This was a relatively low-news week, and when that's the case, the questions are more diverse. Although not in the sense discussed in the question by A.G. in Los Angeles.

M.M. on Bainbridge Island, WA, asks: As we all have heard, Mike Pence is seeking protection under the "speech and debate" clause of the constitution to avoid testifying to Jack Smith's grand jury. When news of this subpoena was made public, Donald Trump said he would use executive privilege to prevent that testimony, a claim I haven't heard again since Pence announced his plan.

(One of) my questions is whether, once the former VP takes his case to the Supreme Court and loses, Trump can then make HIS claim and take that to SCOTUS? And speaking of appeals to that court, do you think Mark Meadows will take his claim of executive privilege all the way there? If so, that's three cases potentially being appealed to the Supreme Court, which could push any further action until next summer at least (by which time it would be too late to try a case against Trump). How do you see this working out for them? Do you think they are coordinating the substance and timing of their appeals? I wouldn't put anything past those three crooks.(V) & (Z) answer: To start, Trump can blather all he wants, but he has nothing to do with the testimony of Pence and/or Meadows, as he has zero standing here. The sitting president, namely Joe Biden, might be able to block testimony of a former executive officer on the basis of executive privilege. But not a former president.

And Meadows and Pence will undoubtedly take their case as far as they can, but they are not going to be able to buy all that much time. The courts aren't stupid, and know an effort to game the system when they see one. And the legal issues here are simple and have already been litigated. So, the cases will get fast-tracked, and will be resolved by this summer, at the latest (and probably more like this spring). And the resolution will be that neither Pence nor Meadows has a legal leg to stand on.

D.E. in Lancaster, PA, asks: The reason why Judge Robert C. McBurney redacted the rest of the special grand jury report was to protect the due process of those persons named in the report. So, is it logical to assume that, for the individuals whose due process the judge is protecting, the special grand jury made recommendations to charge these individuals with some unnamed crime? Is there any way we are getting worked up for something that will turn out to be the Mueller Report, Part Two?

Also, I seemed to remember Fulton County DA Fani Willis opposed revealing this report due to imminent charging decisions. For me, at least, "imminent" means "pretty freaking soon." So what's holding this decision up? Could Willis be conferring in any way with AG Merrick Garland and/or Special Counsel Jack Smith about her intentions?(V) & (Z) answer: We think that's the only possible way to interpret the redactions. After all, if the report says "Donald Trump is innocent of any wrongdoing," then there's no due process to be protected and there is no reason that could not be released.

Also, keep in mind that the Mueller Report had damning information in it, and also (de facto) recommended prosecution. The reason that nothing came of it is that the people making prosecutorial decisions (e.g., Bill Barr) did not want to indict, for various reasons. But that does not apply here; Willis is not in the bag for Trump and his underlings, and there is no DoJ "guidance" that forbids the indictment of former presidents.

As to the delay, only Willis and her team know. We will likely find out eventually exactly what i's she is dotting and what t's she is crossing right now, but until then, we wait.

And it's unlikely that Willis is chatting with Garland/Smith, at least about strategic matters (they might be sharing evidence, though). It would be unethical, and would certainly trigger a scandal if it came out that was going on.

R.R. in Nashville, TN, asks: DiFi had another "incident" yesterday. So what happens if she does resign or vacates early? Who gets picked? How does that affect the race for the U.S. Senate seat? Does it simply add another person to the already crowded field, or will the person chosen be a true caretaker?

(V) & (Z) answer: California is one of 35 states that allows the governor to choose a replacement senator without any restrictions on the person chosen. So, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) would pick Feinstein's replacement, and that person would serve until the next general election (Nov. 2024).

Newsom has already said that, if he has to make a pick, it will be a Black woman. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA) was the odds-on favorite, but that was partly because she was expected to be a caretaker. Now that she's expressed interest in a longer-term arrangement, Newsom probably won't tap her, as he does not want to appear to be playing favorites in the 2024 election. At this point, the most likely placeholder pick would be the 84-year-old Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA).

R.V. in Pittsburgh, PA, asks: If, for health reasons, Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA) were to step down, does Pennsylvania still have the special election in the same year as the vacancy? In April 1991, Sen. John Heinz (R-PA) was killed in a plane crash. There was a special election that year in November.

Is that still the way in works in Pennsylvania for special elections?(V) & (Z) answer: Pennsylvania follows the same rules California does (see above), which means that Gov. Josh Shapiro (D-PA) would choose a replacement for Fetterman, and could choose anyone he wished. That person would serve until November of 2024, unless they won election in their own right.

Obviously, the rules have changed since 1991. Back then, Pennsylvania law required that a special election be held to fill a vacant Senate seat. Today, however, only 13 states (most of them smallish states) call special elections if a senator dies because special elections are very expensive.

