Previous | Next

New polls:

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Happy New Year!

Welcome to 2022. Let's hope it is better than 2021. For political junkies, it should be exciting, since it is an election year. And there are at least half a dozen interesting Senate races and another half dozen gubernatorial races, plus a handful of House races that will get a lot of attention. Please come along for the ride.

Saturday Q&A

A good mix this week, which makes sense given the lack of news.

Current Events

R.S. in Huntington Beach, CA, asks: As the number of Americans becoming infected, hospitalized, and dying from COVID continues apace, a somewhat morbid question comes to mind: As the number of people impacted skews disproportionately to the right side of the political spectrum, will this reality impact the presidential election? Will the disproportionate number of COVID deaths among the ranks of Republicans be substantial enough to change what otherwise would have been a Republican victory into a Democratic victory in any particular state? I understand that in significantly red states this would not be the case, but there seems to me to be enough purple states that have razor thin margins (e.g., Florida) that a disproportionate impact changing what would otherwise have been a victory for the red team into a victory for the blue team is possible. Any thoughts from the resident statistician would be greatly appreciated.

V & Z answer: We get this question, or a variant of it, every week. And the answer is that while it is possible that the COVID dead being disproportionately Republican could affect a statewide or national election, it's not probable.

The damage wrought by the pandemic is going to be greatest in places where people are particularly likely to be careless (e.g., not wearing masks) or particularly likely to be unvaccinated. Since Republicans are now considerably more likely than Democrats to be careless, and considerably more likely than Democrats to be unvaccinated then, by transitive property, it means that the pandemic damage is going to be greatest in places with a large number of Republicans. Or, to put it another way, the reddest portions of the map. However, those are also the exact portions of the map where the loss of a few hundred (or a few thousand) Republican votes is least likely to matter.

That said, the most likely scenario by which COVID-related Republican deaths flip the presidential election is if the EV tally is close, and a few thousand (or a few hundred) votes in Florida are enough to give that state to the Democrats. That state is purple, has a lot of EVs, and has not done well in terms of its COVID management.

J.L. in Los Angeles, CA, asks: Where is Ron DeSantis? Don't worry if you can't answer. Neither can his staff.

V & Z answer: The Gambler advised that you gotta know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em, know when to walk away, and know when to run.

Similarly, it's not surprising that a politician who has savant-level instincts when it comes to sniffing out opportunities to insert himself into the national conversation is also quite capable of vanishing when circumstances call for it. For example, when COVID runs roughshod over his state, at least in part due to policies and behaviors he promoted.

K.W. in Thousand Oaks, CA, asks: What do you think is behind Donald Trump publicly coming out in support of the COVID vaccine, seemingly to his own detriment in regards to his supporters? I'd like to think he's just seen the light, but everything Trump does is about the grift. How does this benefit him?

V & Z answer: To start, we are going to correct you. Everything Trump does is about Trump; grift is just one possible form of benefit.

In any event, there are three possible explanations we can think of, and they could all be correct. The first is that he's figured out that if he runs again, as someone whose only hope is a narrow win, losing hundreds of thousands of Republican voters is not helpful. The second is that he doesn't like the thought of being personally responsible for people dying. The third is that he's trying to rewrite the history of the pandemic to make himself the conquering hero, and he can only do that if he get's the lion's share of the credit for the vaccine and people actually use the vaccine.

C.S. in Madison, WI, asks: It has been noted many times on this site that CRT isn't taught in K-12. However, people at the school board meetings believe that CRT is being taught. What is their definition of CRT?

V & Z answer: Narrowly, to them CRT means "anything about race and racism in America, in particular anything that suggests that white people had or have built-in advantages." Broadly, to them CRT means "anything we don't like being taught," with CRT therefore just serving as an excuse for parents and other activists to insinuate themselves into curricular decisions.

P.L. in Denver, CO, asks: What would happen if the January 6 Commission and/or President Biden decided to release the various records that Trump has been fighting to keep private? What, if any, penalty would the commission or President suffer?

V & Z answer: Keep in mind that the January 6 Commission does not have the documents, and that the court case is about whether or not they can get them. So, Chair Bennie Thompson (D-MS) & Co. don't have the ability to release them right now. If the Commission somehow acquired the documents without approval and then released them, they could be in serious trouble. That would be a violation of 18 U.S. Code 798, since those documents are currently classified. It might also be deemed theft of government property.

On the other hand, if Joe Biden were to release them to the 1/6 Committee, or even to the general public, he would be in the clear. First of all, the president has unlimited authority to classify or declassify information as they see fit. Second, as Donald Trump helpfully demonstrated, sitting presidents are (apparently) immune from prosecution. So, even if AG Merrick Garland found a statute and alleged that Biden was in violation, that would be academic. Congress could, of course, decide that releasing the documents was an impeachable offense and could impeach Biden, convict him, and remove him from office. But do you think that's at all possible? We don't.

So why hasn't Biden just released the documents, then? Part of it is philosophical; he wants to respect the process and the balance of powers and he wants to show that, in contrast to Trump, he does not believe that a president should do whatever he wants just because he technically can. And part of it is political; he doesn't want the bad optics that would be involved in disregarding the Supreme Court like this, especially since it would give House Republicans something to "investigate" endlessly if they regain control of the lower chamber.

