

Democratic.

- West Virginia (open): Gov. Jim Justice (R-WV), a coal billionaire and the richest person

in the state, is term-limited. He might decide to challenge Joe Manchin in a cataclysmic battle. Or he might ride off

into the sunset, which is bright orange due to all the coal dust in the air. Whatever he does, a Republican will almost certainly be elected governor. The only question is which

one. Secretary of State Mac Warner (R) is in. Also, two legacy candidates: state Del. Arch Moore Capito, son of Sen.

Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV) and grandson of former governor and convicted felon Arch Moore, as well as auto dealer Chris

Miller, son of Rep. Carol Miller (R-WV). The only Democrat who might make a race of it is... Manchin, who has made at

least a little noise about getting his old job back (he was governor from 2005-10). But he's unlikely to jump in, and

would likely be an underdog even if he did, as his popularity isn't too high right now. Solid Republican.

For the most part, few governor's mansions are likely to flip to the other party. The only ones that might do so are New Hampshire and Vermont, and they will only flip if the current governor retires. Otherwise, no states are likely to swap a Democratic governor for a Republican one, or vice versa. (V)

Looking Backward: How Did the Readers Do?, Part II: Right-Wing Politicians and Media

Another entry as we take a look at how impressive the readers' (crystal) balls are. One can only hope that today's batting average is better than the one from the Trump predictions.

- D.R. in Old Harbor, AK: The Dominion lawsuit will loom over Fox and other right-wing

media. This will impact the midterm elections in the Democrats' favor.

Boldness: 2.5/5. Certainly possible, but this is broad enough that there are many ways it could come true. That's going to cost some boldness points.

Final Score: 2 (Accuracy: 2, Boldness: 0). This one is very hard to judge. Certainly, the Dominion lawsuit is looming, so we'll give credit for that. But did it affect the midterms? Maybe, but there's no way to be sure. The most obvious impact would be in how Fox, et al. choose not to cover the news. And without inside information, we can't know what those decisions were, much less if they had a meaningful impact. - J.I. in San Francisco, CA: Various lawsuits against Fox, OANN, etc. will result in at

least one of these outlets having to shut down, and the others will have to tone down their style, further alienating

whatever audience they still have. At least one of these networks' major hosts will leave for a Q-flavored online

platform.

Boldness: 5/5. This is most certainly not the way things are trending now, since the cable networks are currently in a race to the right fringe, while Q seems to be ebbing. So if this is right, it will be quite the prediction.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). OANN is on life support, but it's not dead yet. And the others are still chugging along nicely. - N.S. in Milwaukee, WI: In Wisconsin, Governor Tony Evers (D) will win by only a few

hundred votes, with Republicans disputing thousands of votes from Milwaukee. The mainstream media will frame the result

as inconclusive, and the right-wing media will frame it as clear evidence of fraud, causing armed right-wingers to

mobilize from around the country and march on Madison. A standoff with the National Guard will ensue, and right-wingers

will consider it a training exercise for the 2024 election.

Boldness: 5/5. There is so much in the way of specifics here that full boldness points will be earned if it all comes to pass.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). Evers won fairly comfortably, by modern standards, 51.2% to 47.8%. - A.C. in Columbus, OH: The worst domestic terrorist attack in American history will take

place, surpassing the Oklahoma City bombing. More than 250+ will be killed and many more wounded. As a result of this,

Joe Biden's approval rating will skyrocket, just like George W. Bush after 9/11, because if there's one thing Joe does

well, it's empathy. Further, it will be revealed the terrorist was directly inspired to act based on inflammatory

rhetoric from right-wing media, and it will spark a serious national debate about the extreme partisanship of the media

and how and if speech of "journalists" should be limited if it is: (1) knowingly and demonstrably false and (2) could be

seen as incitement or otherwise presenting a clear and present danger.

Boldness: 5/5. Again, it's so specific that if it comes to pass, full boldness points.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). Did not happen, thank goodness. Incidentally, while this is a perfectly valid prediction, we decided last year that we don't want to be in the business of predicting large-scale and/or violent death. So, we are not going to run predictions in this vein going forward. - J.F. in Fort Worth, TX: The disastrous 2022 midterms will usher many new Republicans into

Congress, almost all of whom will make Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and Lauren Boebert (R-CO) seem reserved and

intellectual in comparison.

Boldness: 5/5. We think this is pretty unlikely. First, the ultra-right districts, the kinds that produce Greenes and Boeberts, already have sitting representatives. Second, we almost cannot conceive of someone who makes that duo seem reserved and intellectual. Well, unless Mike Lindell gets elected to the House.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). There were a few nutters elected this cycle, but we've seen no evidence they are nuttier than Greene, Boebert, etc. Now, if you had written "someone who makes that duo seem ethical and honest," then we would have given you points due to the election of Rep. "George Santos" (R-NY). - S.B. in New Castle, DE: The fringe conservatives will move beyond Trump and begin to

coalesce around another man who is more politically savvy in messaging to a broader audience.

Boldness: 3.5/5. Maybe, but Donald Trump is like the comic cat Garfield in numerous ways. And one of those is that he seems to have nine lives. So, we think this is fairly bold.

Final Score: 8.5 (A: 5, B: 3.5). We think this is on the mark. It's true that the base is still on board the S.S. Trump, but a lot of the fringy, outspoken types have transferred to the S.S. DeSantis.

- K.E. in San Bernardino, CA: Due to his handling of coronavirus resurgences, Gov. Ron

DeSantis (R-FL) will lose re-election.

Boldness: 3.5/5. Given his record and Florida's relatively even partisan split, it could happen. But it's the less likely outcome.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). Nope. He easily beat Crist. And given how loyal Florida Republicans seem to be, he might well have beaten Christ, had he been on the ballot. - S.N. in Santa Clara, CA: Many Republican states passed election laws to allow the

legislature, the state elections office, or some other designated entity to review and change the results of an

election. At least one state will use their law to try and change an election outcome in 2022.

Boldness: 3/5. They are certainly plotting, planning, and scheming—often openly. But this is not going to be easy to execute. We'll have some commentary on that matter soon.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). There was shockingly little of this sort of thing in 2022. - A.B. in Wendell, NC: GOP chicanery will cost Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) his seat.

Boldness: 4/5. This is a more specific version of the previous prediction, we would say, and so deserves a little more boldness credit.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). Actually, it was the opposite. Republican tomfoolery (i.e., nominating Herschel Walker) saved Warnock's seat. - W.V. in Hemet, CA: Some Republicans will flip on immigration... after the midterms, due to

the basic pressure on the U.S. economy: not enough workers.

Boldness: 4/5. It could happen, but it would be a major repudiation of Trumpism.

Final Score: 0 (A: 0, B: 0). This hasn't happened. It still could, we suppose, but it hasn't yet.

By our count, that's 10.5/120, for a batting average of .087. The running tally is 23.5/240, for a running batting average of .097. That's not even good enough to make the Pirates, though the Oakland A's remain a possibility. Some categories are easier to predict than others, so we expect that average to improve next week. (Z)

Previous | Next

Back to the main page