J.K. in St. Paul, MN, asks: Why is the government using $500,000 missiles to shoot down balloons?

I get that the pilot can't lean out the jet window and puncture it with a pair of scissors, but it would seem a couple of bullets would be cheaper, safer, and less destructive to the whole contraption.(V) & (Z) answer: It is because balloons, when punctured, tend to explode. And it's not great for a pilot to have an explosion take place right in their flight path, that they have to either fly through or take aggressive steps to avoid. So, it is best to shoot the balloon from a distance of about 10 miles. But, at 10 miles away, they are a pretty small target. And that being the case, a Sidewinder is far and away the best tool for scoring a hit.

It's true that half a million bucks is a lot for a missile. But if something happened, and a pilot had to eject, well, an F-22 costs about $200 million.

B.B. in St. Louis, MO, asks: Which cost more: The Chinese spy balloon or the sidewinder missile used to shoot it down?

(V) & (Z) answer: The Biden administration is keeping details about the equipment on the balloon close to the vest. So, there is no way to know for sure. However, the balloon did have high-tech listening, recording, and broadcast equipment, including some very-high-end antennas that are visible in photographs. Odds are, the balloon cost more than $500,000.

A.G. in Los Angeles, CA, asks: You wrote that Joe Biden was emphasizing diversity in appointing judges. Specifically, of 100 judges he's seated, 76 are women and 68 are people of color. The general point of diversity is to have elected/appointed officials match the electorate (at least, that's what everyone is told). With the U.S. being 71% white and male/female split being roughly 50/50, this does not really match the electorate. The argument that white men have an outsized majority in the judiciary would make sense and the hires are bringing the judiciary more in line with reality, but that is not what you wrote.

Diversity through the lens of black/white, male/female is somewhat pointless. It basically says any black human being is completely different from a white human being, or conversely that all black/white/male/female people are basically the same. There seems to be a distinct lack of interest in hiring people who have very diverse life experiences. A white woman who grew up in a wealthy suburb is looked upon the same as a white woman born in Africa who moved to the U.S. for college, despite there being a huge difference in their life experiences.

How would you define diversity, and how would you measure if an organization is diverse or not?(V) & (Z) answer: We can only say a few things in response. First, the bench appointments of Donald Trump were overwhelmingly white and male, while the appointments of George W. Bush skewed that way (although not overwhelmingly so). Consequently, the appointments of Biden have to be overwhelmingly not white and male in order to make the judiciary look more like the electorate. We thought this was understood, and that we did not need to spell it out.

Second, the U.S. decided long ago that "diversity" primarily means racial and gender diversity. Maybe a little attention, in some contexts, is given to things like religious diversity, or diversity of sexual orientations or gender identities, but not a lot of attention. And there is basically no attention given to things like diversity of life experiences, class diversity, or diversity of political opinions.

Third, the assumption underlying diversity-based initiatives is that it works at the macro level rather than the micro level. That is to say, an individual hiring decision or an individual school admission might very well end up favoring a wealthy Black woman over a poor white male with a compelling life story. However, hundreds or thousands of such decisions are understood to be corrective of historical inequities, on the whole.

Fourth, and finally, people far more qualified than we are have wrestled with these issues, and this is the system that resulted. Even if we can see some of the problems with the system, we haven't the faintest idea what would be better.

J.L. in Mount Vista, WA, asks: You wrote that Republican voters now demand "economic populism." What is that?

I had always assumed that politicians like Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) were economic populists because they advocate for consumer protections and they do battle against the abuses of large corporations and unfair global trade agreements. Is this what Republicans now want? Or do I have the wrong idea of what "economic populism" is?(V) & (Z) answer: Well, populism means "for the people." And so, economic populism means something like "making the economy work better for the people," which implicitly means making the economy work less well for business interests.

So, in a broad sense, the Senators certainly are economic populists. In fact, in his lecture on the Populists and the Progressives, (Z) does a brief bit where he shows that searching Google for "Bernie Sanders populist" generates hundreds of thousands of hits and searching for "Bernie Sanders progressive" also generates hundreds of thousands of hits. That said, the Warren-Sanders version of populism is definitely the more refined version favored by the original Progressive Movement. That is to say, working within the system in order to try to correct its inequities.

By contrast, the original Populist Movement was very much interested in fundamentally rebooting the U.S. economic system, or even burning it down. Their key plank was the issuance of a vast amount of silver-backed currency, which would have had a hyperinflationary effect and might well have crashed the U.S. economy. Today, Republicans who are talking about things like defaulting on the debt are embracing the same basic risk.

Note, incidentally, that Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) is most certainly not an economic populist. He's a greedy plutocrat who is willing to do enormous damage to the country so that he and his wealthy friends and backers can keep more of their money. In other words, not all radical economic proposals are populist.

