Previous | Next

New polls:

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill Is a Go

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) had to do so much whipping on Friday that they're thinking of casting her in the new Indiana Jones film. But in the end, the House managed to pass the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill, 228-206. The measure heads to Joe Biden for his signature, and he's said he will apply it promptly.

The vote was not entirely a party-line affair. There were 13 Republicans who were "yeas" on the measure: Don Bacon (NE), Brian Fitzpatrick (PA), Andrew Gabarino (NY), Anthony Gonzalez (OH), John Katko (NY), Adam Kinzinger (IL), Nicole Malliotakis (NY), David McKinley (WV), Tom Reed (NY), Chris Smith (NJ), Fred Upton (MI), Jeff Van Drew (NJ), and Don Young (AL). There were also six Democrats who were "nays": Jamaal Bowman (NY), Cori Bush (MO), Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY), Ilhan Omar (MN), Ayanna Pressley (MA), and Rashida Tlaib (MI).

The six Democratic "nays" are all outspoken progressives, and their vote reflects a divide that developed within that part of the Democratic caucus. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), who is the head of the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC), got a phone call on Friday from Joe Biden, who also spoke to the CPC as a whole. Further, five leaders of the moderate faction of the Democratic Party issued a memo that promised support for the bigger reconciliation bill "in its current form other than technical changes, as expeditiously as we receive fiscal information from the Congressional Budget Office—but in no event later than the week of November 15." All of this was enough to persuade Jayapal and a fair number of her CPC colleagues to drop their demand that the House vote for the smaller bill and the bigger bill at the same time.

These developments, coupled with the reports out of Washington over the course of this week, suggest that the reconciliation bill is very close to the finish line. There's little chance that Jayapal & Co. would have yielded unless they knew basically what's in the big bill, and that the bill's in line to get the votes it needs in the Senate. "Don't count your chickens until the eggs are hatched," and all that, but it's hard to see how the blue team doesn't bring bill #2 in for a landing sometime in the next week, especially since they don't have to bicker about when to vote on bill #1 anymore. (Z)

Saturday Q&A

As you might imagine, Tuesday's elections—and some of the political dynamics they hint at—were a popular subject this week.

Current Events

S.C. in Mountain View, CA, asks: On her show Wednesday evening, Rachel Maddow pointed out that, at least as far back as the election of George H.W. Bush, whenever a new President was elected, their party lost both the New Jersey and Virginia governorships the following year. (She said that what made this year significant wasn't that the Democrats lost Virginia, but that they won New Jersey.)

I haven't checked her work, so I don't know if that trend really holds or how far back it goes, but is there any underlying meaning to such a trend? I suppose one could say that, since Presidents hardly ever deliver everything they promised in their first nine months of office, their supporters in those two states are disheartened so don't vote, their opponents are out for revenge so do vote, and swing voters who voted for the party in power decide to give the other party a try.V & Z answer: Maddow has the trend correct. The last time a political party elected a new president and then also won the next gubernatorial election in Virginia was in 1968 (Richard Nixon) and 1969 (Linwood Holton). The last time a political party elected a new president and then also won the next gubernatorial election in New Jersey, prior to this year, was in 1980 (Ronald Reagan) and 1981 (Thomas Kean).

As to the underlying meaning, it surely has to be what you propose, namely that voters from the party that holds the White House become complacent and/or disappointed that more isn't getting done, while voters from the party that does not hold the White House are smarting and looking to push back against the administration. Also, because of the timing of these two states' gubernatorial elections, the party out of power has just had 10 months to practice and to hone its lines of attack. Not so with the party in power. Don't forget that nobody outside of academia had ever heard of critical race theory 10 months ago.

B.L. in Hudson, NY, asks: You listed a few reasons why we should be careful about reading too much into Glenn Youngkin's (R) win in Virginia, among them "McAuliffe is intimately associated with the Clintons, who are currently pretty toxic." Why are the Clintons more toxic than usual right now? I know that Hillary, in particular, is pretty polarizing in general, but did I miss some important recent news item?

