Previous | Next

New polls:

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Saturday Q&A

Heavy on COVID-19 and history, light on civics and politics, and only a few questions about the fellow who owns Mar-a-Lago.

Q: You wrote that "A recent report from the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) reveals that nearly two-thirds of false information comes from just 12 people." Who are those 12 people and what is known about their own personal vaccination status? M.R., New Brighton, MN

A: We will answer your question, but we are going to avoid links and specific names of books, websites, etc., because we don't want to give these people any assistance when it comes to search engines.

- Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. is the best-known member of the "disinformation dozen," and has

gained much notoriety from (1) his famous name, and (2) his propensity for anti-scientific thinking. He founded and runs

an organization dedicated to fighting childhood vaccines, and he has also written a book that reveals "the truth" about

COVID-19.

- Ty and Charlene Bollinger have made millions selling a 10-part anti-vaxx "documentary"

series. If you'd like a copy, it can be yours for the bargain price of $499. They are closely aligned with Kennedy, and

sell many copies of their documentary through his affiliated groups.

- Rashid Buttar is an osteopathic physician who is known for his conspiratorial and

anti-vaxx rhetoric. He claims to be able to cure a wide variety of ailments, including COVID-19, through chelation

therapy (removal of heavy metals from the body through chemical agents). He also sells copies of the Bollingers' video

series in exchange for a generous commission.

- Joseph Mercola is an osteopathic physician who also owns and operates an online store

where you can buy his many "alternative medicine" books, as well as—surprise!—supplements that will help you

to combat COVID-19.

- Erin Elizabeth Finn has been trying to find an Internet shortcut to wealth for a number of

years. Originally, it was a website built on the notion that she is attractive, but also geeky, and so you should really

want to see lurid photographs of her. Now it's a site doling out made-up health advice. On her site, she

enthusiastically endorses and sells Mercola's books and other products. She conveniently neglects to mention that they

are married.

- Sherri Tenpenny is an osteopathic physician who has written one overtly anti-vaxx book,

and three others where vaccine criticism constitutes a portion of the text. She claims the COVID-19 vaccine renders men

infertile, and also says that once the vaccination is complete, the government will be able to control people through 5G

cellular towers. She teaches a class about the evils of vaccines; it's a mere $600 for six lessons. That's just $100 a

lesson!

- Rizza Islam is a member of the Nation of Islam, and aspires to be the successor to Louis

Farrakhan. Mr. Islam is known for his homophobia, his antisemitism, his conspiratorial thinking, and his anti-vaxx rhetoric.

Incidentally, the official Nation of Islam Twitter account was

suspended

yesterday for spreading falsehoods about vaccines.

- Sayer Ji runs a website dedicated to information about alternative medicine and folk

cures. If you would like access, you can get it for just $850 per year (though you are also allowed to donate additional

funds on top of that, if you wish). He also sells his book and his newsletter.

- Kelly Brogan calls herself a "holistic psychiatrist." She sells several books that she has

written, as well as $400/year memberships to her website. She receives a commission for selling Joseph Mercola's

products, and is also an enthusiastic endorser of Sayer Ji's website and publications. Like Finn, she conveniently

neglects to mention that she and Ji are romantic partners who, while not married, do have two children together.

- Christiane Northrup is an OB/GYN who has written bestselling alternative medicine books,

has an online store selling supplements and quack cures, and who regularly appears on TV shows of dubious quality, like

"The Dr. Oz Show." Her theory is that the COVID-19 vaccine, by implanting people with microchips, will allow their minds

to be controlled via...cryptocurrency. Really.

- Ben Tapper is a chiropractor who owns a large and lucrative chiropractic practice, and who

also sells various products through his brick and mortar storefront. He says that he can use chiropractic medicine in order

to unlock the Lord's healing power. Who knew that the Lord needed the help?

- Kevin Jenkins is an osteopathic physician who runs an anti-vaxx nonprofit that is built around the notion that vaccines are primarily designed to hurt Black people. You might call it Critical Vaxx Theory. He is happy to take your generous donations in order to continue his "important" work. Like so many others on the list, he hawks his own product line, as well as the products of other anti-vaxxers.

In short, there are several themes here: (1) dubious branches of medicine, (2) gaining attention/influence, (3) grift, (4) grift, and (5) grift.

As to their vaccination status, none of them would publicly admit to having the COVID-19 vaccine, as that would undermine the foundation of their grift. However, it is likely that some of them have gotten the shot. Tapper, for example, claims to see dozens of patients a day without a mask; that would be rather problematic in terms of risk to himself and also risk of legal exposure if he wasn't vaccinated.

Q: Why do you think the Biden Administration hasn't been more aggressive in fighting COVID-19

vaccine misinformation and disinformation? This is probably the issue where I am the most disappointed with

the President so far. I

wrote to you

in Spring 2020, predicting the country would struggle to get past the pandemic without social unrest and unnecessary

loss of life because so many Americans are science deniers and they would refuse medical treatments. Vaccine

misinformation and disinformation have proliferated in social media websites and conservative media outlets in 2021.

It is one thing to try to deny science denialists attention, but it is another thing to let them push incorrect

information unchallenged. Anti-vaxxers are already getting attention from various media outlets so that ship sailed

long ago. If I were in the Biden Administration I would put medical personnel on Fox News, Newsmax, and other

conservative media outlets on a daily basis to refute anti-vaxx talking points. I do not support government censorship

of media outlets but it is borderline negligent for the White House to let so much misinformation be spread without any

attempt at rebuttal.

I have seen the effects of this in my own family. I have a college-educated brother who is refusing to get vaccinated

and has persuaded his son not to get vaccinated either. My brother, who uses tobacco and e-cigarettes habitually, won't

get vaccinated because YouTubers and talk radio hosts tell him the COVID-19 vaccinations available in the United States

are too risky. Apparently, using a legal and effective medical treatment his doctor recommends is "too dangerous" but

inhaling the fumes from burning poisonous plants on a daily basis is perfectly acceptable. He seems to think the

opinions of YouTubers should carry more weight than those of Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has over 50 years of medical

experience. I do not think my brother is genuinely stupid; I think he is a victim of a slick and well-financed

misinformation campaign.

R.M.S., Lebanon, CT

A: We're going to have to dispute your premise here: We would say the Biden administration is doing everything it can.