A.B. in Wendell, NC, asks: You outlined the four "mini-parties" that exist within the Democratic Party, and named some names from each group.

I am curious where you would place a particular congressman... one who used to be my congressman, and for whom I worked to get re-elected several times, and once even moved to remain in his district when lines were redrawn

He was famous for telling me, when I asked him about certain legislation: "Look, I am on your side on this one, but that dog won't hunt in the House." This was his way of telling me that if what I wanted came up, he'd vote as I would like... but no way was he going to co-sponsor it.

I'm wondering which mini-party you think he fits in. I know which one I think... but I want your take. I am speaking of Congressman Lloyd Doggett (D-TX)(V) & (Z) answer: Obviously, the vast majority of Southern Democrats who hold political office are centrist firebrands, because that's the only way they can get elected. The only common exceptions to that are members who represent majority-Black constituencies (and who are often Black themselves) and members who represent very large cities.

That said, there are occasional Southern Democrats who aren't in one of those two categories, and who are nonetheless considerably more liberal than most of their colleagues. Senator and Representative Claude Pepper was one, Lyndon Johnson was another, and Doggett is a third.

We also noted in that piece that "individual members sometimes move between groups." We think that's the strategy that describes Johnson and Doggett, in particular. Their public statements, and sometimes their votes, would be characteristics of centrist firebrands. But their personal feelings, and sometimes their votes, put them more in the progressive establishment category. As Johnson himself said, on multiple occasions: "I'm a lot more liberal than my voting record."

Pepper, incidentally, didn't play the game the way Johnson did and Doggett does, because he just didn't give a sh** about kowtowing to those politicians and voters who were to his right. The trade-off for that, though, is that he went from being a senator (1936-51) to being a representative (1963-89). That's not the usual career progression.

J.F. in Ft. Worth, TX, asks: (V) wrote that the "Progressive Insurgents" in the House are "way out on the edge," policy-wise. But it's my understanding that a lot of their proposals (raising the minimum wage, universal health care, more expansive laws to curb climate change, etc.) are favored by a majority of Americans and sometimes a large majority. If this is the case, how can they be described as "on the edge"? Is this an indication that the Democratic party leadership really is out of touch with what Americans want and is, indeed, too timid?

(V) & (Z) answer: Note that "on the edge" does not mean "radical," necessarily. People who are true radicals don't get elected to political office, generally speaking. In this case, "on the edge" just means "farthest left in terms of their policy positions." After all, someone has to be on the edge.

And you are right that there is majority support for a lot of things that The Squad advocates for. However, American voters are a curious lot, and they often don't vote for the things they claim to support. Sometimes this is because of tribalism (e.g., all the people who favored the Affordable Care Act but opposed Obamacare, despite those being the same thing). Sometimes this is because of fear of change. Sometimes this is because other things take priority (e.g., the Second Amendment is more important than global warming).

There is also the small problem of the U.S. Senate, where you have to have 60 votes to get things done, and where small, less populous states wield a disproportionate amount of power. And that is before we get into the fact that some senators are doing the bidding of the donor class, and not necessarily the bidding of their constituents. Add it up, and even policy planks that are very popular (say, 70% support) still have a tough hill to climb once they get to the Senate. This being the case, we think the Democrats squeezed about as much legislation out of their 2-year paper-thin majority as was possible, and we do not think they have been too timid.

M.P. in Ft. Worth, TX, asks: What's going on with Sen. Mitt Romney's (R-UT) moves lately? First, he dresses down Rep. "George Santos" (R-NY) in a very public and conspicuous manner at the SOTU. Then, Romney follows that up by commending President Biden's response to the spy balloon. Might Willard be teasing a run for the White House, making a play for the "sane" lane? He's got experience as governor. He didn't do all that poorly in a national race against an incumbent president. He can self-finance, at least at first. He doesn't have enough life clock left to become a Senate kingmaker but, on the other hand, running deep into your septuagenarian years is apparently no longer disqualifying. Could he find traction (or at least serve as Trump spoiler) in a way Nikki Haley or the Mikes might not?

(V) & (Z) answer: If Romney is thinking along these lines, then he's delusional. The problem is that he's left himself in political no man's land, at least when it comes to national politics.

In the Republican primaries, a would-be GOP candidate has to get at least some of the Trumpers. Dominating the sane Republicans just isn't enough. And thanks to the impeachment votes alone (not to mention other apostasies), Romney isn't going to get any Trumpers at all. Also not helping is that the Trumpers are mostly evangelicals, and evangelicals look askance at LDS Church members.

And then, if Romney did somehow survive to the general, he's blown his centrist credibility with independent and Democratic voters. Just picking Paul Ryan was enough to wipe out all the reaching across the aisle he did while governor of Massachusetts. Add in "binders full of women," and snotty remarks about how the rich people are carrying the rest of American society, and that horrible photo of him kissing up to Trump and some of his votes for Trumpy policies, and there's just no crossover appeal there anymore.