V & Z answer: You did not miss any important news item; it's just a general truism based on Hillary's (mostly invented) scandals and Bill's real-life behavior (which became much more problematic after #MeToo). Presumably they will remain damaged goods for the rest of their natural lives, as they likely don't have enough time left to disappear and then re-emerge in a decade as wise political elders (à la Herbert Hoover, Richard Nixon, and Barry Goldwater).

The dead giveaway that they are seen as a liability is this: McAuliffe could have had both of them campaigning for him with a single phone call (except during Bill's brief recent hospitalization, of course). But while Barack Obama, Kamala Harris, Joe Biden, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) and a gaggle of other Democratic luminaries held events for McAuliffe, the Clintons were nowhere to be found.

M.A. in West Springfield, MA, asks: You wrote: "Since [India] Walton won the primary, she is presumably the favorite again, especially with the backing of much of the Democratic establishment."

Having read this website for more than a decade, I know you guys do your research. I find it really implausible that you're so out of the loop that you're unaware Walton trails Brown in polling by close to 20 points. What gives? Did you know something I don't?V & Z answer: It is often difficult to get good information about local races. Further, those races are often unpolled or under-polled. We couldn't find any polls of that race before we published that (and have since only found one). So, we made our best guess based on: (1) Walton's primary win, (2) endorsements, and (3) the generally low odds of someone winning a write-in campaign.

We tried to make clear with our wording that we were just speculating. If we have some firmer basis for a prediction than just our best guess, we try to be clear about what that something is (e.g. "polls of the race indicate X, so that suggests Y").

C.J. in Lowell, MA, asks: What insight can you give on what seems to me like the two parties' differing abilities to get stuff done (or can you tell me why I'm wrong)? It has been frustrating watching the Democrats fight with each other over the size and scope of spending. It's like they are playing the roles of both parties, since the other "party" has become a nihilist cult of personality. Why do I get the sense that if the numbers were reversed, whereby Republicans had a tiny House majority, 50 Senators, the presidency (and, thus, the vice presidency with its tie-breaking Senate vote) they would have been able to shove through their agenda a long time ago? Why does it seem that when the Republicans have majorities, Democrats are powerless to stop them, whereas when Democrats have majorities, Republicans still seem to have a veto? Its like Danny Concannon asked in The West Wing: "Why are Democrats always so bumfuzzled?"

V & Z answer: As of January 20, 2017, the Republican Party controlled the White House, 54 Senate seats, and 241 seats in the House. And with a much greater margin for error than the Democrats have now, they got very little done. The red team failed to repeal (much less replace) Obamacare, and in very high-profile fashion. They got a bunch of judges approved (which the Democrats are also currently doing), and they passed the 2017 tax bill. That's about it.

So, we think you might be suffering from a little recency bias, since the sausage-making of the Democrats is right before your eyes right now, whereas the (largely ineffective) sausage-making of the Republicans is a few years in the past. If the Democrats are having a harder go of it, then we would say it's due to four things: (1) they have a more ideologically broad coalition, (2) they don't have a president who will put members' careers, and very possibly their lives, in danger if they fail to fall into line, (3) they are more aspirational than the Republicans, and are trying to achieve more stuff, policy-wise, and (4) they have such a small margin that every Democrat in the Senate gets a veto, and so must be accommodated.

E.W. in Lancaster, OH, asks: I was surprised to see you list "gas prices are crazy" among the reasons for Joe Biden's struggles. I keep asking people for evidence that gas prices are somehow higher than usual in any meaningful way. No one seems to have any information. I relate the story that my last year of undergrad (2010); our per gallon price for gasoline here hit $4.09, the highest I have ever paid for gasoline. It came down from that high and has been between $2 and $3.50 for basically that whole period. Honestly, I think it was under $2 for a bit as well. It has been $3.25 or so lately, after being between $2.50 and $3 most of last year. Of course, I know in St. Louis or Seattle or similar, gas prices are higher than here in general, topping $5 or $6. But relative to past prices, is there any evidence anywhere in the country that gas prices have gone up appreciably in 2021 under Joe Biden?