As you observe, there are significant limitations to what the White House can actually do. It would be both illegal and politically disastrous for them to try to censor Internet content or television "news" coverage. Biden himself has spoken out forcefully against misinformation—as we wrote, we don't think the "Facebook is killing people" thing was actually a gaffe or a misstatement. Further, as you somewhat imply, the politicization of this issue means that if Biden himself (or Kamala Harris, or Pete Buttigieg, or any other "politician" in the administration) pushes too hard, it could actually drive people further in the anti-vaxx direction. And so, the White House is deploying the two people who are broadly (though certainly not universally) regarded as "non-political" and "expert," namely Fauci and Surgeon General Vivek Murthy. You might not see them, but those two are doing press conferences and television hits all the time. Here, for example, is Fauci's appearance on Fox yesterday.

Q: G.D. from Louisville asked for a short and effective response to get through to anti-vaxxers. Your answer quoted the risk levels of COVID itself and of the COVID vaccine. Can you please provide the source you used for determining those risk levels? Meanwhile, I loved your answer for how to get through to believers in "the Big Lie." A.D., Gaithersburg, MD

A: Note that we were just trying to pick quantities that could be easily comprehended, so as to capture the comparative risk. You'd actually have to drive considerably more than 100 miles to achieve a risk level equivalent to your odds of dying from COVID. But 11,234.2 miles doesn't roll off the tongue so easily.

In order to estimate the risk levels, we had to pull information from several sources. To start, the AP reports that 150 of the 18,000 American COVID-19 deaths in May were vaccinated.

Meanwhile, the CDC reports that people who get vaccinated sometimes experience complications, like anaphylaxis. Further, 6,207 people have gotten the vaccine and died soon after. That's 886 per month. But many of those folks succumbed of something else, and their demise just happened to come in close proximity to being vaccinated. At most—and this is an upper limit—10% of the deaths were due to the vaccine, according to CDC analysis. Working with that, it means that, at most, about 87 people died in May from the vaccine. So, you have 237 people who got the vaccine and ended up dead, and 17,850 who didn't get the vaccine and ended up dead. That means that you're at least 75 times more likely to die due to COVID if you're unvaccinated.

Moving on to the traffic angle, a blood alcohol content (BAC) of .08 ("impaired") is enough to get busted for DUI in most places, but .20 is generally considered to be "drunk" (as in, too incapacitated to function), and most drunk driving accidents involve drivers in the .20 to .30 range. The NHTSA says that driving with a BAC of .20 makes you about 22 times more likely to be involved in a fatal accident than sober, and it just goes up from there, to about 35 times more likely at .30. We chose 25 times more likely as a fairly reasonable middle point. Meanwhile, the NHTSA also says that night driving is three times more likely to produce a fatal accident than daytime driving. According to our back of the envelope math, that means that nighttime (x3) + drunk (x25) is 75 times more dangerous than daytime and sober, and so roughly equivalent to unvaccinated vs. vaccinated. This was not meant to be a rigorous projection, just a reasonable ballpark figure.

Q: You

wrote:

"The Tampa Bay Buccaneers were an underdog heading into this year's Super Bowl. However, they are members of the

National Football Conference, also known as 'The Conference of Champions (and the Detroit Lions).'"

This means that you consider the NFC The Conference of Champions for winning 28 Super Bowls out of 55 (meaning that the

AFC won 27). Since you consider a 1.8 percent margin such a big deal, would you also consider it reasonable for our

previous president to have framed the 2020 election as a "landslide"?

S.Z., New Haven, CT

A: The NFL did not begin with the Super Bowl era. Franchises that compete in the NFC have 62 championships as compared to 33 for AFC franchises, and 6 for franchises that no longer exist. That means the NFC has 65% of "existing teams" championships and 61% of all championships. That's quite dominant. Admittedly, that also includes four for the Lions, with the last of those coming in 1957, so we really should have written "The Conference of Champions (and the Minnesota Vikings)." Either way, the qualifier is an NFC North team that cannot hope to capture the power and the glory of the Green Bay Packers.

As to electoral landslides, Donald Trump's claims have nothing to do with actual numbers, and everything to do with peddling the notion that there were vast numbers of fraudulent votes. As in, "We will prove that there were millions of fake votes, and that I, Donald Trump, actually won in a landslide."

Now, if the question is: "Was Joe Biden's win a landslide?," we would say that it is, at very least, landslide-adjacent. He won by 4.4% of the vote and more than 7 million votes. That puts Biden's win in the Top 10 by popular vote margin (though middle of the pack by percentage margin). More importantly, the partisan divide is so baked in right now that Biden/Harris won just about every vote they could possibly have won. The Electoral College, plus the focus on the vote margin in the three or four closest states, makes the contest seem closer than it really was.

Q: Given that the 2024 Primaries are less than 2.5 years away, what is the latest date that President Biden and former president Trump have to decide if they will run for re-election? R.H., Ottawa, Edmonton, Canada

A: We will begin by noting that the calendar for the 2024 election has not been set, and there is some jockeying going on over which states will hold their primaries/caucuses first. And with that said, we're actually going to give you three answers; you can decide which one best fits your meaning:

- The Pragmatic Answer: As a practical matter, Trump and Biden need to fish or cut bait by

the middle of 2023. If they're running, they need to get their campaign team in place and their fundraising operating at

full blast. If they're not running, they need to give their would-be successors time to do the same.

- The Technical Answer: As noted, specific deadlines for 2024 are not set, since even the

primary and caucus dates/order haven't been set. However, here are the dates for major-party

primary ballot access from 2020. Surely, the 2024 deadlines will be similar. And if you look at the link, you will see

the deadlines start to come up in November and December of the year prior to the election. So, if Biden or Trump want to

be on all or most of the ballots, they have to get in the race by late 2023.

- The Crazy Answer: Keeping in mind that the parties are not required to have primaries, and that they can just award delegates by fiat, it is plausible that Biden or Trump could allow the race to unfold without them, wait for the first wave of primaries and caucuses to take place and then make a declaration in late February or March 2024 along the lines of "Clearly, no candidate is having success in unifying the party, and so I'm going to have to run again." We actually doubt the Democrats would be willing to award Biden delegates by fiat, but it's possible. On the other hand, we already know the Republicans are willing to award Trump delegates by fiat. So, The Donald could probably hold out for a fair bit longer than Biden could. Heck, it's not impossible that Trump could declare a couple of days before the RNC (July or August 2024), and that the delegates would give him the nod over the person who actually earned it.