All of this said, we don't think Romney is making a play for the Republican nomination. More likely is that he sees the end of his career is nearing, and he wants to leave the arena with, as much as possible, a reputation as a wise elder statesman. Think late-career Hubert Humphrey or late-career Adlai Stevenson (the son, not the father).

M.H. in Bellingham, WA, asks: In the item "What about Brian?," you described a scenario that had Georgia governor Brian Kemp (R) launching a presidential run in 2028, but not before. Do you think Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger's (R) endorsing an earlier Georgian primary for 2028 (and not 2024) is deliberately part of that scenario—a way to get Kemp out ahead of the pack with an early victory in his home state?

(V) & (Z) answer: We think Raffensperger is telling the truth—it's too late in the cycle to start rewriting the 2024 calendar, and he doesn't want to try.

As to 2028, Raffensperger likely thinks that putting Georgia earlier in the queue is a good thing overall, as it gives the state greater importance. He probably also sees that it would help Kemp out, and views that as a good thing as well, as the Secretary seems to like his (nominal) boss. Undoubtedly, it also has not escaped Raffensperger's attention that if he remains close with Kemp, and Kemp launches a presidential campaign that gains any traction at all, that is likely to help the Secretary get a promotion to governor.

M.G. in Boulder, CO, asks: You wrote: "In short, while there is a huge amount of attention to who will be the nominees, keep in mind that it is the Electoral College that matters and the patterns there tend to transcend who the candidates are."

From this, I am making the assumption that you both think the Electoral College will remain part of our system even though it has twice recently denied the presidency to the winner of the popular vote and even though I get daily e-mails telling me it's outdated, unnecessary, and unbalanced, giving too much weight to the shrinking rural population. Why do you think it will stay and when, if ever, do you think it will go?(V) & (Z) answer: People have been calling for an end to the Electoral College since at least 1876. It's still here, and the smart money says it will be here long beyond the lifespan of anyone who is currently reading this.

As everyone knows, the bar for amending the Constitution is very, very high—two-thirds of both houses of Congress, three-quarters of state legislatures. It can also be done by a convention at the instigation of two-thirds of legislatures, but that's never happened, and it's still a high bar to clear.

The problem is that, at any given time, a sizable chunk of the population, and thus a sizable chunk of the members of Congress and of the state legislatures, believes that the system works to their benefit. As a general rule, the Electoral College gives disproportionate power to swing states, to lightly populated states, and to states controlled by the minority party. So, there will always be 15 to 25 states that say "We like things just as they are, thank you very much." If the Democrats were to steal a couple of elections thanks to the Electoral College, that would still be true, it's just that the list of 15 to 25 states would be different.

Maybe one of the workarounds, like the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, will eventually be implemented. But even that is very slow going, and runs into some of the same obstacles as a constitutional amendment (not to mention the numerous legal challenges that would be triggered should the NPVIC come into effect). At the moment, the NPVIC has been adopted by just 16 states.

C.J. in Lowell, MA, asks: In response to a question from R.C. in Des Moines regarding continuity of government you concluded with a reference to "extraordinary, but ill-defined, war powers granted by the Constitution." Where are you getting this? I just re-read Article II to refresh my memory and all it grants to the president is the power to be commander-in-chief specifically to the armies and navies of the United States as well as the state militias when federalized. It in no way seems to broaden his civilian authority. Even the suspension of habeas corpus is mentioned in Article I, which to me implies Congressional rather than Presidential prerogative. I also see no authority to declare martial law and I'm pretty sure states set election timetables.

(V) & (Z) answer: When the Founders wrote the Constitution, they reasoned that if the U.S. was to undertake an offensive war, then there should be discussion and broad consensus, which is why Congress is given the power to formally declare war.

However, they also took the view that in a circumstance where the U.S. has to fight defensively, then the president, as commander-in-chief, implicitly acquires extraordinary powers that he would not normally have in order to mount that defense. There is a fair bit of logic to this; if the Canadians show up on a Friday night in December and start dropping maple syrup bombs from Chinese-made balloons, the country really can't wait until Congress reconvenes, debates, and passes some sort of resolution. Time is of the essence, and that was particularly true back in 1787, when some members of Congress needed a month or more to travel to the capital city.

This interpretation of things is borne out in the notes that some attendees to the Constitutional Convention (e.g., James Madison) made of the discussions that took place there. The notion is also present in the Federalist Papers, and has been sustained by the Supreme Court, most notably in the Civil War-era Prize Cases. In SCOTUS' rulling, Justice Robert Cooper Grier, writing for the majority, asserted: "If a war be made by invasion of a foreign nation, the President is not only authorized but bound to resist force by force. He does not initiate the war, but is bound to accept the challenge without waiting for any special legislative authority. And whether the hostile party be a foreign invader, or States organized in rebellion, it is none the less a war."