V & Z answer: This did not get all that much attention, but back at the start of 2020, there was actually a glut in the oil market, and American producers were in big trouble. So, Donald Trump got on the phone and convinced OPEC to cut production. It's arguably the only deal that the guy who "wrote" The Art of the Deal made by himself during his time in the White House. This story got drowned out by the pandemic, and then by the fact that it didn't work out so well, long-term, because gas prices have indeed spiked.

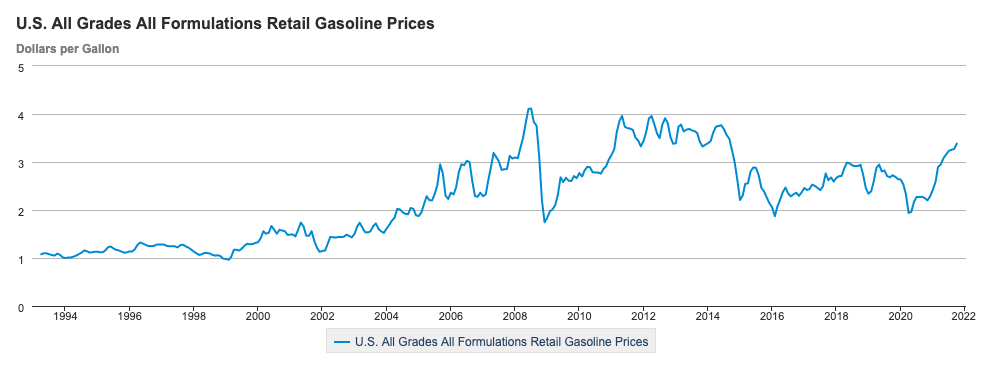

The Department of Energy keeps statistical information on this, which is posted to their website. Here it their graph of the average price of a gallon of gas over the last 25 years:

As you can see, your memory is correct, excepting that it may have been your sophomore or junior years rather than your senior year that gas prices were highest. At the moment, prices aren't as high as they were then, but most people aren't 10-year thinkers. Instead, they are "what have you done for me lately" thinkers, and in the last 10 months (i.e., the Biden presidency), prices have consistently risen.

It does not help that, as you point out, there are state or local taxes added on top of the cost of the gas, such that the price has crossed $4/gallon, $5/gallon, or even $6/gallon in many places. In New Jersey, for example, the 42.4 cents/gallon that is added is just enough to push the current average price over $4/gallon. People take particular notice when lines like those are crossed, which is why so many items at the store cost $1.99 or $3.99 or $6.99.

R.S. in San Mateo, CA, asks: I'm confused by Judge Tanya Chutkan's position on Donald Trump's lawsuit claiming executive privilege. Congress is requesting government documents from the National Archives, which the current executive branch does not oppose. I understand Trump's claim, but it seems like he either has executive privilege or he doesn't. Either Congress has a right to the documents or they don't. Under what criteria can the judge view the request as too broad and potentially narrow it?

Also, what is the process by which protected documents in the National Archives eventually become public? Is it automatic after some period of time, or would a future administration need to proactively release them?V & Z answer: Trump's lawyers have based their argument on the notion that he is entitled to privacy. That's not true with his official work, but it could be true if he discussed ongoing legal cases in the Oval Office, or perhaps his health. So, there may be some things that would rightly be held back.