Q: I've lost track. Have you had your Trump-free week yet? (If no, how many Trump-free days have you had so far?) M.M., Sheffield, England, UK

A: We've only had about half a dozen Trump-free days, and no Trump-free weeks. Given Trump's likely impact on the 2022 Senate and House races, don't expect too many of them.

If you examine the list of recent stories that appears at the bottom of this page, you will notice that roughly eight of 50 are entirely or substantially about Trump himself:

- Jul23 Prominent Right-Wingers Are All Over the Place on Vaccination

- Jul23 Grifters Gotta Grift, Part I: The King of Grift...

- Jul22 Who Is Running the Trump Organization?

- Jul21 Trump Ally Arrested

- Jul19 AP Investigation: Almost No Voter Fraud in Arizona

- Jul19 Jesus and John Wayne

- Jul16 What Do Republicans Believe? (Capitalism Edition)

- Jul16 McCarthy Heads to Bedminster

The problem is that Trump has become, in most ways, the dominant issue in Republican politics. Even more important than one's position on abortion, or guns, or taxes is one's position on Trump, and whether or not he won the election. And so, it's virtually impossible to discuss any issue involving Republican candidates, or political maneuvering, without mentioning The Donald's name (even if he himself isn't really being mentioned). Further, there's no great name for the (large) faction of Republicans that follow the Dear Leader, besides "Trumpublicans," or "Trumpers," or "Trumpeters," or the like. So again, his name shows up a lot, even if he technically does not.

Q: I am writing because, when announcing the switch to the 2022 Senate map on July 19, you commented: "By popular request, we are switching into Senate mode today. Apparently, many of our loyal readers know what the 2020 presidential candidates look like and don't need to be reminded every day." I was one of those readers, and in fact, following your helpful tip, I blocked that element on your webpage months ago because I didn't want to look at Drumpf's orange face every day. Now that you've removed it, though, there's no reason to keep that element blocked, and indeed it would now be nice to be able to see what replaced it. That brings me to the question: How can one unblock an element on a webpage that was previously blocked? (If it's relevant, my browser is Google Chrome.) I am asking you because, since you posted the instructions on your website, there might be many readers in the same predicament. G.B., Buffalo, NY

A: This actually shouldn't be an issue, since the new image (the elephant icon) has a different name from the old image (the Trump mugshot). If you're not seeing the elephant, let us know, and we'll run instructions next week.

Q: As the gridlock in the Senate deepens, is it possible that the Democrats' political strategy for the 2022 elections is to put Republicans on record opposing issues that the majority of Americans support? I imagine short, single-issue, bare-bones proposals such as "authorize the existing DACA process" or "fund the IRS to find tax cheaters." Let it be known the bills will be managed to oppose all amendments. In expectation of a filibuster, couldn't Democrats immediately call for a cloture vote to put Republicans on record? This might be viewed as a "nuclear option" by those who dream of bipartisan politics, but it would be nice to see politicians squirm when they oppose popular actions. J.M., Downey, CA

A: It's not only a possibility, it's a certainty. The Democrats would prefer to run primarily on the things they've accomplished. But they are certainly going to hit the Republicans over the head with the things the GOP members have voted against. Further, the fewer things the Democrats get passed, the more hitting over the head they will do. You can already predict the commercials:

[grim, deep-voiced narrator who sounds like James Earl Jones]:

"Representative [fill-in name] voted against raising the minimum wage."

"He/she also voted against investigating the people who invaded the Capitol on January 6, 2021."

"And against childcare for working mothers."

"And against funding for our badly crumbling roads and bridges."

"And against giving the IRS resources to enforce the laws, so everyone pays their fair share."

"But you know what he/she voted for? Overturning the presidential election and awarding it to Donald Trump."

"Is this who you want representing you?"

Q: You wrote that "[Speaker Nancy] Pelosi [D-CA] can only appoint current members of Congress to actual seats on the [1/6] Committee." This begs the question, could she appoint any senators? Senators are members of Congress. Say, Mitt Romney (R-UT), Ben Sasse (R-NE), Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), or Susan Collins (R-ME)? Could add some heft to the proceedings, and be win-win for everyone involved. Bipartisan and bicameral too. T.K., Vashon Island, WA

A: We should have been more precise in our language. The rules of the House, specifically Rule X, Sec. 10, make clear that only current members of the House may serve on House committees.

Q: Should Republicans very narrowly take control of the house in 2022, and Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY) retains her seat, is it plausible Democrats and several Republicans could select her as the new Speaker? A.M., Eagle Creek, OR

A: It's not impossible, but it's not very plausible, either.

From the Democrats' point of view, Cheney is "right" on Donald Trump, but is otherwise a conventional neocon Republican, which means they don't agree with her on much of anything beyond Trump. They don't particularly want to give her whatever credibility would come with their support.

From the Republicans' point of view, meanwhile, this would be a stunt that would throw a giant wrench into their conference and into the operations of the House as a whole. Any GOP member who supported it would make themselves into an instant pariah within the Party, and would probably lose their seat at the next election. Meanwhile, the other Republicans would rebel against her at every turn, with Donald Trump egging them on all the while.

Since the Democrats don't agree with Cheney, and 95% of Republicans would resist her, she'd have a power base of something like 10 members. That's no way for a Speaker to get things done, and it's unlikely that Cheney would consent to trying it.

Q: Why is it a bad idea for the U.S. to split up into two countries? Americans have become two tribes that

stand against most everything the other side believes in. It seems like most states are solid red or

solid blue.

I don't know if this would be the best idea, but I think it should be considered. At some point, we have to make an

adjustment if things are not working.

B.S.M., Reykjavik, Iceland

A: As with R.M.S. in Lebanon above, we are going to have to dispute your premise.

What made the Civil War possible was that the pro-slavery Americans were overwhelmingly concentrated in roughly a dozen states. It is not a coincidence that the seven most slave-dependent states left after Abraham Lincoln was elected, the next four on the list left after Fort Sumter, and the remaining states with slaves (fairly small numbers of them) never left.