Were the U.S. to be attacked in a manner that wiped out some huge percentage of the government, then that would clearly be a defensive situation. And we guarantee that the president, or the person who succeeded to the presidency, would stretch the office's war powers to their very limit. And they would get away with it (note, for example, all the stuff Americans went along with after 9/11).

T.R. in Vancouver, BC, asks: You've mentioned many times, including in your comments on Sen. Dianne Feinstein's (D-CA) retirement, that for her aspiring senators, youth is an advantage because it takes a long time to accrue seniority (and, hence, power) in the Senate. Is this supposed to be a bug or a feature? It seems undemocratic—why should a state have less of a say just because its senators haven't been around as long?—as well as giving incumbents an unfair advantage in reelection races, since they can say "Vote for me until you want to wait 20 years for my opponent to be in a position to get anything done."

(V) & (Z) answer: There are two paths to power in the Senate. The first is to rise up the ranks of leadership, and to serve as whip, minority leader, majority leader, etc. This usually takes time, but not always. Bill Frist (R-TN) managed to become majority leader in just 8 years.

The second path to power is to rise up the committee ranks to become chair of an important committee, like the Senate Finance Committee or the Senate Judiciary Committee. On committees, the leadership positions are based on length of service in the Senate in part, but mostly on length of service on that particular committee. Undoubtedly, part of the dynamic here is that two-decade senators don't want to be leapfrogged by some Johnny-come-lately. But the primary reason it's done that way is that running a committee takes a lot of experience and specialized expertise. And there's no shortcut, you have to put in the work.

In the end, "fair or unfair" is kinda beside the point. The system is set up the way it is because it has to be set up that way. Further, there are 50 states and only a dozen or so prominent positions, so at any particular time, the majority of states are getting the short end of the stick.

C.P. in Silver Spring, MD, asks: With the news over Reps. Adam Schiff, Eric Swalwell (both D-CA), and Ilhan Omar (DFL-MN) getting removed from their committees I wanted to ask, what exactly are the differences between a standing and select Committee in the U.S. House? Have both types been around since the first Congress? Can one be converted to the other?

(V) & (Z) answer: No, Congress has not always had both types of committees. Early on, there were only select committees, which were created to perform some particular task and then were disbanded. The House did not have standing committees until the Third Congress (and then, it was only a few of them) while the Senate didn't have them until the 20th Congress (and, once again, it was only a few). Eventually, standing committees became much more common, and were used to shoulder more and more of the daily job of legislating, while select committees became less common.

Generally speaking, consistent with the notion that they are doing part of the heavy lifting of running the country, standing committees are established by the rules of the chamber, their membership is submitted to the entire chamber for approval, and they are empowered to refer legislation to the floor for a vote.

Since select committees are ostensibly task-based, they are established by resolution, their membership is usually controlled by the speaker/majority leader, and their powers vary (but do not generally include the power to refer legislation to the floor for a vote). Some select committees have evolved into de facto standing committees, like the House Select Committee on Intelligence. And while these select committees could be converted into standing committees, they generally aren't due to inertia and the fact that speakers/majority leaders like having a little extra power over them.

E.W. in Skaneateles, NY, asks: Why is the threshold above which salaries and wages are not subject to FICA deductions ("the cap") set to $160,200? Is that indexed for inflation or was it the original value? Why have any cap at all?

(V) & (Z) answer: The FICA cap was originally $3,000. It is recalculated by the Social Security Administration each year, not based on inflation (at least not directly), but instead on what is known as the National Average Wage Index. (NAWI). If the NAWI goes up, say, 5.5% in 2023, then the FICA cap will go up 5.5% for 2024.

There are at least a couple of arguments for the cap. The first is that benefits are also capped (the current maximum is $4,555/month), so it is only fair to cap the tax. Even with the tax cap, higher-earning Americans will get less of their money back from Social Security, on average, than lower-earning Americans will. The second argument is that if the cap is raised too high, it will cause employers to shift compensation to things not subject to the FICA taxes (like, say, 401k payments), and so the government would still lose out on that money.

Note that we are not endorsing these arguments, just passing them along.

P.N. Oakland, CA, asks: I'd be interested in an opinion on the teaching of history, which we all know is also a political question. A friend of mine was "appalled" at his child's World War II unit at a local public high school, which included "1 week on the causes of the war, 3 weeks on the Japanese internment camps, and 1 day each on women in World War II, the Holocaust, and LGBTQ issues during the war."

On one hand, I can see that no 9th grade history unit is going to manage a comprehensive treatment of World War II and there can be real educational merit in emphasizing subjects that are currently relevant (treatment of marginalized people) or locally relevant (certainly, Japanese families from Oakland and the Bay Area were sent to camps).

