A couple of weeks ago, we solicited questions from readers about the ins and outs of British politics. Our regular British correspondents—G.S. in Basingstoke, England, UK; A.B. in Lichfield, England, UK; and S.T. in Worcestershire, England, UK—have been kind enough to answer. A few of the questions, and thus the answers, were pretty meaty, so we're going to split this up over the rest of the week. The first entry:

M.M. in San Diego, CA, asks: Why doesn't the Liberal Democratic Party have more appeal for British voters? It seems to be the party that most resembles the liberal wing of our Democratic Party. Did their leadership do something regrettably stupid? Or don't they have much of a message? Or is it something so British it just doesn't translate well into American politics?

G.S. answers: My fellow Britons may give more historical context than this, but the Liberals' current lack of popularity can be traced to one single event, in my view. On May 6, 2010, a general election returned a "hung parliament"—that is, no one party had an overall majority. This is relatively unusual in the U.K. on account of our first-past-the-post system. The Conservatives, then under David Cameron, formed a coalition with the Liberals, who had obtained a rather healthy and king-making 60 seats under a young and dynamic leader named Nick Clegg. Their 60 seats were enough to put Cameron into Number 10. The "bromance" seemed to work quite well, and Clegg was given the post of deputy PM, with many of the Liberals' policies legislated for in this Parliament.

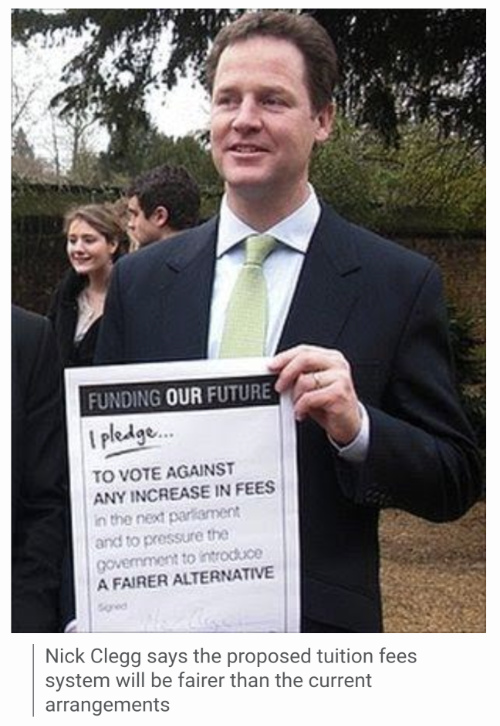

Here's the problem (see attachment):

Nick Clegg's popularity was largely due to young voters, who, like in America, tend to be more liberal. Clegg had made a very noisy and public pledge that he would not, under any circumstances, raise university tuition fees, which had been introduced under the Labour government. Well, you can guess what happened next. The Faustian bargain Clegg made with Cameron required he renege on this pledge; his base, who were nothing like as forgiving as, say, those who haven't seen a wall built, deserted him, despite much of the Liberal manifesto being enacted. The Liberals went from 57 seats to 8 at the 2015 election, and in 2017 Clegg himself lost his seat. He currently works justifying Facebook's policies to a skeptical world, which explains a lot, in my view.

There have been a series of bland and uninspiring leaders ever since, and the Liberals have never really recovered.

A.B. answers: Truth in advertising: I'm a member of the LibDems, and have been a local election candidate for the party in the past (no, I didn't win). But I'll try and give as unbiased an answer as possible—or at least try to telegraph my bias where it's overt.

There are two broad answers to this, one long-term and structural, one more recent and political.

The long-term structural answer is that first-past-the-post voting systems, as used in the U.K., U.S., and Canada, tend to make it difficult for third parties to gain traction in the political landscape. It's the classic "Why waste your vote on a third party?" paradox. The LibDems in the U.K. and the NDP in Canada show that it's possible for a third party to gain some level of traction—the U.S. system seems more institutionally hostile to the existence of third party—while the Bloc Québécois in Quebec and SNP in Scotland show that parties with strong regional/nationalist core votes can be successful within their home region; but the electoral system tends to favor a duopoly of a main left of center national party and main right of center national party, leaving little space for a centrist party. It will come as little surprise that the LibDems are in favor of reforming the electoral system and replacing first-past-the-post with a form of proportional representation, simultaneously acknowledging the obvious self-interest while arguing it would be fairer for the country as a whole.

The recent political answer is that the LibDems were punished electorally for their decision to enter a coalition with David Cameron's Conservatives in 2010, and the compromises they had to make as the coalition's junior partner. They've never quite recovered (though forgive me for noting as a party activist that the country was manifestly better governed during the 2010-15 coalition than it has been since). Before the 1997 general election, when former LibDem leader Paddy Ashdown was negotiating with Tony Blair over some form of post-election alliance (neither leader quite believing that Labour would go on to win in a landslide), Ashdown argued that proportional representation was a necessary precondition to the LibDems agreeing to a formal coalition because the inevitable decline in popularity faced by all governments over time would threaten to wipe out the smaller party. Just over a decade later, his judgment was proved correct.