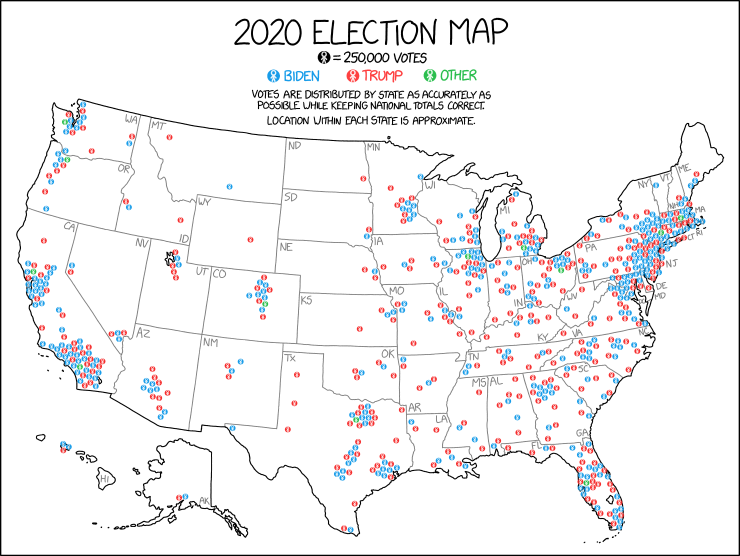

The use of red state/blue state terminology today, and the maps we see during and after presidential elections, may give the impression that the country is just as geographically divided as it was back in 186-61, but it's just not so. Take a look at this excellent map that XKCD put together:

Randall Munroe, who runs that site and who created that map, also offered this observation: "There are more Trump voters in California than Texas, more Biden voters in Texas than New York, more Trump voters in New York than Ohio, more Biden voters in Ohio than Massachusetts, more Trump voters in Massachusetts than Mississippi, and more Biden voters in Mississippi than Vermont.

In short, some sort of secession makes no sense under current circumstances, no matter how divided the two parties are, and no matter how "red" or "blue" some regions seem to be.

Q: All this talk about George W. Bush's reaction to the Afghanistan withdrawal had me thinking about another

question from the Bush era that I've never understood the answer to. Everyone has agreed, pretty much since it happened,

that Bush lied about the weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in Iraq. The manner in which the lie was constructed at many levels

of government, with complicity from the media and from partisans in Iraq, is well documented.

But why? If it wasn't WMDs, then what was the actual reason that will be listed in the history books?

J.H., Boston, MA

A: As chance would have it, (Z) already teaches the Iraq War, connecting it with one of the leitmotifs of his U.S. history survey class, namely "reasons Americans go to war." The basic argument is that because the U.S. is a democracy, a war needs to have broad support among the populace. And because the American populace is ideologically diverse, no one "reason" for war can do the job by itself. So, we tend to see the same justifications for war over and over, including in the case of Iraq. Here are the four biggies, all of which had a part in the Bush administration's thinking about the invasion:

- Money: Nearly all wars have some sort of financial motivation; sometimes the politicians

are honest about that, and sometimes they are not. The Spanish-American War, for example, was fought in part to maintain

access to Cuban sugar and tobacco. World War II was fought, in part, because a war-torn Europe (particularly a war-torn

UK) meant fewer purchasers for American exports. In the case of Iraq, the economic motive was oil; some members of the

Bush Administration were petroleum fanatics who once worked for Halliburton (Hint: Ickday Eneychey), and wanted to

expand access to Iraqi reserves.

- National Security: Every war since 1898 has been sold, in part, on the assertion that

fighting the war would make America safer. The Cold War wars (Korea and Vietnam) are obvious examples, but this was also

the case with World War I and II, when the Germans were presented (with some reason) as an existential threat to

America. You might possibly be wondering how much of a threat Spain really was to the United States in 1898, and the

answer is that they weren't; the national security argument in that case was called

"Mahanism,"

which boiled down to "we need islands around the world for use as coaling stations, and if we take Spain's remaining

territorial possessions—Guam, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, etc.—then we will have them, and we'll have a

powerful two-ocean navy that can keep America safe." In the case of Iraq, there were no WMDs, but Bush & Co. believed that

toppling Saddam Hussein would strike a blow against terrorism, and would also allow the U.S. to build a democracy in

that country, which would serve as a model for/influence on other Middle Eastern nations.

- America to the Rescue: There are few people who are not inspired by the thought of helping

to save those who are weak, oppressed, exploited, less fortunate, etc. And so, there's always a victim of some sort that

Superman...er, the U.S. is proposing to rescue. In some wars, you can surely guess who it was—Cubans in 1898,

South Koreans in 1951, Vietnamese folks in 1964, etc. For other wars, you might be surprised. World War I, for example,

was sold based on the notion that the U.S. owed a debt to the French (dating back to the Revolutionary War), and that

this was a chance to repay that debt. In World War II, the people who most needed rescuing were the Jews

and the other victims of the Nazi death camps, but antisemitism being rather widespread, Franklin Roosevelt instead

focused on rescuing the Brits and the Chinese. Anyhow, the Iraq War is one of the ones in the "obvious" category;

the Bush administration declared (and some members really believed) that the U.S. was freeing the poor Iraqi

people (particularly the Kurds) from the oppressive rule of Saddam Hussein.

- Fight Evil: Similarly, everyone likes to think of themselves as the good guys/gals,

doing their part to rid the world of unmitigated evil. In some cases, the would-be opponent was pretty much the

textbook definition of evil, and so this case wasn't too hard to make. Adolf Hitler is the obvious example, of

course. In most other cases, things were a little fuzzier, and it was up to the government and the hawkish types to

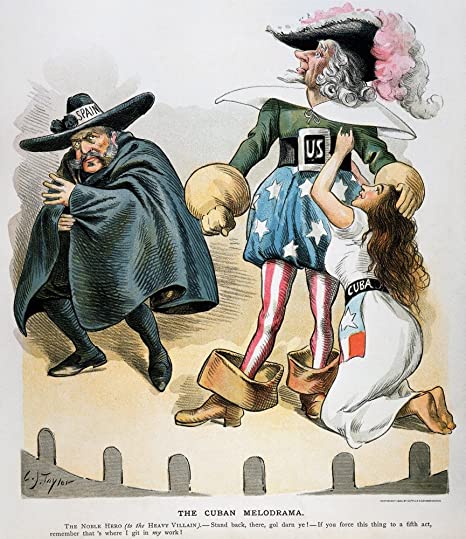

eliminate any ambiguity and to turn the enemy into something almost cartoonish. For example, here is an image that

(Z) shows during his lecture on the Spanish-American War:

The same happened with the Kaiser in World War I, the Kim family in the Korean War (and ever since the Korean War), and Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam (not to mention every Soviet premier except for Mikhail Gorbachev). In the case of Iraq, the evil was terrorism broadly, Islam subtextually, and Saddam Hussein/his family/his cronies specifically. Recall the Iraqi Most Wanted playing cards that were handed out to soldiers and that were sold in the U.S.