On the other hand, I wonder why we (the libs) make it so easy for people like Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) to score political points by taking things to an extreme, where reasonable people (i.e., not DeSantis, but maybe some of his voters) can see political distortion in the curriculum.

Is what makes an acceptable curriculum purely in the eye of the beholder these days, or are there reasonably clear professional standards to be applied? Assuming the latter, where does the above curriculum land? I'd be interested in both your opinions as two educators and one historian.(V) & (Z) answer: (Z) is actually in a far better position to answer this, so this is primarily his perspective.

It's hard to speak with total confidence without actually seeing the curriculum, of course. That said, it's possible to make some pretty decent guesses. To start with, the topics you list are all homefront topics. That is to say, they are all related to the civilian experience of the war. A person might well say "Where is Midway? Where is D-Day? Where is the Battle of the Bulge? Where is Douglas MacArthur? Where is George Patton?" But those are all warfront topics. And warfront topics are really tough, because you can't explain the material in one or two class sessions. Either you go all-in and you do it properly, or you don't do it at all. On top of that, a lot of history teachers (and, for that matter, history professors) don't really have the expertise to do it properly. Making sense of all the things going on, in all the theaters of the war, and trying to pull them together into a cohesive narrative is exceedingly challenging.

Meanwhile, without seeing specifics, it's hard to know how much overlap there is between topics. For example, doing just one day on the Holocaust might seem light. However, the week on the causes of the war must include some significant discussion of antisemitism, the rise of Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, etc., right? And so, the day on the Holocaust is really more like "Holocaust, Part II," since Part I would have been covered in the week on causes.

And then there's the thing that stands out like a sore thumb, namely the 3 weeks devoted to Japanese internment. (Z)'s strong suspicion is that the internment unit includes some substantive activity that is meant to give depth to the overall World War II unit. For example, there are several very good, and very age-apropos books on internment, like Farewell to Manzanar and No-No Boy. Maybe the students read one of those, and then there is a significant discussion or essay component. There might also be some sort of primary document analysis; we have lots and lots of pictures and letters from internees. Or, this might be the portion of the unit that includes some sort of field trip. American students can't exactly visit a 1943 Boeing plant, or tour Dachau, but Manzanar and Tule Lake are both still there, and are within range of most California schools.

In the end, because people were once students themselves, and because they feel they are supervising their children's education, they feel entitled to weigh in on school curricula. Politicians like DeSantis take advantage of this dynamic, making political hay out of curricular decisions that are: (1) often quite justifiable, and (2) deliberately taken out of context.

The fact is that many (perhaps most) parents don't know all that much about being an educator. Quite often, they also don't know much about the specific subject matter. They would not presume to tell their doctor, or their lawyer, or even their mechanic "Hey! I know better than you!" But they feel free to say that to teachers all day long.

F.S. in Cologne, Germany, asks: Some UFO-related questions: What happened in Roswell, New Mexico, in 1947? What is the truth about Area 51? And is it true that many people were in full panic mode after hearing "The War of the Worlds" in 1938 (narrated by Orson Welles) although the audience was told in the beginning that "The War of the Worlds" is purely fictional?

(V) & (Z) answer: Roswell and Area 51 are both artifacts of the Cold War. That is to say, the government was being very secretive about its projects, and the places where it conducted tests and experiments, because they didn't want the Russians (and other enemies) to know what was going on. Meanwhile, many civilians were experiencing a high level of fear in the 1940s and 1950s. A common cognitive phenomenon when coping with mysteries and with fear is to fill in the blanks with fanciful explanations that make the listener feel better about things. Anyhow, both places are exactly what they claim to be: Top Secret military test sites. Nothing more.

As to the panicked reaction to "The War of the Worlds," it's such a great story that you can see why it's lingered for close to a century. But it's also largely nonsense. That story was propagated by newspaper reporters, who were interested in discrediting the new (and competing-with-newspapers) medium of radio. There was also a substantial racist component; nearly every story reported that the alleged panic was centered in Harlem (in other words, Black people).

Welles, for his part, played along with the story for the rest of his life. Not because he hated radio or Black people, but because it burnished his (otherwise well deserved) reputation as an artistic genius.

C.R. in St. Louis, MO, asks: You referred to our past two presidents as receiving gentlemen's Cs in college. This was an allusion to their less-than-stellar scholarly studies, I suppose. In the past, a gentleman's C was not really for lack of intelligence; it just wasn't seemly for a gentleman to try that hard for a better grade. See this page from Franklin D. Roosevelt's Harvard foundation for his grades and a conversation about the gentleman's C.