G.B. in Santa Ynez, CA, asks: Why hasn't Joe Biden issued an executive order prosecuting anyone who threatens election officials? How can this be protected speech?

V & Z answer: To start, there are most certainly heavy-duty First Amendment issues here. The courts have made clear that for the government to take any action, a threat must be real and it must be imminent. Consider these three declarations:

- "I would like to see all of my local poll workers killed."

- "I am going to nuke my neighbor Joe tomorrow, because he's a Democrat and a poll worker."

- "I am going to shoot my neighbor Joe tomorrow, because he's a Democrat and a poll worker."

Threat #1 is not imminent, and threat #2 is not real, since the average person does not have a nuclear arsenal at their command. Threat #3 would be actionable, and would likely prompt some action if the person making the threat were foolish enough to state it publicly.

The reason Biden has issued no executive order is that there is no value in doing so. An executive order cannot create new laws by fiat, it can only instruct executive branch employees how the president wants current law implemented. So, there is nothing Biden can do about threats #1 and #2, and the DoJ is already prepared to address threat #3 without needing his input.

Politics

M.B. in Pittsboro, NC, asks: As the anniversary of January 6th approaches, I am dreading it, not so much in fear of another frontal attack on the Capitol in Washington, DC, but worried about more local efforts to disrupt state capitals...à la Michigan. I know there are plenty of agencies that are monitoring suspected groups, and hopefully they are on top of things. Have you heard any rumors of disruptions planned in state capitols?

V & Z answer: We have not seen anything, and we doubt there will be much activity—if any.

The first issue is that storming a state capitol on Jan. 6, 2022, is not—for lack of a better term—sexy. The folks who rioted on 1/6 were at one of the most famous buildings in the world, and they thought they could save their beloved leader, or at very least lash out against those who would banish him. By contrast, the capitol buildings in, say, Wisconsin or Alabama or Nevada are not internationally famous, and there would be no clear benefit to accosting them.

The second issue is that there are only so many fanatics out there. Nobody really knows how many people were present for the events of 1/6, but 25,000 is probably a pretty good ballpark figure (some estimates place it as low as 10,000, others as high as 40,000 to 50,000). Anyhow, 25,000 people makes for a pretty dramatic scene, and for some very concerning photo ops, and very possibly for the outbreak of some level of violence. Divide 25,000 (or even 50,000) 50 ways, and you're talking fewer than 1,000 people (and maybe fewer than 500). That's a very different dynamic.

And the third issue is that while it's pretty easy to get to Washington from most of the country, a lot of state capitols aren't all that accessible. A lot of them are situated in locations that made sense in the 19th century, but are kind of off the beaten path today. There are nine capitals, in fact, that do not have commercial passenger flights (Annapolis, Carson City, Concord, Frankfort, Jefferson City, Little Rock, Montgomery, Santa Fe and Springfield). There are also five capitals that are not on an interstate highway (Carson City, Dover, Jefferson City, Juneau and Pierre). It may very well be easier to get 1,000 Missourians together in Washington than to get them together in Jefferson City.

M.B. in Cleveland, OH, asks: I have seen the observation that several Supreme Court justices became more liberal throughout their time on the court (Harry Blackmum, Sandra Day O'Connor, Anthony Kennedy, David Souter, maybe John Roberts). I haven't seen a discussion of justices becoming more conservative after being appointed. Have there been (recent) justices who drifted notably rightward? Is there anybody currently on the Court whom you would see as a potential drifter, one way or the other?

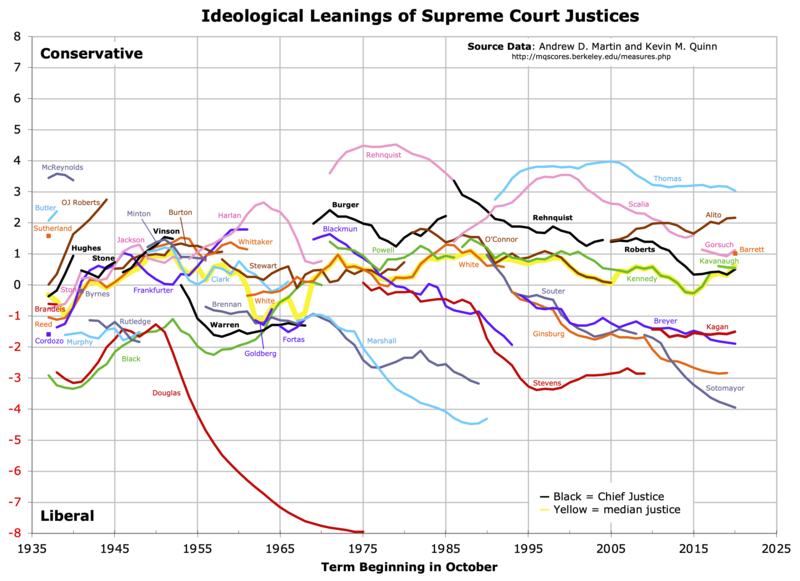

V & Z answer: Our current understanding of what makes someone "liberal" versus what makes someone "conservative" dates back to the New Deal era, so studies of Supreme Court justices' politics tend to start with the 1930s. And there have been a lot of those studies, which use various advanced statistical methods to try to put this on an objective basis. The most recent major study was conducted by political scientists Andrew D. Martin and Kevin M. Quinn, and this is the chart they produced, where the bottom half is "liberal" and the top half is "conservative":