Now, these persuasive arguments are generally necessary, but not by themselves sufficient. Once public sentiment has shifted in the general direction of approving a war, Americans still need to feel they are acting in self-defense, and that they are not aggressors. So there is always an "attack" of some sort on the U.S. that finishes the deal, and causes the U.S. to enter a war. We put "attack" in quotes because while sometimes the attack is real, other times it's exaggerated and/or manufactured. Anyhow, the incidents that did the job for the major wars of the last 125 years are, in order, the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine (Spanish-American War), the Zimmermann Telegram (World War I), Pearl Harbor (World War II), the communists' invasion of South Korea (Korean War), and the Gulf of Tonkin incident (Vietnam). Bush & Co. knew there was zero chance of Iraq actually attacking the U.S., so they adapted 9/11 for the purpose, despite Iraq's non-involvement with that incident.

Anyhow, that is how it's being taught right now, at least in one classroom. And (Z) thinks this gives a pretty good sense of how it will be seen in future classrooms/books, albeit possibly with a bit less detail. (Z) also frames this as part of a new age of American imperialism, similar in some ways to the original, and different in other ways. That framing is also a likely possibility in the history courses/history books of the future.

Q: My partner and I are wondering if you could give us your opinions about the situation in Cuba, both currently and historically. The mainstream media seems to be united in presenting the protesters there as representing the majority of the Cuban people in a noble quest for freedom against an oppressive government. However, the left-leaning media points out that U.S. sanctions have played a large part in creating the economic hardships which are being protested, and that Cuba under Castro made great economic/social strides, despite U.S. interference—as evidenced by their high literacy rate, representation of women in politics, universal healthcare system, etc. I'm disinclined to trust U.S. mainstream representations of the situation in Latin American countries, because of the long history of U.S. manipulation/intervention/propaganda around these issues, but I don't know a great deal about Cuba. What is your take on the situation? A.W., Northglenn, CO

A: Sometimes, sanctions work. Sometimes, they don't. And the textbook case of sanctions not working is...Cuba. In that case, all the sanctions have done is cause suffering among the people, with the successive Castro regimes (Fidel and Raúl, not Julián and Joaquin) easily able to foist the blame off on the evil Americans. However, because anti-Castro sentiment became a huge issue among Cuban-American voters in the United States, and because they are a key constituency in the swing state of Florida, no president has been able to back off those sanctions. Barack Obama tried, and he and his party took a beating in Florida as a result. The Democrats have not won a Senate seat there, nor a gubernatorial election, nor the state's electoral votes, since Obama announced in late 2014 that relations would begin to be normalized (a decision later reversed by Donald Trump).

It is also no secret that, in addition to the sanctions, the U.S. has mucked around in Cuban affairs a lot, from basically creating the island's original post-Spanish government to the Bay of Pigs. This interference has not helped the Cuban people. The presence of a major military base on the island, namely Guantanamo Bay (which was essentially a "thanks for helping us win independence" gift in 1899) has not been great for relations either.

That said, communism has proven over and over to be a not-viable form of government and economy. And the Castros had both autocratic and corrupt tendencies and, like many communist leaders/dictators, worried more about themselves and their inner circle than the people over which they ruled. That may not have been true back in 1959, during the revolution, but as they say, power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

If you examine the Human Development Index, a United Nations Development Programme measurement that takes into consideration the average citizen's health, level of education, and income, you'll see that Cuba comes in at #70, a fairly middling ranking that puts them in the same neighborhood as Iran, Mexico, and Ukraine, and ahead of Jamaica, the Philippines, and South Africa, but well behind Argentina, Greece, and Saudi Arabia (the U.S. is #17, for those who don't want to click on the link, and the #1 country is Norway). Undoubtedly, the United States deserves some of the blame for Cuba's less-than-stellar state of affairs, but so too does the leadership of the Castros.

Q: Politically speaking, what was the most forgettable decade (or other ten-year span) in U.S. history? E.W., Skaneateles, NY

A: Assuming we exclude the colonial era, then the answer is surely 1815-25, the so-called "Era of Good Feelings." There was effectively only one political party (the Democratic-Republicans), the presidents of that time favored a small and passive federal government, there were no foreign wars, and relations with the Natives were relatively peaceful.

If we had been doing Electoral-Vote back then, we would have had a lot of trouble coming up with enough content for each day's broadside before it was posted in the public square for all to read.

Q: What were the goals of the Whig Party, and what were the major disagreements between the Whigs and the Democrats? And did the Whig Party achieve anything meaningful? F.S., Cologne, Germany

A: The problem with the Whig Party is that their only common goal was to oppose; first Andrew Jackson and then Jackson's political and spiritual successors. They particularly disliked Jackson's anti-bank stance, his aggressive exercise of presidential powers, and his inclusion of working-class and immigrant voters in his party.

Beyond that, the Whigs did not agree on an awful lot, and "We don't like Jacksonian Democracy" is not a great plan for winning elections or for governing. To the extent that they had an identifiable policy plank, it was support for roads, bridges, and other internal improvements with an eye toward developing the nation's manufacturing economy. Southern Whigs weren't entirely on board with this, but Northern Whigs helped lay the groundwork for the construction and operation of America's first factories. It was also Whiggish folks who got the Cumberland Road built, although that project was mostly undertaken before the Party had formally organized.

If you really want to get into the nitty-gritty, Daniel Walker Howe's The Political Culture of the American Whigs is still the definitive book on this subject, even though it's now more than 40 years old.