As to the process, when a document is classified, it is supposed to be assigned a date on which secrecy will no longer be necessary (the default is 10 years). If a document is scheduled to remain secret beyond 10 years, it is supposed to be reviewed on a regular basis to make sure that secrecy remains necessary. At the 25-year mark, there are only nine types of information that may remain secret, namely information that would:

- Reveal the identity of a confidential human source, a human intelligence source, a relationship with an intelligence or security service of a foreign government or international organization, or a nonhuman intelligence source; or impair the effectiveness of an intelligence method currently in use, available for use, or under development

- Reveal information that would assist in the development, production, or use of weapons of mass destruction

- Reveal information that would impair U.S. cryptologic systems or activities

- Reveal information that would impair the application of state-of-the-art technology within a U.S. weapon system

- Reveal formally named or numbered U.S. military war plans that remain in effect, or reveal operational or tactical elements of prior plans that are contained in such active plans

- Reveal information, including foreign government information, that would cause serious harm to relations between the United States and a foreign government, or to ongoing diplomatic activities of the United States

- Reveal information that would impair the current ability of United States Government officials to protect the President, Vice President, and other protectees for whom protection services, in the interest of the national security, are authorized

- Reveal information that would seriously impair current national security emergency preparedness plans or reveal current vulnerabilities of systems, installations, or infrastructures relating to the national security

- Violate a statute, treaty, or international agreement that does not permit the automatic or unilateral declassification of information at 25 years

At the 50-year mark, the list drops to just #1 and #2. And at the 75-year mark, presidential permission is required in order to keep a document classified any longer.

Note that these rules are set by executive order, and so could be changed by Joe Biden or any other president at their discretion.

Politics

M.M. in Seattle, WA, asks: Recent polling results show that 70% of Americans believe the country is going in the wrong direction. But without knowing the party of the respondents, the answer is meaningless (it seems to me). Republicans may think we're headed in the wrong direction because of white replacement theory, vaccine mandates, and rigged elections, while Democrats may believe it's because of voting rights suppression, Roe v. Wade, and the increase in right-wing extremism. Am I missing something?

V & Z answer: You're not missing anything. When an election (particularly a presidential election) is not close, and when candidates are not yet known, "Is the country headed in the right direction?" is a means of taking the pulse of the electorate, and hinting at what might happen in the next election if current trends hold.

That said, it's a very crude tool, as you point out. You don't get a sense of why people feel that way (unless the crosstabs tell you), and you also don't get a sense of what they might do based on that sentiment. When Donald Trump ran for reelection, only 35% of Americans said the country was headed in the right direction, and yet 47% of voters went for him. Clearly, there were some people who voted for him despite thinking the country is headed in the wrong direction. Maybe they felt Joe Biden would take it in an even wronger direction.

To the extent this sort of polling is useful, it is in comparison to past polls on the same question. In other words, if we go from "55% think the country is headed in the wrong direction" to "70% think the country is headed in the wrong direction," that is surely bad news for the party in power, and suggests that some of that party's voters may not be motivated to get to the polls the next time there's an election.

A.S. in Enfield NH, asks: Can you better explain the "vote the bums out" phenomenon? Taking the current Democratic congress as an example, it seems clear that they would have an easier time passing their agenda if they had larger majorities in the House and Senate. In that case, why would anyone who supports the Democrats' agenda react to their struggles at governing and decide that the solution is to vote for more Republicans (again, this is assuming the "vote the bums out" people support the bums' agenda)?

V & Z answer: The problem is that humans are programmed to respond to instant gratification. And so, when it comes time to vote, many of them ask the question that Ronald Reagan proposed back in 1980: "Am I better off than I was X years ago?" It was 4 years in his original formulation, but it works just as well for 2 years.

It is possible that loyal members of a particular party might conclude that they just need to give their party a little more time and a little more support. But those are not the folks who swing close elections. It's the "what have you done for me lately?" voters who do.

With that said, the "throw the bums out" phenomenon is driven a less by people voting to punish the party in power, and a more by people who support the party in power becoming complacent or disillusioned and not bothering to vote at all. That's basically what happened in New Jersey this week; it's not that vast numbers of voters turned against Gov. Phil Murphy (D), it's that a lot of his base didn't show up to the polls.

J.M. in Seattle, WA, asks: Given the results of the elections this week, I had a question about voting habits. It seems like most midterms seem to go against the party in the White House, which makes sense to me—I think a lot of people believe the grass is always greener and it's a lot easier to complain and promise change when you're not in power than when you're the party that owns the problems.