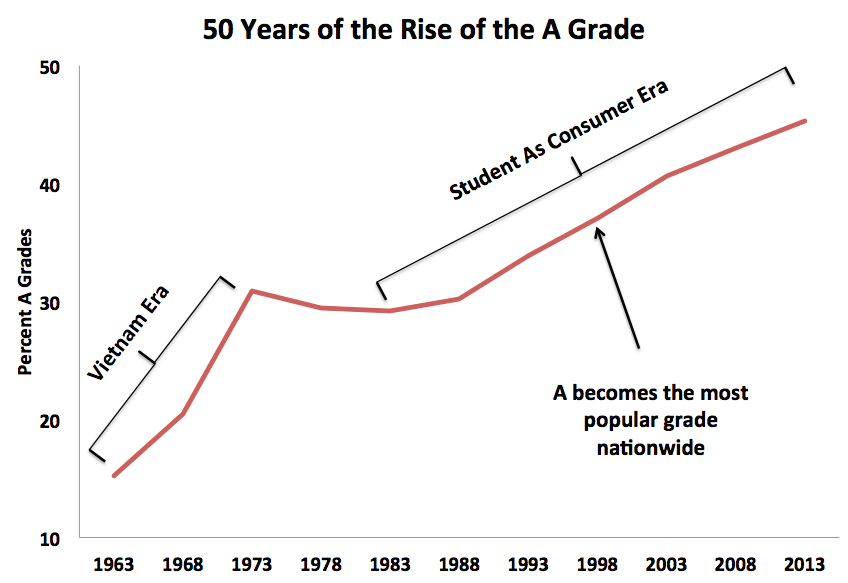

Now, my question: Was the Vietnam draft exemption for a B or better average a cause for grade inflation and a change in the gentleman's C meaning?(V) & (Z) answer: There is no question about it; the evidence is clear. Stuart Rojstaczer and Christopher Healy, of Duke and Furman Universities, respectively, have studied grade trendlines over the years, and have put their findings online at gradeinflation.com. Here, for example, is their chart of the percentage of students receiving A's between 1963 and 2013:

Their other charts and figures show the same thing, in a variety of ways.

A.J. in Ames, IA, asks: After reading the list of U.S. senators with the largest vote totals, who are the longest-serving senators with the fewest votes? (I'm assuming Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-IA, might be near the top of that list—career politicians from small population states.)

(V) & (Z) answer: This is a little difficult to answer, because what is "worse"? A three-term senator who only collected 500,000 votes in their career? Or an eight-term senator who only collected 1,000,000? So, we are going to give you three pieces of information.

First, the lowest vote total we could find for any senator who won election is 11,550. That was for Republican Tasker Oddie, who triumphed in a three-way race in Nevada in 1920. However, he won reelection, and also got votes in two losing campaigns, so his lifetime total is in the 80,000 range.

Second, the lowest lifetime total we could find is 25,434 for Josiah O. Wolcott, a Democrat sent to the Senate by the people of Delaware for a single term in 1916. These low totals both come from the same 10-year period because that was, of course, the first decade in which senators were elected by a direct vote. And in that time, Nevada was the least populous U.S. state while Delaware was only two spots higher.

Finally, the longest-serving senator in U.S. history is Robert Byrd, of the low-population state of West Virginia. Here are his vote totals for his various election wins:

Year Votes 1958 381,745 1964 515,015 1970 345,965 1976 566,359 1982 387,170 1988 410,983 1994 290,495 2000 469,215 2006 291,058 Total 3,658,005

In other words, in his record nine U.S. Senate victories combined, Byrd got about 40% fewer votes than Dianne Feinstein got in just her most recent victory (5,976,440).

J.H. in Boston, MA, asks: You told S.G. in Fairfax that you wouldn't change the name of the site if the Electoral College were removed from the American political system. That had me wondering about FiveThirtyEight. Would they change the name if a new state were admitted and the number of electoral votes went up? Or was changed for any other reason? Surely this question is for Nate Silver (is he still in charge?), not you guys. But maybe they've addressed it at some point and you happen to know.

(V) & (Z) answer: He has addressed it, and we do know. Back when he thought statehood for Washington, D.C., was imminent he wrote a brief essay explaining that the name would stay the same even if the number of EVs changed.

J.K. in Freehold, NJ, asks: Question for (Z): Would you happen to know if the faulty charging station you encountered was a Blink product? My son, with his wife and 5 wonderful young kids, recently moved from New Jersey to Arizona to take a job with Blink, so I have an interest in Blink's future and need to know if a warning to him is in order at this point.

(V) & (Z) answer: No. (Z) has generally had good luck with Blink, and with ChargePoint, and with Flo, and with Electrify America and with EVCS. On the other hand, you should tell your son not to take a job with EVGo, because those break all the time, and it was one of their chargers that caused problems on the aforementioned Thursday night.