Q: D.C. in Rabun County asked about the reputations of U.S. presidents, noting that Ulysses S. Grant's reputation was degraded after the Civil War by "Lost Cause" propagandists. As the conquerors usually write history (or so it is said) how did they succeed in defaming Grant's reputation? J.S., Durham, NC

A: At risk of being immodest, there are perhaps a dozen people who would really be able to knock this question out of the park. One of those is (Z), and two of the others were on his dissertation committee. This is offered not as braggadocio, but as warning that you're about to be exposed to some inside baseball. Hopefully it all make sense.

To start, you are right that the old cliché tells us "the victors write the history." However, anyone who says that is revealing that they haven't actually studied much history. Quite often, the winners have no need to write the history since they won. The losers, meanwhile, generally have a need to soothe their psychic wounds, and perhaps to justify (or erase) bad behavior that took place before and/or during the war. The Confederates and their Lost Cause mythology are a famous example of this, while the Turks and World War I ("What Armenian genocide?") are another.

While Grant was alive, he was too famous and too popular to be successfully torn down. His funeral was one of the best-attended in world history, and was the preeminent news story of that year (1885) and really of that decade. It wasn't until after his passing that the Lost Cause mythology, and eventually the anti-Grant interpretation, took hold outside the South.

So, how did it happen? Well, at this point we will note that the two biggest historical reenactment movements in the U.S. are Civil War reenactment (i.e., the subject of Z's dissertation) and Renaissance Faire reenactment. These two communities emerged at the same time (the 1960s), albeit on opposite coasts. That is not terribly surprising, because the 1960s were a tough decade for America. And when "the present" is rocky, it's sometimes nice to escape to "the past," even if that past is being viewed through strongly rose-colored glasses.

But why, you may ask, were those the past periods that people gravitated towards? This is actually pretty important to your question. Anyone who has any experience with Renaissance Faire reenactment knows that it's really more like medieval reenactment. And the medieval era was about as far removed from modern society as is possible: low-technology vs. high-technology, farming vs. industry, rigid social structures vs. social mobility, clearly defined gender roles vs. more fluid gender roles, chivalry vs. (frequent) incivility. In other words, when people look back to an idealized past, they tend to pick one that is as far removed from the present as is possible.

So, why the Confederacy, then? Well, they regarded themselves as a latter-day medieval society. They had a feudal system, over-the-top chivalry, strictly defined gender roles, limited technology, etc. Antebellum Southerners, at least the ones with money, put suits of armor in their houses, created family crests, and often posed for paintings that presented them in the costume of medieval knights. And among nearly all white antebellum Southerners, the most popular literature was medieval romances, like the books of Sir Walter Scott.

In other words, when things got tough in the 1960s, some folks turned back to Europe's last medieval era, and others turned back to the United States' last medieval era (or "medieval" era). And that is the same process that took place outside the South between the death of U.S. Grant and, roughly, World War II. The industrial North and Midwest, and later the far West, had become challenging places thanks to immigration, crime, overpopulation, social strife, and a host of other changes. Sometimes, people wanted an escape, even if it was temporary and even if it was only in their imagination. And so, they were a ready audience for the idealized, moonlight and magnolias vision of the antebellum South that the Lost Cause writers were peddling.

The absolute height of the Lost Cause as a national phenomenon (outside of Black Americans, some academics, and some political liberals, of course) was surely the 1939 release of the movie "Gone with the Wind." And those who have seen it may recall the crawl that appears onscreen at the start of the movie:

There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South.

Here in this pretty world, Gallantry took its last bow.

Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave.

Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered, a Civilization gone with the wind..."

Note that Lost Cause thinking survived beyond 1939. This is part of what made the rise of Civil War reenactment possible in the 1960s. And it lingers even today. However, it lost its hold on many people after World War II, in part because that experience taught many folks that there is no such thing as a noble war, and in part because Black folks successfully began to challenge the stereotypes that the Lost Cause was founded upon. It is instructive that the 1946 Disney film "Song of the South," which was basically Walt's attempt to make his own "Gone with the Wind," was among his biggest failures, and was widely criticized for being offensive, racist, too romanticized, etc.

So, there you have it. And because there was so much inside baseball here, we'll concluded with an executive summary: Grant lost favor with many Americans because he (appropriately) fought a brutal, industrial war and so served as a reminder of some of the brutal aspects of the 1890s-1940s, while Robert E. Lee (seemingly) fought a gallant, chivalric, civilized war, and so served as a nostalgic reminder of what had supposedly been "lost."

Q: Politicians blinded by corruption and power is nothing new. However, as we just learned again,

Donald Trump must have read "Dictatorship for Dummies" since so much of what he did followed the same basic blueprint

dictators and would-be dictators have historically used. I think most would agree he would have embraced dictatorship

if things went according to plan.

Other than Trump, has there ever been a president or other powerful U.S. politician with such obvious dictatorial

aspirations? Are you concerned any of the contenders for the "Trump lane" have similar aspirations? (Other than

"Pinky and the Brain," of course.)

S.S., West Hollywood, CA

A: Without question, the two most dictatorial presidents in U.S. history before Trump were Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Both of them aggressively stretched the Constitution in various ways (suspending the writ of habeas corpus, emancipating slaves, nationalizing portions of the economy, interning Japanese Americans, etc.). Both were attacked as aspiring dictators in their time. And since they both died in office, we cannot be 100% sure what they would have done had they reached the legal ends of their terms.

That said, one cannot seriously argue that Lincoln or Roosevelt actually had dictatorial aspirations. Yes, they were willing to assert the powers of the presidency in a way that no president had before, but they felt justified in doing so by the circumstances of the Civil War, the Great Depression, and World War II, all of which can be fairly described as existential crises for the United States. Many Americans of their respective eras agreed with their decisions, and many historians have been understanding, if not supportive, since.

Beyond that, Lincoln insisted on holding the election of 1864 even when he had support for postponing or canceling that contest. And although he had rolled up his sleeves and was ready to get to work on Reconstruction when he was killed, he had also begun planning for his retirement (he wanted to travel to Europe and the Middle East). Similarly, FDR nearly stood down at the end of his second term, and only ran for a third term because World War II was clearly imminent. And although he likely did not expect to survive his fourth term, he too had begun thinking about retirement, and looked forward to the possibility of taking up permanent residence at his spa in Warm Springs, GA. That's where he was when he died, incidentally, as he tried to recover from his trip to Yalta.