My questions is, has this ever not been the case? I'm 35 and only really have the years since 2004 for my frame of reference. Have there been many periods where most people say "Hey things are good, we want more of this?"V & Z answer: The best way to examine this question is House elections, since those are national, and since every member is up every two years. And the answer that you get, at least from this particular data set, is that "the grass is always greener" is pretty much an evergreen sentiment. In the last century, only three times has the sitting president's party gained seats in the House in a midterm election. It happened to Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 (+9), Bill Clinton in 1998 (+5), and George W. Bush in 2002 (+8).

If the Democrats want to hold the House next year, then, it's going to be a tall order. Their best hope is probably the Clinton model. Roosevelt and Bush made their gains in the face of national crises (the Great Depression and the 9/11 attacks, respectively). Clinton, however, benefited from Republican overreach, as they literally made a federal case out of his extramarital activities (though the actual impeachment came after the election). If the Supreme Court strikes down Roe v. Wade when it announces its decisions in June-July of next year, that could very well generate a backlash that keeps the Democrats in control of the House.

J.B. in Hutto, TX, asks: About a year ago, The New York Times ran a piece loaded with polling statistics suggesting that the vast majority of Americans (80% to 85%) don't follow politics closely or at all. Moreover, these unengaged voters generally felt certain issues, such as hourly wages, were more important than the issues that fired up hyper-partisan issues on either the left or the right. The implication is that the political junkies who never turn off Fox or MSNBC and who post their political opinions on social media every hour are living in a fantasy world divided resembling a Game of Thrones struggle between conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats, while in the real world most Americans are too busy trying to figure out what's for dinner and who's going to pick their kids up from soccer practice to care much about politics.

This data, combined with the results of both the 2020 election and this week's off-year election, reinforce for me the idea that America is neither a left-leaning or right-leaning nation, but fundamentally a centrist nation. Most Americans would just like it if the Trumpers and the woke progressives would both simply shut up and stop interrupting daily life.

Agree or disagree?V & Z answer: Agree a little, but mostly disagree.

To closely follows politics requires a fair bit of knowledge and a fair bit of time. A lot of people either don't have one or the other (or both), or else they are not so inclined. So, we concur that "political junkies" is a small subset, and that most Americans are dialed out most of the time.

However, we strongly disagree that the issues the parties are focused upon are "squeaky wheel" issues designed only to please the outspoken few. Huge numbers of voters really do care about things like global warming, taxes, education, homelessness, healthcare, and the like.

The problem is that, as we have already pointed out today, many people seek instant gratification, or something close to it. And because they are dialed out, they don't fully appreciate that sausage-making is very difficult. When change doesn't come rapidly, they often get angry at the politicians, which is why Congress in particular has an abysmal approval rating. But that does not mean that people don't care about big picture issues or, for that matter, that politicians don't care about bread and butter issues.

D.E. in Lancaster, PA, asks: Senator Manchin (?-WV) once again made headlines with his statement that America is a center-right country (what he actually said was, "This is not a center-left or a left country, we are a center—if anything, a little center-right—country"). A quick Google search to check the accuracy of his statement brought up that this seems to be a perennial question and a question with many answers. Although the several articles I looked at all quoted the same polling, they all differed in their interpretation.

I might be biased, but going all-Trump here with my gut feeling, it seems to be wrong. There's the matter that more people consider themselves Democrats than Republicans. There's the matter that very liberal policies poll very well, so well that they are often double or triple the number that identify themselves as liberal. How can a center-right country be so willing to embrace very liberal/progressive views? Lastly there's the matter that how can we be a center-right country when in the last 20 years we've passed Obamacare and made gay marriage legal, just to pick out two examples. Considering where the country started, it seems if anything we are a left country and there is tons of legislation and amendments to back that up.

So would you guys like to tackle this one? What are we? Am I wrong? Is Manchin wrong?V & Z answer: Manchin's statement is more than a little self-serving, since it implies that he's the most reasonable member of the Senate, as he alone occupies the "middle" of the political spectrum.