As you can see, it's been a long time since a justice veered sharply in a conservative direction without eventually moving back to the center. Owen J. Roberts, way over on the left side of the chart, did it in the 1930s. And so did Hugo Black, who went from pretty lefty to basically centrist. But others who shifted to the right, like John Marshall Harlan II or even Antonin Scalia, eventually shifted back to a more moderate position.

The great majority justices stay fairly consistent, like Clarence Thomas has, or else veer leftward—sometimes sharply so. For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt certainly got his money's worth out of William Douglas. Not only did Douglas have the longest tenure in Supreme Court history (36 years), but he also ended up as the most liberal justice of the last century (and probably ever). Harry Blackmun shifted pretty far left, as did John Paul Stevens. Further, some of the famous leftists, like Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, went from "moderately lefty" to "really lefty."

As to possible drifters on the Court right now, Chief Justice John Roberts is the obvious answer. He's already drifted some, as shown in the chart, and he's also worried about the "balls and strikes" reputation of the Court, a concern that is pulling him toward the center. Samuel Alito is heading further right, if only slightly, and Thomas has consistently been one of most right-wing justices in the Court's history. Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett don't have enough service under their belts for there to be meaningful trends in their jurisprudence, but we see nothing about their backgrounds or their votes so far that suggest they are anything but reliable conservatives.

A.K. in Boyle Heights, CA, asks: What are odds, do you think, of a Congress passing a bill restricting the Supreme Court's jurisdiction?

V & Z answer: Fairly low. There is probably less than a 50% chance that the Democratic votes exist for such a bill. Then, there is surely less than a 50% chance that the votes needed to change the filibuster, which would have to happen because 10 Republicans would never support this, exist in the Senate. When you have two sub-50% events, and those events are not really correlated, the odds of both of them happening are not good. If you assume there's a 40% chance the votes are there for the bill, and a 15% chance the votes are there for a filibuster change, then that means there's just a 6% chance of both things happening.

The calculus will change if Roe is struck down, but until such time, we don't see it happening.

B.S.M. in Split, Croatia, asks: When was the last time the U.S. Supreme Court was made up of a majority of Democratic appointees?

V & Z answer: May 14, 1969. On that day, the Court had two Franklin D. Roosevelt appointees (Felix Frankfurter and the aforementioned William Douglas), one John F. Kennedy appointee (Byron White), and two Lyndon B. Johnson appointees (Abe Fortas and the aforementioned Thurgood Marshall) as compared to four Dwight D. Eisenhower appointees (Earl Warren, Potter Stewart, William J. Brennan, and the aforementioned John Marshall Harlan II). Then, Fortas resigned, to be replaced by Richard Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun on May 14, 1970.

It is worth noting that Warren, while a Republican appointee, turned out to be a liberal (see the chart in the above answer). That means that even after Fortas left, there were five liberals as compared to three conservatives. However, Warren retired on June 23, 1969, the day that Nixon appointee Warren E. Burger received his commission as Warren's replacement. That made it four conservatives to four liberals in mid-1969, and then five conservatives to four liberals once Blackmun was seated in 1970.

Not that shifting the Court's balance did Nixon a fat lot of good. Burger wrote the unanimous opinion that said that Nixon had to hand over the Watergate tapes.

E.W. in Silver Spring, MD, asks: In your item "Judge not, Lest Ye be Judged," you wrote that longer control of the presidency by Democrats provides a hedge in regards to the Supreme Court. Could you explain how?

V & Z answer: We didn't mean that as a general principle, necessarily, just a description of the current state of affairs.

The Supreme Court, of course, is currently dominated by Republican appointees. However, the Supreme Court also hears less than 200 cases per year, and often closer to 100.

By contrast, the rest of the federal court system hears about 400,000 cases per year. And the non-SCOTUS federal judges are about 52% Democratic appointees right now, with the number headed to about 55% in the near future. So, even if Democratic appointees are not deciding the "glamour" cases, they are deciding a disproportionate percentage of the overall federal caseload.

A.L. in Osaka, Japan, asks: E-V.com has given a lot of space to the possible fall of democracy in America. I was talking to my dad about this, and he said most Americans wouldn't really mind as long as the economy was buzzing along. Most people understand politics through the cultural wars and an authoritarian regime would reflect their political philosophy.

V & Z answer: We would say there are a couple of faulty assumptions here. People may take their democratic rights for granted, but if someone tries to take them away, there will be a huge backlash. Further, the "culture wars" people might suck up a disproportionate amount of oxygen, but we don't think that they represent a majority.