As to non-presidents, the only real contender is VP Aaron Burr, who allegedly planned to form a country from Texas, parts of Mexico, and parts of the western U.S., and to install himself as dictator. However, there is no proof for this, and historians today believe this story was mostly or wholly an invention of his enemies.

And so, Trump is indeed the only American who can reasonably be deemed to have had dictatorial aspirations.

Q: Regarding the questions you have answered about textbooks, I remember reading that textbooks were actually read, edited and voted upon by the Texas government for many states beyond just Texas. Is this correct? Who decides what should be in history books for schools? Are they party affiliated? Is each state different? C.H., Sacramento, CA

A: This is a little tricky, and we will start by noting that the way things work are going to differ a bit depending on which state, county, school district, etc. we are talking about. In other words, this answer is generally correct, but it's not universally correct.

Anyhow, there is a fair bit of money to be made in selling textbooks. However, it also costs a fair bit of money to produce one. A publisher has to hire an author (usually, though not always, one or more professional historians). Then, the book has to be designed, and edited, and illustrations have to be secured, and an index and bibliography have to be compiled, and so forth. The cost, before the first copy of the book has actually rolled off the press, can easily run into six figures.

Meanwhile, textbook-purchase decisions are usually made at the district level; the folks who run the district acquire copies of whatever textbooks look promising, read them over (ideally), and pick one. However, municipal and state authorities do tend to exert some influence over the process. In some states, there are laws on the books about specific things that must be taught, or that cannot be taught, and only books that adhere to those laws can therefore be considered. In addition, nearly all states have some sort of "standards" that give general guidelines on what they expect to be covered. Sometimes, states develop their own standards, and sometimes they adopt standards that have been developed by others (Common Core, for example, is basically just a set of curricular standards).

Turning back to the business side, a textbook publisher will only invest $50,000 or $100,000 or $200,000 in a textbook if they believe there is a sizable market for that book. Indeed, if a would-be author submits a proposal for a textbook (or a reference work, for that matter), the first thing they have to do is write up a market analysis and talk about how their project will fill some gap in the market. And one way to capture market share is to pick a big, wealthy state and to produce a book that adheres very closely to that state's laws/curricular standards. So, Texas can and does get textbooks that are perfectly tailored to the desires of school and government officials. California, too, and Florida, and New York, and Pennsylvania.

By contrast, states like Mississippi, Vermont, and North Dakota just aren't big enough markets for textbook publishers to bend over backwards for. So, what smaller Southern states will do is just pick a book that has been tailored to Texas' needs, figuring it will be close enough. That means that Texas is indeed influencing the textbooks being used (and thus the history being taught) in some other states, although not due to some sort of direct decree from the people in Texas. It's just a byproduct of how the publishing industry works.

Q: I'm curious as to what impact Texas HB 3979 (and similar legislative efforts there and in other states) will have on graduates of those states in seeking either higher education elsewhere or even employment? Both (V) and (Z) are professors at Universities. If a graduate from Texas applies at either of those institutions, would they receive extra scrutiny, or even prejudice, due to a clearly compromised education? Are employers going to look askance at graduates from Texas for positions where knowledge of subjects like race, American history, climatology, or even human sexuality are relevant? M.W., St. Paul, MN

A: We're not sure exactly what level of the educational system we're talking about here, so we'll run through several possibilities.

First of all, when it comes to admission to a university as an undergraduate, having been schooled in Texas is not really a problem. A university expects to educate students, regardless of how raw those students are as raw material. And since there is such wide variance between regions, and cities, and districts, and even specific schools, the goal is to identify the most appropriate candidates relative to similar candidates from the same area. In other words, Texas students are largely compared to other Texas students, not Washington students.

When it comes to admission to a university as a graduate, what matters is the undergraduate university, and how well the student did there (including any preparatory work they might have done in the field they expect to study). In this case, high school doesn't matter, and a graduate from the University of Texas would be on the same footing as one from the University or Oregon or the University of Illinois. It is possible that a graduate from a religion-forward, right-wing-politics forward school, like Bob Jones University or Liberty University, could be at a disadvantage, but that's not what you asked.

When it comes to hiring as a faculty member, what matters is the quality of the work the person did as a graduate student (including publications) and the reputation of the university they attended. Here, attending anything other than an elite university can be a real problem for an aspiring faculty member. There are so many graduates to choose from that an enormous percentage of hires (85% or so) come from the Top 15 or so schools in whatever field it is. In history, for example, you can either be a graduate of one of those upper-tier schools (Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Brown, Penn, Chicago, Berkeley, Stanford, UCLA, Duke, and a few others), or you can go to a lower-ranked university but do work in that university's specialization (e.g., Native American history at the University of Oklahoma, Western U.S. history at the University of Colorado, Boulder), or you can hope you get really lucky. This is going to be the case for pretty much all faculty jobs, even at places like Northwestern South Dakota State Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical University and Barbers' College.

As to employers, we would guess that the problem with a Texas high school graduate isn't necessarily that their education is of poor quality, but that they only have a high school diploma. Just about any job where things like race, American history, climatology, human sexuality, etc. are going to be essential is going to require a university diploma. And once a person has a university diploma, then the considerations work about the same as they would for graduate school (e.g., how did they do in college, did they get any relevant experience, etc.).

Q: The AAPOR report on the 2020 polling debacle is out. They don't have an answer. There is a

list of issues that are not the problem, and only a guess as to what it could be: basically, Trump signaling to his

minions that polls are fake. From the executive summary: "Self-identified Republicans who choose to respond to polls

are more likely to support Democrats and those who choose not to respond to polls are more likely to support

Republicans."

My question is, what should you do now? By "you" I mean not just individual pollsters, but aggregators such as

yourself, Nate Silver, Sam Wang, since most of us consume polls via your websites. You could ignore the problem

assuming it is exclusive to Trump and will not be a factor in 2022 and beyond. Or one could try to correct for this

effect, but unless there is some orthogonal variable that can identify this crowd, there is not much you can do other

than increase the uncertainty bands. The executive summary made it clear " Polling error was not primarily caused by

incorrect assumptions about the composition of the electorate in terms of age, race, ethnicity, gender, or education

level."