In any event, one could write a whole book about this question (and many books have been written about it, of course). However, we're going to give a fairly brief and simple answer for you to consider: Americans, on the whole, like a lot of liberal ideas, from rebelling against the king, to limiting slavery, to granting the vote to women, to Social Security, to Medicaid. However, Americans are also unusually resistant to change. The culture, and the political system, are very much built on conservative ideas about allowing change only very slowly.

In short, there is something of a paradox here, which would help explain why many people support Democratic policies, and yet don't support those policies with their votes. It would also explain why American politics are, on the whole, to the right of European democracies, since most of those are designed to make it possible for the party in power to make changes, as opposed to being designed to slow things down.

S.K. in Sunnyvale, CA, asks: You wrote: "To take another example, BetOnline has Trump at +225 to be elected in 2024 and Biden at +400."

This is not a notation I am familiar with, nor that I recall having seen on your site. Would you mind explaining?V & Z answer: That is the 'murican way of representing betting odds. It means that betting $1.00 on Trump will win you $2.25, and betting $1.00 on Biden will win you $4.00. Europeans (and...uh, oh...Canadians) tend to use fractional odds. The equivalent to +225 is 9/4, and the equivalent to +400 is 4/1.

D.T. in San Jose, CA, asks: You guys do a pretty good job of setting realistic expectations. You often offer predictions with qualifiers such as "This will most likely happen" or "That is still a small possibility."

Many (lower quality) outlets described the Republican success on Tuesday as "shocking." Based on your coverage, I considered it to be merely "a bit unexpected."

Are there any election results, in recent history, that you would have described as "shocking"? How often are you guys caught completely off guard?V & Z answer: There is only one that went against everything we know about politics, and that left us completely shell-shocked: Donald Trump in 2016. That ran contrary to the polling that year, it ran contrary to well-established trends in American politics (like the Democrats' midwestern "blue wall"), and it ran contrary to the fate suffered by Trump-like candidates in the past.

In fairness to us, even Trump's campaign didn't think he had a chance. They did not plan an election night party for him, or write a victory speech for him, because they didn't imagine those things would be needed. There are stories in various media outlets that Melania Trump burst into tears when it was clear Trump was going to win because she didn't expect it and didn't want it.

Civics

K.F. in Framingham, MA, asks: There were a couple major gubernatorial and mayoral elections this year, and that got me thinking about the second-in-command. Different states of have different expectations for the role of lieutenant governor. But what is the history behind referring to that position by that title? Why not vice governor or deputy governor? I think it's interesting how in some cities, too, they have deputy mayors, vice mayors, or no official second in command at all—but I understand that's up to individual city charters.

V & Z answer: Unfortunately, these usages became established far enough in the past that we cannot give you a rock-solid answer. However, we will note that in this context, "lieutenant," "vice," and "deputy" all have the same meaning. So, the use of a particular term likely reflects: (1) what other bodies politic were doing, and (2) which variant rolls off the tongue most easily.

Consider that lieutenant general and vice admiral are the same rank in most militaries (three stars), and yet there are no vice generals or lieutenant admirals. Clearly, the terms that did come into use sounded better when they were first adopted, and then they just spread from there.

F.L. in Denton, TX, asks: With a recent referendum here in Texas, my daughter got the runaround about her voter registration and was, de facto, disenfranchised, even though she had a driver's license with her current address and had consistently voted in the past. I know that the right to vote is implied in several amendments, yet, as far as I can tell, it's not specifically stated anywhere in the Constitution. Do you have any thoughts on this rather glaring omission by our Founding Parents? Or did I miss something?

V & Z answer: The Constitution, in its original form, makes very clear that someone gets to vote, but allows the states to decide for themselves which someone or someones that might be. The Founding Parents did this, of course, because they envisioned a world where only propertied white men would get the franchise.

Since that time, of course, the Constitution has been amended to make clear that voting rights cannot discriminate against women, minorities, or people over the age of 18. Further, the Constitution also makes clear that Congress has the right to step in and overrule the states.