In other news, EVGo is one of the relatively few networks that imposes a fee for initiating a charge ($3), regardless of how much electricity you actually use. Probably just a coincidence that it's the network where the charge is most likely to fail 3 minutes in, forcing the user to start over and pay another fee.

We're going to do some juggling here. We haven't yet run the podcast suggestions, so we're going to do that now. That was actually the question two weeks ago. And in response to the question from last week, we got a lot of interesting potential presidential matchups. So, we're going to kick those to the regular week, so we can do a couple days' worth. Anyhow, as a reminder, here is the two-week-old question that these readers were responding to:

J.B. in Seattle, WA, asks: I'm listening to the Bulwark podcast on Tuesday with two educators discussing the state of education and censorship. Got me thinking: Is there a format we may ever hear you both speak? Either on another podcast or even a periodic one of your own? I'm sure my $5/month contribution is going to seal the deal on this! Thanks for all you do guys!

And here some of the answers we got in response:

F.S. in Cologne, Germany: I would only be interested in a podcast by (V) and (Z) if it is about issues which (V) and (Z) disagree on (at least partly). A podcast wouldn't be so interesting if you talk about issues which you entirely agree on. A very interesting podcast would be if (Z) and a Canadian graduate of USC who is a fan of the Chicago Bears are the participants.

C.D. in Guernsey, Channel Islands: Having moved from North America to Europe, I have noticed that politics on the continent is very poorly understood in the U.S. This is (I think) mainly due to a language barrier, but even where that is not an issue, media coverage of Europe in the U.S. seems sparse and superficial.

While there is a higher basic knowledge of U.S. politics in Europe than vice-versa, I believe that much subtlety is missed. It's difficult for continental Europeans to understand the motives of American politicians, the attitudes of American voters to issues, the federal division of powers and the role of media in shaping attitudes.

Since one of you is based in the Netherlands and the other in the U.S., have you considered a podcast comparing the politics of the U.S. vs. Europe? Europeans might be very interested in topics such as "Why do so many Americans shrug their shoulders at seemingly obvious problems like gun violence/homelessness/overcrowded prisons/healthcare debt? Why is there such American media apathy about Europe despite the huge investment of America in its affairs during the Cold War?" while Americans might want to hear a podcast that digs into things like: "What does the European Union even do? Why do some European countries have a consensus on issues that tear Americans apart?"

P.L. in Los Angeles, CA: Books about history and the arguments they make/new perspectives they offer.

G.Z. in Walnut Creek, CA: A "This date in U.S. history" podcast. Or this week. Each episode would pick a year and date. You could just focus on 1900's or all of U.S. history. For all of U.S., you'd have almost 245 years of days to pick for any episode. In theory, the podcast could last 245 years! Well, actually, by the year 2268 you'd have another 200 years of days... so, I guess if could go on forever?

A.I. in Honolulu, HI: A live Q&A or discussion with readers. Some of your readers could be interesting interview subjects, too.

J.B. in Arlington, MA: An episode from history that can teach us something about a current problem or issue. The format could be a panel—adding one expert on the historical event and one on the current issue.

K.H. in Albuquerque, NM: A weekly or monthly deep dive into the nerd-world of poll wonkness would be fascinating.

J.W. in Newton, MA: I suggest a series at the intersection of technology and history. Each episode could focus on how a particular scientific or technological innovation played an oversized role in world history. Obvious examples from warfare would include the rifle, the machine gun, the cannon and its descendants, the longbow, communications and encoding technologies, the calvary, game theory, and nuclear weaponry. But it would be great to focus on other tech contributions to human history like plumbing, economics, specific agricultural technologies, mass production, navigational technologies, skyscrapers. The list is endless. You could consider bringing in guests that may specialize in a form of tech around which an episode revolves.

B.J. in Arlington, MA: Don't go for the big names, those are covered already. You guys are great at small details. So interviews with some of the less/non-visible people you write about in government, academia, state political organizers, the staff mathematician, etc.

D.M. in Santa Rosa, CA: I would love to hear a podcast that gives the E-V.com treatment to the politics of the Civil War period and Reconstruction. Follow the political battles and politicians of the lead-up, the war, the 1864 election, victory and then maybe through Grant's presidency as Reconstruction is dismantled. Get the transcontinental railroad in there too. Do it like a time lapse such that each week in the present you cover a month in the past, or whatever it takes to finish in 12 to 18 months. Focus on the politics not the battles.

S.R. in Stockton, CA: I avoid podcasts at all costs but if the wonder dachshunds were co-stars, I'd probably make an exception.

Some excellent suggestions! We have many more things we want to do with the site before even considering something like this, but this at least gives us food for thought.

Here is the question for next week, which dovetails pretty nicely with the podcast question:

L.J. in Los Angeles, CA, asks: If there was an app or a site that read E-V.com to us, which performer would be best to read it and why?

Submit your answers here!