I.K., Queens, NY, asks: Many of the tributes I saw for Harry Reid mentioned he was a kingmaker. In 2019, articles were running about which Democrats were kissing the ring, and who Reid seemed likely to endorse (Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-MA, seemed to be a popular guess). His endorsement of Joe Biden before Super Tuesday was an important salvo in the consolidation of moderates to stop Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT, and if some rumors are to be believed, he personally talked with Sen. Amy Klobuchar (DFL-MN) and convinced her to drop out.

With Harry Reid gone, who do you think is going to be the next Democratic kingmaker? (I'd also be interested to hear from other readers on this!) The role is Barack Obama's for the taking, but he's far too prudent and diplomatic to take it. The Clintons are too unpopular. Al Gore is busy saving the environment. Jimmy Carter's too old. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and especially Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) would be viable options, if they weren't busy trying to run Congress (and also appear diplomatic in doing so). Who does that leave?V & Z answer: Well, don't overlook Pelosi and Schumer so quickly. They might not do their maneuvering in the open, since that would be impolitic, but they certainly do have huge influence over potential candidacies. And Pelosi is getting close to retirement, and so will soon be an above-the-fray party elder like Reid was.

Beyond that, Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-SC) is an obvious answer, since he's perceived as a spokesperson for Black Democratic voters. Particularly Black Southern Democrats. Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) has kingmaker potential, if he can get reelected, for the same reason.

There's also Donald Trump. If he attacks a Democratic candidate or officeholder, that person's approval rating among Democrats goes up 5-10 points. Call it the "Schiff effect."

We are happy to run some thoughts from readers, if they have them.

D.D. in Hollywood, FL, asks: I know this is past it's sell-by date but I've always wondered why was it that President Obama never revealed his college grades. I'm assuming that they would be better than average and the disclosure wouldn't have hurt his electoral chances, so it must be something else. I figure this is right up both of yours expertise, or at least I hope it is.

V & Z answer: Some readers might find this video to be of interest (though it's 27 minutes, so maybe not the whole thing). It's Jon Stewart appearing on Bill O'Reilly's show on Fox in 2011. And the Obama outrage du jour was that the rapper Common was invited to participate in an event at the White House, and Common once spoke out in defense of a convicted cop killer (who Common believes to be innocent).

Stewart spends virtually the entire interview pointing out examples of white musicians who have written songs or otherwise defended convicted felons (including convicted cop killers), including Bono/U2, Bruce Springsteen, and Bob Dylan. And O'Reilly twists himself into knots trying to explain how those situations are different from the Common situation, and how the Common situation is highly significant, and how George W. Bush was entirely within his rights to invite Bono to the White House, etc. In the end, it is clear that the real difference is that Common is Black and a rapper, and Obama is Black and a Democrat, and that is the fuel that keeps the outrage machine running.

Obama did not release his grades because there was nothing but downside for him in doing so. Whether one likes him or not, it is abundantly clear that he is an educated, intelligent, well-spoken man (as it was clear with Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, Richard Nixon, and John F. Kennedy). He did not need to release his grades to prove that.

Meanwhile, no matter what Obama's grades were, the spin machine would have found a way to turn them into a negative and an obsession. If he got straight As, then he would have been attacked for being arrogant, and an egghead, and a pointy-headed intellectual. If he got a low grade in one class, then that would have been turned into the new Watergate. "He got a C+ in U.S. History? Do you need any more proof that he hates America?" Or maybe "Wow, decisions about a $2 trillion budget are being made by a guy who got a B- in accounting." And if Obama's early-career grades from Pepperdine were weaker, and his later-career grades from Columbia and Harvard were stronger, it wouldn't be taken as an indication of a young student who pulled his sh** together, as young students often do. No, it would be held out as ironclad proof that he was a creation of Affirmative Action.

In addition, Obama was (rightly) sensitive about double standards based on race. He was not going to do something, as a Black president, that has never been demanded of white presidents.

Note that he refused to release his long-form birth certificate for a very long time for these very same reasons. Those who know he is an American don't need further proof. And those who insist he is not are always going to find excuses to believe in their conspiracies. Meanwhile, releasing the document—which finally he did because the "what is he hiding?" chatter got so loud—implicitly, and regrettably, suggested that a Black president has to "prove" his Americanness, even though no white president has ever had to do that.

Civics

M.U. in Seattle, WA, asks: Many things I've read over the years regarding Harry Reid in regards to being majority leader always made mention of his zealous use of a tactic called "filling the tree." Apparently, it's a way for the majority to obstruct the minority in the senate, and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) complained bitterly about it (imagine that!). I have read about the tactic but I don't really understand it. Can you help explain filling the tree, its history and use, and if McConnell as majority leader found it just as fun to use as Harry Reid did?

V & Z answer: Please understand that this gets very complicated based on the type of bill under consideration, as well as other parliamentary considerations. However, as a general rule, there are two different ways in which amendments are categorized. The first categorization is "perfecting" vs. "substituting." The former adjusts the text of a bill or amendment, while the latter replaces text wholesale. The second categorization is "first degree" vs. "second degree." The former amends a bill itself, the second amends an amendment. In theory, "third degree"—amending an amendment that itself amends an amendment—is possible, as are "fourth degree," "fifth degree," etc., but anything beyond "second degree" is not generally allowed.