A.L., Rutgers, NJ

A: Well, this site was once almost 100% polling driven, but it's not anymore. We've already produced over 1 million words this year with less than 5% of those being about polling.

As to our polling coverage and analysis, which obviously becomes more substantial as elections draw close, we are in no position to correct for the pollsters' errors. We don't have their raw data or the "secret sauce" of adjustments they applied to that raw data. Either they figure it out (which they probably will) or they don't. We will do what we do, which at very least will be interesting and will serve to identify shifts in momentum.

We would also point out that our main focus is the presidential race, and despite last year being "the worst polling year in a generation," we had either 47 or 48 states (plus D.C.) correct. Our numbers had Florida and North Carolina breaking slightly for Joe Biden (which was incorrect), and had Ohio as a toss-up. But our written text on Election Day said that we didn't really think Ohio was a tossup, and that it would go for Donald Trump. So, depending on whether or not you give us the Buckeye State, we had an accuracy rate of either 94% or 96%.

We don't know what other polling aggregators will do, but we would guess they adopt a similar outlook.

Q: Please, no more links to articles behind paywalls. K.M., Moore, OK

A: We do our best, which is why we rely a lot on CNN and Politico—their stuff is good quality and it's free.

However, sometimes it is necessary to link to paywall articles because those are the only ones that work. It could be that only The Washington Post has a particular poll, or that Sen. Bernie Sanders' (I-VT) op-ed appeared in The New York Times, or that only Slate wrote about the relationship between voting patterns and minimum wage. When we do this, we almost always (99.9% of the time) link to sites with soft paywalls (i.e., you get a certain number of free articles each month). This is why we almost never, for example, link to The Wall Street Journal; they have good content but a hard paywall.

The day you wrote in, the only "paywall" article we linked was from McClatchy DC. When you click on their articles, it looks like they have a hard paywall but, in fact, it's a soft paywall. You just have to sign up for a free account and you get a certain number of articles per month. It is also an open secret that sites that give you a certain number of free articles and then demand payment keep track of how many you have read using cookies. In most cases, if you clear all your cookies, your count of read articles is reset to zero and you get another five or six. This can be repeated forever.

Q: I notice that on Thursday you had the embarrassing

moment

where you had to note that the story about Nancy Pelosi rejecting two of House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy's (R-CA)

nominees was wrong, and that this "forced more than a few outlets to reword their coverage (we don't like to do that,

but we did add a very rare "update" note to our item). You also had to edit that day's post further, as

the item

on the special election in Ohio initially appeared to suggest that you thought the midterms were this November, as

opposed to next.

I ask this not to make fun of the mistake (if I wrote as many words as you do every week for publication, they would be

completely riddled with grammatical and factual errors), but because you've talked about your writing processes in some

of these Q&As and I'm interested in how often you need to correct things and when it's necessary to include notes

that the piece has been edited to correct an error, as opposed to just correcting the mistake and leaving it at

that?

T.J., Antwerp, Belgium

A: As Marshall McLuhan observed, "the medium is the message." What he meant by that, in essence, was that every medium of communications affords certain opportunities, and forces certain tradeoffs, and that is baked in regardless of the specific content. One thing about a site like this, which goes live literally minutes after we finish the day's posting, is that mistakes will be made, sometimes big ones. Another thing is that we can't always "show our work." That means that while we might base an assertion, or a paragraph, or an item on six different articles we read, we usually just link to the best one. Similarly, we try to qualify the assertions we make, but overdoing that can make the prose flabby and difficult to read. It is so out-of-character for Democratic members of the House to express such strong opinions on a touchy subject without Pelosi's say-so that the inference we (and others) made was a slam dunk. Of course, sometimes even slam dunks end in misses.

Anyhow, we make anywhere from a couple corrections, to a couple of dozen, each day. This includes grammar stuff, things that some readers found unclear, factual errors, formatting issues, and a bunch of other things. Sometimes a reader or one of our copy editors suggests an example that we overlooked, or that is better than the ones we used. Sometimes a reader or one of our copy editors comes up with a joke that we go back and add in.

We have experimented, in the past, with more aggressively identifying the things we've changed. But writing those up takes time, and time is already scarce. Further, the line between "what needs a note" and "what doesn't" can be really hard to draw. If we swap "insure" in for "ensure," because we mistyped (we definitely know the difference between those words), does that require a "correction"? What if we accidentally identify Liz Cheney as (R-WA)? Or if we identify someone as a psychologist when they are actually a psychiatrist? Or we write that Ronald Reagan ran for governor in 1964, when he actually ran in 1966? So, we just take the position that a few errors are inherent to the medium and that readers understand that.

That said, we do:

- Put the occasional note on really big missteps, like the Pelosi story.

- Refer back to things we might have messed up on previous days, and clarify them.

- Respond to nearly all e-mails sent to the corrections e-mail address, either confirming that an error was made and

was fixed, or else explaining why the point in question isn't actually an error.

- Run letters on Sundays from folks who are in a position to correct or clarify things we might have fumbled (e.g., "You were part right about how depositions work, but...")

Q: Why are you continuing to publish the comments from [X]? C.Z., Sacramento, CA

A: C.Z. asked about a specific individual, but there are a handful of regular contributors to the letters page that we get this basic question about. Often those messages are accompanied by supposition that the identity is actually a front for (V) or (Z), or that we're publishing the problematic letter for laughs, or—most commonly—that we deliberately pick letters that will aggravate people, stir the pot, generate clicks, etc.

None of these suppositions is correct. We do not adopt fake identities (other than V and Z, which are not a secret), and we don't pick letters because they will piss people off. The purpose of adding the mailbag was to sometimes move the site beyond our perspectives as two white, male academics who live fairly comfortable lives and have similar political outlooks. Much of our readership lives, to a greater or lesser extent, in that same bubble. So, when we believe a letter represents a real perspective that is out there, and we think some readers might like to know about it, we consider running that letter. That holds even if we disagree, or think the letter writer's assertions are trite, or full of holes, or self-involved, etc.

We often know that a particular letter will aggravate some readers. And what we say to ourselves when we run such a letter is that, if given the choice, it is better that the letters be annoying 5% of the time than that they be comfortable and unchallenging 100% of the time.

Previous | Next

Back to the main page