What this all means is this: You're correct that the right to vote is not guaranteed. Texas probably could take away your daughter's franchise if they passed a law that limited the vote based on membership in some non-protected class. For example, if they declared that only people who were born in odd-numbered years are allowed to vote, that might well be legal. The Nineteenth Amendment does not guarantee women the right to vote, it merely says that their right to vote "shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

That said, if Texas or any other state tried something like that, there would be huge blowback and Congress would step in and exercise its right to dictate terms of voting.

History

S.R.G. in Playa Hermosa, Costa Rica, asks: I have long been fascinated by the periods in U.S. history known as the Great Awakenings.

Do you think that a Third Great Awakening is likely in this century? What would you see as the elements of such an event?V & Z answer: The first two awakenings happened when (1) the U.S. faced great challenges, and (2) people turned to religion as (part of) the answer. In both cases, American religion, and in particular American Protestantism, became more accessible so as to appeal to new adherents.

Quite clearly, the country will meet the first prerequisite—great challenges—in the next century. Global warming alone is bigger than anything Americans faced in the 1730s-1750s (First Great Awakening) or the 1790s-1840s (Second Great Awakening). The question is whether or not Americans turn to religion in large numbers in response to global warming (or other crises). At the moment, the trend is away from religion, not toward. This is somewhat caused by the transformation of many churches into far-right political organs, where GOP is #1 and GOD is #2. If church leaders reverse this trend, and start focusing more on nourishing souls, and less on nourishing Republicans' super PACs, then sure, there could be another awakening.

We should note, however, that there is already a period known as the Third Great Awakening (1850s-1930s). Some scholars also argue for a Fourth Great Awakening (1960s-1980s), though that one was focused on the aforementioned greater political activism, and not on greater outreach. So, most scholars reject it as a concept, thinking (correctly, in our view) that it's a very different phenomenon than the other three awakenings.

E.F. in Brussels, Belgium asks: My son is starting college (in Maastricht), studying business, but with a strong interest in history. When discussing the Civil War, I stated that the North was more powerful. He remarked that to him it wasn't surprising that an economy relying on unpaid labor would be inefficient. Among his arguments he noted that a minimum wage seemed to correlate with a better economy.

Is it possible to speculate about whether the absence of slavery would have forced the South to automate cotton planting, picking, etc., much faster? Is it possible that slavery was in fact a drag on its economy? In other words, in addition to being the horrible crime that it was, did slavery also hamper the economic development of the South?V & Z answer: This question has been debated by scholars for centuries. And it may surprise you to learn that it was the racists who argued that slavery was unprofitable, while more progressive scholars argued that it was very profitable, indeed. This is because the racists (most importantly Ulrich Bonnell Phillips) were trying to make the case that white Southerners weren't bad guys who were exploiting the enslaved people, they were actually good guys who were running something of a charitable endeavor meant to help "civilize" those who were enslaved.

As for our answer, we're going to have to turn your question on its side, to an extent. The South's problem was not slavery, per se, it was their commitment to profitable, but hard-to-grow, commodities—first tobacco, then cotton. The reason that the region adopted a slave-based labor system is that no other form of labor worked. Wage earners refused to accept tobacco/cotton-harvesting jobs, as the pay just wasn't worth it, and non-African folks who were forced into various forms of servitude (Native American slaves, white indentured servants) tended to die on the job.

The problem with tobacco, beyond it being difficult to cultivate, was that it ruins the soil. And the problem with cotton, beyond it being difficult to harvest, is that there was a lot of competition from other producers (like Egypt) after about 1850 or so. Slavery made both tobacco and cotton viable for far longer than they otherwise would have been. And Southern slaveowners stuck with slavery because they had so much invested in the system, both in terms of capital, but also in terms of their social system and their culture.