Anyhow, if you have two different categorizations, and two different options within each, then it means you have a grand total of four possibilities, to wit: first degree perfecting, first degree substituting, second degree perfecting, second degree substituting. Those are the four amendment "trees." And, per Senate rules, each tree can only have so many "branches" (usually something like 4, 4, 2, and 1 for the four categories, which means a total of 11 amendments). Meanwhile, also by Senate rules, the Senate Majority Leader is first in line when it comes to submitting amendments. So, sometimes Reid would submit 11 meaningless amendments (e.g., "The word 'roof' on page 6 will be replaced by the word 'ceiling'"). That is "filling the tree," and would mean that Republicans could submit no amendments of their own.

Generally speaking, the Senate has tried to remain a calmer, more deliberative, more collegial body that makes sure the voice of the minority is respected. So, filling the tree was not terribly common before 2010 or so. Ultimately, the trick is only needed when two conditions are met: (1) the majority is trying to pass legislation, and (2) the minority is not interested in shaping the legislation as much as they are in inserting poison pills and performing other stunts. This is the situation Reid found himself in, and filling the tree was how he responded. McConnell's majorityship, by contrast, did not really meet the conditions. The Democrats are less inclined towards stunts and poison pills (which is not to say they are above them entirely). More importantly, the Republicans didn't really try to pass much legislation. They mostly spent their time confirming judges and arguing about the budget.

Thus far, Chuck Schumer has had little need of the tactic since the two major bills that were passed had some level of bipartisan support, which made it fairly easy to brush aside stunt amendments. When and if Build Back Better comes up for an actual vote, however, Schumer may have to dig into the Reid bag of tricks.

S.J. in Taipei, Republic of Taiwan, asks: According to Wikipedia, Kamala Harris has now surpassed Mike Pence in the number of ties she's broken with her casting vote as President of the Senate, ranking No. 5 overall.

My question is, what are the logistics of the tie-breaking vote? Do senators know in advance that a vote will end up tied (if so, how?) and have the Veep waiting in the Capitol? Or does the VP have a few hours/days to arrive at the Senate after the result of the vote is known and cast her tie-breaking vote?V & Z answer: Thanks to the existence and the skill of the whips (Sen. Dick Durbin, D-IL, and Sen. John Thune, R-SD, are the lead whips for their parties right now), whose job is to count votes, it's generally known well in advance when the VP's vote will be needed (or, at least, might very well be needed). And once the voting commences, a VP doesn't get any bonus time. Normally, the 100 members and the VP have 15 minutes to register their preference. So, the VP really needs to be in the building, or very close by, when a vote is imminent.

There is a somewhat famous story, which we've related before, of the occasion, in 1925, when Calvin Coolidge tapped Charles B. Warren to be AG. Warren was controversial, and the vote was sure to be close, and so VP Charles Dawes was in the Senate gallery in case his vote was needed. However, Dawes got bored with all the debating and, assured that there would be multiple hours before the vote was held, retired to his hotel for a nap. Of course, the debate ended more rapidly than expected, and the vote commenced more quickly than expected, and Dawes was forced to double-time it to Capitol Hill. He did make it in time, in the sense that the voting was still open when he got there. However, while the senators waited for him, one of them had time to reconsider their vote, with the result that there was no tie to break by the time he got there. It would have been 41 to 40 for approval if he'd just stayed in the Senate, but because he left, it ended up 41 to 39 against confirmation, and Warren was out of luck.

W.H. in San Jose, CA, asks: You wrote last week that you wondered which senators were going to present at the pro forma Senate sessions. I viewed two of them on C-SPAN and the only person visible on camera was Patrick Leahy (D-VT). Is there any way to find out what other senators (if any) were present? And why is Leahy running the sessions called by Mitch McConnell?

V & Z answer: The Senate posts reports on floor activity to its website, but they note that the page "does not include pro forma sessions where no legislative or executive action took place." So, watching the C-SPAN feed is about the only option. Luckily, there's rarely more than one senator present, and so seeing them when they take the dais tells the tale. During the break, it was Leahy twice (Dec. 20 and 23) and then Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) twice (Dec. 27 and 30).

So why did two Democrats end up with this duty, given that it's the minority that instigated the pro forma sessions? There is no public answer to this, but here are three possibilities:

- Protecting their turf: Yes, the dominant dynamic is Democratic vs. Republican, but there is also an executive vs. legislative tension. Chuck Schumer & Co. might be in support of the pro forma sessions, at least on some level, as a means of protecting the executive branch's power.

- Collegiality: The Senate is not as chummy as it once was, but these people are still colleagues and they still have use for votes from the other side of the aisle. Leahy was likely tapped because he was in town, he's pro tempore, and the sessions are held in his name and under his authority (when he's not there, they read a document in which he delegates authority). Meanwhile, Schatz is Jewish, and there are no Jews in the Republican conference. He may have stepped up because it's less problematic for him to be in town over Christmas than it would be for his Republican colleagues.