S.T. answers: It is one of the great conundrums of U.K. politics, especially given that attitude surveys constantly show that on many issues LibDem policies get a favorable response from the British public. The biggest reason for the LibDems' lack of success has to be the first-past-the-post system. This does not necessarily cause a problem if votes are geographically concentrated, as the SNP has proved in Scotland in the last three General Elections, but the LibDem support had traditionally been evenly spread and that has resulted in lots of second places but relatively few victories. Even in the 2005-10 elections when national support was well over 20%, seats won maxed out at 62 out of 650. This lack of success is self-reinforcing and has allowed the two largest U.K. parties to claim that a vote for the LibDems is a wasted voted as they "never win." This is amplified by the procedures in Parliament which give very little power or standing to anyone outside the government and opposition parties. This also means the media concentrates on Labour and Conservative parties too.

It must also be admitted that there appears to be an underlying distrust of coalitions among the U.K. electorate and this was enhanced by the LibDems' period in coalition with the Conservatives in 2010-15. Then LibDem leader Nick Clegg made something of a hash of this opportunity, particularly over the issue of student tuition fees. His 2015 call for the LibDems to continue to receive votes, to moderate the actions of Conservatives and Labour, fell on deaf ears and the LibDem vote plunged, leaving them with just 8 MPs. There is some evidence of rebuilding, particularly at the local level, but with their platform in parliament nearly annihilated, their ability to recover—outside of by-elections—is sorely tested.

R.H.D. in Webster, NY, asks: King Charles III has to be mortified to see his country become a global embarrassment with their recent political turmoil. Surely, he didn't sign up for this when he took the throne.

Now, I know the British monarch has to grant permission for a P.M. to form a government, and gives an annual speech when Parliament commences. But is there anything else the King can do to step in and bring some stability and sanity for his subjects?A.B. answers: The short answer is "No."

The longer answer: A British monarch can only act on the advice of their ministers; they cannot act independently. Even the constitutional process of Royal Assent—whereby the Crown signs off on a bill to make it a formal act of Parliament—is now almost completely removed from the monarch's person. It's widely known that the last monarch to refuse assent was Anne, in 1708 (though even then she was acting on the advice of her ministers). It's less well known that the last monarch to grant assent in person was Victoria, in 1854.

The monarch invites the individual who can command a majority in the House of Commons to form a government. King Charles has no discretion in that process, and it's up to the individual parties to decide who is selected as their leader, and up to Parliament to decide who can command a majority (the Conservative Party cleaned up an anomaly that inadvertently gave the monarch some residual discretionary role back in 1957). It is generally believed that almost the last remaining discretionary power that the monarch has in this process is the right to refuse a request to dissolve Parliament under two narrow circumstances: (1) if the current Parliament is "vital, viable, and capable of doing its job" or (2) if the monarch believes they can "rely on finding another prime minister who could govern for a reasonable period with a working majority in the House of Commons." These are the "Lascelles Principles"—and it says a lot about the U.K.'s constitution that these crucial points were defined in a then-anonymous 1950 letter to The Times written by George VI's private secretary (rather than in, say, an act of Parliament). However, it's also generally held that the government should go out of its way to avoid putting the monarch in the position of having to use the Lascelles Principles—though there was some idle chatter about Charles potentially refusing a request from Liz Truss to dissolve Parliament if she attempted to do so between her resignation and the appointment of Rishi Sunak.

S.T. answers: A.B.'s response covers this perfectly.

S.H. in Hanoi, Vietnam, asks: What precisely does a "no confidence" vote mean, and what are its mechanics? One of the bits from the Truss endgame that I couldn't follow was that many Tories were upset about whether a bill to "consider legislation to ban fracking" was a no-confidence vote. I would have assumed a no-confidence vote was simply that—one whose verbiage was along the lines of "do you still want this person to be your party's standard-bearer?" But apparently not.

A.B. answers: There are two separate no confidence paths, one for Parliament to vote on the government, and one for parties to vote internally on their leader. This caused some confusion in the last days of Boris Johnson's government.

A government must be able to form a majority in the House of Commons. In other words, it must show it commands the confidence of the House. A general election can be triggered if there is a vote demonstrating that it has lost that confidence; not necessarily any vote, but a vote specifically designated as proving that confidence has been lost. The most common mechanisms here are:

- The opposition or government calls a confidence motion. These rarely succeed since opposition motions tend to unite the government party, and government parties typically don't call confidence motions they're likely to lose. The last successful opposition motion of no confidence was in 1979, when Margaret Thatcher called a motion that James Callaghan lost by a single vote—triggering the election that brought Thatcher to power. Prior to that, the last successful no-confidence motion had been in 1924.

- The government declares that a vote on a particular bill or motion is doubling as a confidence motion; this is usually done to force members of the governing party to help pass a particular piece of legislation (for example, John Major using this maneuver to pass the EU Maastricht Treaty in 1993), but can backfire. Liz Truss's catastrophically handled attempt to turn an opposition motion on fracking into a confidence motion—therefore forcing her MPs to vote against a 2019 election manifesto commitment—is a case in point; it was the final straw that brought her down.

Separately from these parliamentary processes, individual parties can hold confidence votes in their own leadership. If they lose, then the leader will have to resign—though this need not trigger a general election if the governing party replaces its leader but still has a majority in Parliament. These need not be definitive. Boris Johnson won the June 2022 internal party confidence vote in his leadership, only to be forced out a month later due to mass resignations by government ministers in protest against the latest scandal to engulf his government.

S.T. answers: Again, I cannot add to A.B.'s answer.

Tune in tomorrow for another installment! (V & Z)