This would ideally have run yesterday, but December is the most intense phase of the teaching calendar (well, December and May-June). so, it runs today. Here are the previous entries:

The last group of non-presidential slogans focused on movements that were progressive in their nature. However, American culture and politics have always had a regressive/reactionary element, too. And today, we take a look at the rallying cries of some of those groups of people:

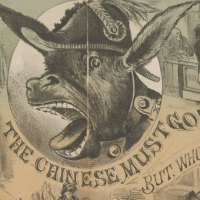

The Chinese Must Go! (1850s): The California gold rush began in 1849. Chinese immigrants, looking to make their fortune, began to arrive in large numbers in 1850s. Anti-Chinese bigotry reared its ugly head... well, pretty much the day after the Chinese began to arrive. The notion was that the new arrivals were taking gold that "belonged" to the white man. Hence the slogan "The Chinese Must Go."

Of course, the gold rush eventually came to an end. But the anti-Chinese sentiment most certainly did not. Indeed, "The Chinese Must Go" reached the peak of its influence in the 1870s thanks to the rabid xenophobe Denis Kearney. Kearney was a moderately successful businessman who decided to transition into politics, and who decided the key to power was telling working-class white men that immigrants were to blame for all of their problems. Obviously, the Kearney playbook couldn't possibly work today. At very least, someone like that couldn't be elected president. Right?

There had been anti-immigrant political movements before Kearney and his followers came along, but this was arguably the first of those movements to achieve lasting success. After a white, working-class-led riot in San Francisco in 1877, the anti-Chinese forces were able to compel the state of California to ban Chinese immigration in 1879, and then were able to successfully lobby the federal government to follow suit in 1882, with the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chinese people could not again immigrate to the U.S., at least not legally, until the 1940s.

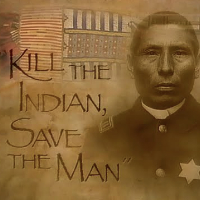

Kill the Indian, Save the Man (1902): This is not about literal killings. The U.S. government did plenty of that when it came to the Native Americans, of course, but didn't really have a slogan for it. There was Phil Sheridan's line that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian," but that was more a statement of mid-19th century U.S. Army policy than it was a slogan.

The "killing" in "Kill the Indian, Save the Man" referred to Native American culture. Brig. Gen. Richard Henry Pratt was the long-serving superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (perhaps best known as the alma mater of super-athlete Jim Thorpe). And by the standards of his day, Pratt was actually a liberal. In fact, he was basically Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) liberal. In 1902, at a time when segregation was both the custom and the law of the land, Pratt lambasted racial bigotry and wrote: "Association of races and classes is necessary to destroy racism and classism." Interestingly, this is the first known use of the word "racism."

The problem, from a modern vantage point, is Pratt's belief that to overcome racism, it was essential to erase races. Well, non-white races, at least. And so, in service of equality as he understood it, he proposed to transform his Native American students into white men and to eliminate all vestiges of tribal identity and culture. Today, of course, that is called cultural genocide. It is difficult to quantify exactly how much harm was done to Pratt's charges, who were often forcibly taken from their parents. But it was surely substantial.

Better Dead than Red (1930): There were two major "red scares" in U.S. history. The first came during and after World War I, largely in response to the Russian Revolution. That got the ball rolling on rabid anticommunism. And it was in response to that rabid anticommunism that The Nation's editorial board published a sarcastic piece that concluded this sentence: "As for those weaklings who may fall by the wayside and starve to death, let the country bury them under the epitaph: Better Dead than Red."

Again, that was meant ironically (which is clear from the original editorial; you can read it here, if you wish). However, when the second red scare began after World War II, Joseph McCarthy and other anti-communist zealots appropriated the phrase and began to use it unironically.

The slogan, and the underlying sentiment that propelled it to prominence in the 1950s, helped fuel the belief that it was worthwhile to fight two wars (Korea and Vietnam) to "resist" communism. And those wars did much harm to the U.S., not to mention those two nations and the rest of the world.

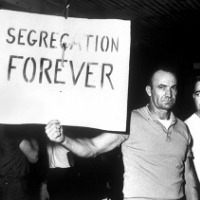

Segregation Now, Segregation Tomorrow, Segregation Forever (1963): This might be the most famous slogan of the four in this set. Alabama governor George Wallace may have been a bigot, but he knew how to turn a phrase. And this phrase from his inaugural address was quickly seized upon by anti-Civil Rights Movement Southerners.

Undoubtedly, the slogan affected the thinking of white Southerners and inspired their continued resistance to integration. That includes violent resistance; it's fair to suspect that some of the killings that took place after 1963, from the Freedom Summer murders to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., were at least partly fueled by Wallace's fiery words. That said, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed a little over a year after Wallace coined this phrase, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed a little over 2 years after. Further, when federal troops showed up to integrate the University of Alabama, Wallace uttered his little catchphrase and then... got the hell out of the way. So, the impact of this particular slogan is nebulous.

Recall that the standard of judgment here is impact, not necessarily positive impact. In any event, the ballot is here. The next set of slogans will cover presidential campaigns from World War II to the end of the 20th century. (Z)