- Shenanigans: The Senate requires a quorum (51 people) to conduct business. However, by tradition and by rule, the existence of a quorum is assumed unless a member asks for a quorum call that proves otherwise. If the senator presiding over the pro forma session was willing to grossly violate the spirit of the rules, they could theoretically change the rules of the Senate unilaterally, since there would be nobody to ask for a quorum call. For example: "All points of order will henceforth require 60 votes to be carried." That would, in theory, make it impossible to change the filibuster, and would also make it impossible to change the rules back to what they were. It's doubtful that any member would try something like this, but it's also possible that Schumer's thinking is "better safe than sorry."

There are definitely occasions where the minority party handled all of the pro forma sessions during a break, so having the majority do it is not automatic.

History

C.D. in Chattanooga, TN, asks: You listed six (really seven, with 1960) disputed Presidential elections. Not counting 2020, since there's no way to fully know yet, how would you rank these in terms of lasting effects on the country?

Also, what do you feel was the least consequential Presidential election? Is it 1840, or did Harrison's near-immediate death have fallout?V & Z answer: Here's how we would rank them, from least to most:

- 1800: Jefferson was very likely to come out on top once the controversy was resolved, and if not, he would have been vice president and would have been elected in 1804. Meanwhile, the election led to the closing of a loophole in the Constitution, but that's about it.

- 1876: Yes, it ended Reconstruction, but Reconstruction was winding down anyhow, and had already ended in a number of Southern states. And Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel Tilden were not that different on policy, plus they lived in an era with a weak presidency. So, a Tilden win would not have changed much in terms of governance.

- 1824: This hastened the rise of the Democratic Party, and of two-party politics, and it also paved the way for Andrew Jackson to occupy the White House. However, all of those things were going to happen, sooner or later. Jackson, of course, would have been inaugurated in 1825 instead of 1829, and once he was in the White House, you can be damn sure he and Martin Van Buren would have whipped the Democratic Party into shape.

- 1960: As we've discussed in both the Q&A and the letters page before, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon were pretty different guys. And if they had swapped fates in 1960, it is possible that the Vietnam War goes very differently (or doesn't happen), that the Republican Party ends up as the civil rights party, and that Ronald Reagan never happens.

- 2000: We can only imagine what might have happened with Al Gore in the White House, given that he understood the threat posed by global warming at a time when bipartisan action might still have been possible. Meanwhile, George W. Bush involved the United States in two wars, steered the Republican Party rightward, and most certainly paved the way for the elections of both Barack Obama and Donald Trump.

- 1860: It led to the Civil War. And the Civil War either changed everything (or, in some cases, dramatically accelerated changes that were already underway).

We did not include 2020 because that story is still being written, and there's no way to make even a preliminary judgment until, at very least, the election of 2024 is in the books.

As to the least consequential election, we will go with 1888. Benjamin Harrison was the winner. Grover Cleveland was the loser, but came back in 1892 to win a second term. And neither Harrison's term nor Cleveland's second term was particularly successful or particularly consequential. The two men were not all that different in terms of policy and, as already noted, the Gilded Age had a weak presidency.

If readers have alternate suggestions for "least consequential election," we are happy to hear them.

D.A. in Brooklyn, NY, asks: OK, so you explained the election of Jefferson. But how did Madison become Veep then? You can't leave us hanging!

V & Z answer: He didn't, Aaron Burr did, since he was legally either the first-place finisher or the second-place finisher, and so entitled to one of the top two slots. As you can imagine, the Jefferson-Burr relationship was frosty. It made LBJ and JFK look like best friends. And in 1804, Jefferson took his chance to boot Burr and replace him with George Clinton. This was, of course, before Clinton recorded "Atomic Dog."

James Madison became Secretary of State (a.k.a. "president-in-waiting"). And when Madison succeeded Jefferson in the White House, his VP was... George Clinton.

M.H. in Seattle, WA, asks: Reading your piece on Rutherford B. Hayes and the end of Reconstruction made me think that 10 or so years doesn't seem like a lot of time for rebuilding, especially after a Civil War. How does the reconstruction following the American Civil War contrast with post-war efforts following other conflicts? The Marshall Plan seems like an obvious contrast, but Japan, South Korea, Afghanistan and Iraq also seem relevant. Do you think the South was given as much consideration as the losers of other wars?

V & Z answer: At risk of overgeneralizing, we're going to suggest that there are basically two kinds of reconstructions. The first happens when the people who instigated and led the war in question are largely or completely swept aside and are discredited, such that help with rebuilding is welcomed by most or all of the remaining citizenry. This was the situation in postwar Germany, postwar Japan, etc.

The second happens when the leaders of the war in question are not swept aside, are not discredited, and are still present. In this circumstance, those folks constitute a resistance, and they tend to win others to their banner, even if some citizens welcome the assistance of the rebuilders. It is very difficult and very expensive to sustain a reconstruction of this sort, and they are usually only moderately successful, if that. The postwar South and Afghanistan would be in this category.

And so, you're right that a decade or so wasn't enough to completely rebuild and reimagine the South (and there were definitely people who had dreams of a "New South"). However, the issue was not that the South did not get enough consideration, it's that most white Southerners—including the many leaders of the rebellion who remained alive and retained some amount of political power—actively resisted, eventually causing the North to throw in the towel.