So again, the economic problem wasn't the slavery itself (though slavery is indeed a horribly inefficient labor system), it was that slavery allowed the South to wed itself to commodities that did not have a good long-term future, and then slavery made it hard for the South to divorce themselves from those same commodities. Had slavery been outlawed 40 years earlier, however, it probably wouldn't have led to innovation, since the technology to harvest cotton mechanically was not possible until the 1930s and 1940s. What it probably would have done is led to the much earlier development of sharecropping.

F.S. in Cologne, Germany, asks: What would have happened if the Confederacy had won the American Civil War and conquered the Northern states? Would slavery have been introduced in the Union?

V & Z answer: The Confederacy was not attempting to conquer the North, nor did they have the means to do so. Their endgame, and all they could plausibly hope to do, was to hold on long enough that the federal government accepted secession and stopped trying to make the Confederacy return to the fold.

That said, slavery was tried in the North, and it didn't work. First, because it offended the sensibilities of many Northerners. Second, because there were better economic alternatives that ultimately made slavery an unwise financial choice. So, even if the Confederacy had taken over the entire U.S., they would not likely have been able to introduce slavery to states beyond those with large-scale cash-crop agriculture. In other words, maybe Kansas or California, but not New York or Michigan.

S.B. in Narragansett, RI, asks: Had she been the nominee in 2008, do you think that Hillary Clinton would have beaten John McCain?

V & Z answer: That is a very hard question. On one hand, John McCain was a stronger candidate than Donald Trump. And if he had been running against Clinton, he likely would not have made the mistake of choosing Sarah Palin as his running mate.

On the other hand, the "scandals" that harmed Clinton's 2016 campaign—uranium sales, the Clinton Foundation, Benghazi and, most importantly, the e-mails—all came from her time as Secretary of State. There clearly was (and is) a vast reservoir of anti-Clinton hatred among the nation's Republicans. But that hatred would probably have been harder to channel in 2008, for lack of "fresh" scandals, and also because John McCain wasn't an "attack dog" type of candidate the way Donald Trump was.

There's also the fact that the electorate was very unhappy with the Republican Party in 2008, thanks to the misdeeds of the Bush administration and the state of the economy. So, adding it all up, we think Clinton would indeed have beaten McCain.

Gallimaufry

S.G. in Detroit, MI, asks: On Friday, you had a piece about the Hebrew meaning of Facebook's new corporate name, "Meta." Some of your examples I seem to recall as urban legends, in particular the "Nova," which may have led to a lot of jokes, but didn't actually hurt GM. As a big fan of E-V.com and of urban legends, I'd love to read a deeper dive into whether these well-known stories about foreign branding snafus are fully true or just great illustrative stories about knowing your audience.

V & Z answer: That was the last piece of the night, and (Z) didn't have time to nuance it as much as he wanted. Then, when (V) read it over, he added the EXXON example. (Z) thought that did the job better, and so eventually went back and deleted the Pinto and Nova examples.

The Pinto example was correct; that absolutely does mean "penis" or "small penis" in Portugese. And Ford did change the name of that line in Brazil (they folded it into the existing line of Ford Corcels). The Nova example is more complicated; the name didn't actually interfere with sales at the beginning, since "Nova" would be pidgin Spanish. However, the car wasn't great, and the name lent itself to jokes about its less-than-stellar quality, as happened with the Volkswagen Thing, the AMC Gremlin, and the Suzuki Esteem in English. That did not help sales, and so contributed to Chevy's decision to wind production down.

S.S-L. in Norman, OK, asks: I'm trying to expand my horizons. Can you list for us what your favorite movies are, either for pure entertainment or for something deeper?

V & Z answer: (Z) is much more a movie watcher than (V) is, so for now, we will give you (Z)'s 12 favorite movies of all time. Next week, we'll return with a second list of "A dozen movies everyone should see." Here's the first list:

- The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

- Star Wars, Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983)

- M*A*S*H (1970)

- Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)

- The Godfather (1972)

- Back to the Future (1985)

- Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

- National Lampoon's Animal House (1978)

- To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

- 12 Angry Men (1957)

- The Blues Brothers (1980)

Hopefully one item on the list, at very least, piques your interest.

Previous | Next

Back to the main page