R.C. in North Hollywood, CA, asks: In your "Slow-Moving Coup" summary of the 2000 election, you wrote that Al Gore would have won Florida by thousands of votes had a full statewide recount been conducted. What's your basis for saying this?

V & Z answer: That was basically the last paragraph of the night, and it wasn't as clear as it should have been. There were several studies of the actual ballots from Florida, some of them from academics, and a big one funded by a consortium of newspapers. And those studies looked at what would have happened under various conditions (e.g., "What if all ballots with partially punched holes are rejected?"). Under all conditions, Gore picked up votes, anywhere from 40 to 700. Under many conditions, he picked up enough votes to win the state by a narrow margin (100 votes or so).

Meanwhile, since the West Palm Beach returns weren't a matter of judgment, but instead a matter of poor design leading to confusion, there's nothing to be learned from re-examining those physical ballots. However, there have been studies that, making use of statistical methods, estimated how the ballots should have turned out, had they all been marked correctly. Those studies consistently give Gore something like +2,000 votes.

So, what we meant to write was: "If the will of the Florida voters had been accurately polled, Gore would almost certainly have won by a couple of thousand votes."

R.M. in Lomita, CA, asks: Your dire items this week about a potential coup in 2024 got me thinking about what the next steps for democracy-loving individuals such as myself might be. Emigration is an obvious option, but here in California, the idea of secession from the union has been bandied about for many years, and it occurred to me that a coup in 2024 could be just the impetus needed to transform that fringe idea into a real movement.

Drawing from global history, I was hoping you could shed some light on secession movements in the past. What conditions must be in place before a secession movement can gain real momentum? What elements do successful secession movements share? Are there any examples of a country breaking up (which is really what secession is) without bloodshed? Any particular advice for us Californians?V & Z answer: We will start by pointing out that the success rate of secession movements is extremely low. To take California as an example, there have been at least 220 movements to either partition the state or withdraw it from the union. There have been zero cases where it actually seceded or was actually partitioned. Last night was New Year's Eve, and you know what that means in terms of getting a straight answer out of the staff mathematician. However, he seems to be indicating that 0-for-2020 is a success rate of 0.0%.

For a secession movement to succeed, the would-be seceders have to be in the same basic geographic area, and have to be pretty homogenous, usually sharing an ethnicity, a religion, and a basic political outlook. Californians are in the same geographic area, but the state clearly does not meet the other conditions.

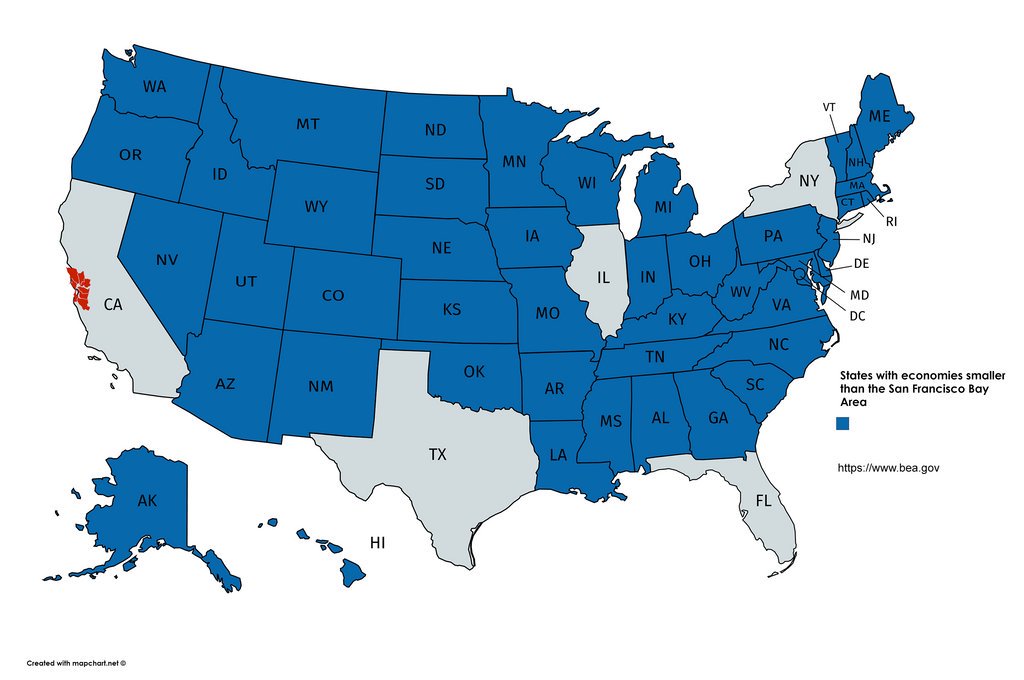

Meanwhile, for various reasons, countries are not eager to let component portions secede. Here's a little map that illustrates just one problem if California were to leave the U.S.:

If you can't read the legend, it shows all the states whose GDP is less than that of the San Francisco Bay area. And that doesn't even include California's massive agricultural output, or the economic activity in the twice as populous southern portion of the state. Indeed, by itself, California has a more productive economy than all but four or five nations. Its GDP is about $3.2 trillion, which is only surpassed by the U.S., China, Japan, Germany and, depending on who you ask, possibly the U.K. There is no way the U.S. government is going to let California walk without a fight.

And that brings us to something else a secession movement needs: force, or the threat of it. Most commonly, secessionists have to back their move with actual violence. On rare occasions, they can persuade the nation they are departing that massive violence will be in the offing if they are not allowed to go. We doubt that California is quite in a position to take on the rest of the U.S., nor that the will exists to do so.

In short, California is going to be a U.S. state as long as there is a U.S.

M.U. in Seattle, WA, asks: In your item about Oprah Winfrey damning Dr. Mehmet Oz with faint praise, you began with a tale of Constantin, comte de Volney, writing: "One of the comte's first stops on his American tour was Mount Vernon, where he asked George Washington, who had just concluded his term as president, for a letter of introduction and recommendation." Can you explain what this custom of having or asking for a "letter of introduction and recommendation" was?

V & Z answer: At that time in human history, people were particularly concerned with status, and with drawing clear lines between social classes. Some nations had caste systems of various sorts. Others had noble titles. Still others had hierarchies built around religion.

The United States did not have these things, at least not formally. However, there were other ways to communicate one's status. One was through conspicuous displays of wealth. A second was through association with people of high status. And a third was adherence to rules of etiquette, since only the "refined" folks knew about and understood those rules. (Louis XIV, for example, famously kept his nobles on their toes by constantly changing the etiquette rules, leaving them without enough time and energy to do things like plot rebellions).

The presentation of letters of recommendation (and, for that matter, calling cards) checked all three of these "signifiers of status" boxes. Most obviously, the letters allowed people to associate themselves with people of high status. Meanwhile, calling cards in particular could be printed on paper that was clearly expensive, thus allowing the wealthy people to display their status. And finally, the exchange of calling cards and letters had a whole ritual involved (that usually involved multiple days of exchanges before a face-to-face meeting). This was an opportunity for a person to display their mastery of the rules of etiquette.

M.B. in East Providence, RI, asks: I was wondering if you could recommend a book on the American Civil War that covers the history leading up the war being declared/secession happening in addition to context for the most important battles during the war.

V & Z answer: Well, there's James McPherson's Battle Cry of Freedom. It won the Pulitzer Prize, is a real page-turner, and covers the lead-up to the war and the military situation as fully as a single volume plausibly can. There are two issues, however. The first is that it was written more than 30 years ago, and so is missing some of the stuff that scholars have been working on since then. Most obviously, it basically has nothing about the Lost Cause and how the memory of the war was used by people after the war was over. The second issue is that it's close to 1,000 pages, which is a bit much for some people.

Alternatively, consider The American War: A History of the Civil War Era. It also covers the subjects you asked about, and is also well written. The two scholars who authored the book have been leaders in the discussion over Civil War memory (Gary Gallagher does the Lost Cause, and Joan Waugh wrote a book on the memory of U.S. Grant), so they certainly get that element into the book, which is only 5 years old. And it's a more manageable 304 pages.

Full disclosure: McPherson is an acquaintance of (Z), while Gallagher and Waugh were both members of his doctoral committee. However, his personal relationship with the trio has no effect on his recommendation; either a book is good or it isn't.

Gallimaufry

R.C. in Des Moines, IA, asks: Why would Prince Charles not keep Charles (III) as his regnal name, as opposed to switching to something like George VII, as you predict?

V & Z answer: Most of the recent monarchs of the U.K. have switched names upon assuming the throne. It's an opportunity for a fresh start, and also allows them to emphasize continuity with the past and the historicity of the monarchy. That's a useful sentiment given that "get rid of the monarchy" sentiment tends to flare up in the U.K. from time to time.

The only monarch since Victoria who did not change names is Elizabeth, although she happened to have the same first name as one of the most popular monarchs in English history, so a change was perhaps a little less necessary. It's true there have been two Charleses, but the last one was nearly 350 years ago, while the Georges are much more recent (and, in fact, George VI is in living memory for some Britons).

We also imagined that Charles might think about the coronation headlines from the British tabloids, and might be leery of "Bonnie King Charlie" or "The Merry Monarch" (that was Charles II's nickname).

Charles also has two other names he could pick from, if he wants to stick with ones he's already got. We seriously considered that he might go with Philip, in honor of his father. We did not seriously consider the possibility that he might go with King Arthur, as the tabloids would definitely have a field day with that.

J.C. in General Trias, Cavite, Philippines, asks: Your statement that most or all of your readers can remember the 2000 Election got me wondering—can all of your readers remember the 2020 Election? Who's the youngest reader that you have? Taking responses at face value, with the acknowledgment that perhaps a parent would have to write in locum pueri, do you have any political savant readers who had not yet reached the age of cognizance in 2020?

V & Z answer: We are aware of a few teenage readers, and we also know of teachers who have their students read the site, or selected articles, at least. So maybe we shouldn't have written that. Let's see what we can learn, however, about both our youngest and oldest readers. If you are below the age of 20, or above the age of 85, or you know a reader of the site who is, could you send in your/their age, initials, and city? We'll reveal what we learn as part of an item we have planned for Tuesday.

Previous | Next

Back to the main page