Previous | Next

New polls:

Dem pickups: (None)

GOP pickups: (None)

Saturday Q&A

Another day where some of our answers are not going to be universally beloved, if you know what we mean.

Current Events

D.E. in Lancaster, PA, asks: It was reported this week that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) said this in regards to the House 1/6 Committee: "It will be interesting to see what facts they find... We're all going to be watching it. It was a horrendous event... I think what they're seeking to find out is something the public needs to know."

When I read this, my face rivaled the shock/horrified look on Macaulay Culkin's face in Home Alone. Just what the hell happened to our beloved Minority Leader, who always puts power before country? Was he momentarily giddy from kicking a starving orphan puppy that he blurted out something so uncharacteristic? Did someone get three ghostly visitors at night? Has Mitch been replaced by a Pod Person? Did our Turtle get sucked into the multiverse, to be redeemed by his archnemesis Barack Obama, before being returned to ours? Do you guys have an explanation for Mitch's sudden turn that doesn't rely on genre plotlines?V & Z answer: Never say never, but we doubt McConnell has turned over a new leaf. He is very concerned about his own influence over the Republican Party, and a great many of the tools in his toolkit involve behaving in an underhanded or duplicitous manner. Our guess is that McConnell sees this 1/6 Committee as a real opportunity to badly wound Trump and his acolytes, and that hinting at his support for the investigation gives it credibility without triggering a full-frontal assault from the Tucker Carlsons of the world.

J.M. in San Jose, CA, asks: Pundits say the Republican strategy is to delay the 1/6 Committee as much as possible with the goal of taking the House in the 2022 elections, then shutting down the investigation. Is there any way the committee can prevent that? Maybe pass all the info they have to the Department of Justice and ask for a special investigator?

V & Z answer: We have no inside information, of course, and folks like Bennie Thompson (D-MS), Adam Schiff (D-CA), and Liz Cheney (R-WY) are too clever to show all the cards in their hands right now. However, we would guess that this is indeed their fail-safe plan. They gather as much information as they possibly can, and if it looks like the Committee is in imminent danger of being shut down, they dump the information on AG Merrick Garland and tell him it's now his to deal with. If the evidence that crimes were committed is strong enough (and, frankly, it looks to be strong enough even right now), then he will certainly pick up the ball and run with it. He's cautious, but he's also not willing to look the other way when it comes to enforcing the law (see Bannon, Steve).

S.K. in Sunnyvale, CA, asks: Of the FDA's making "permanent" its pandemic-era policy of allowing the remote prescription of abortifacient medicines, you wrote: "...if a new president tries to overturn an existing FDA policy, they have to have a clear justification for doing so." Flipping the script, what stops anti-choice AGs from suing right now over the Biden administration making the pandemic-era policy permanent? Does the Biden administration not also need a clear justification to continue the remote pill prescription policy post-pandemic?

V & Z answer: Actually, the initial change in policy was in response to a lawsuit filed by the ACLU. So, the Biden administration can point to that and say, "Hey, we're just doing what the courts told us to do."

It's true that the red-state AGs could try to file suit now, and get the ACLU decision overturned and the administration policy reversed. However, working against the red-state AGs, and in favor of the ACLU and the White House, is that the new rules have been in place for over a year, and the world has not come crashing down around us. So, any lawsuit would have to come up with a heck of a good explanation as to why the availability of the pill would be disastrous in 2022, 2023, etc. when it wasn't disastrous in 2021.

There's also one more issue, and it's a pragmatic one: There is a world of difference between enforcing a policy and not enforcing a policy. That is to say, the Supreme Court could hold a special session today and tell Joe Biden that he's out of line and that he has to change the rules back to the way they were before the pandemic. And the President could very well say, "Ok, no problem. Officially, women must once again get abortion pills from their doctors, in person. However, I have instructed the FDA and other relevant agencies not to enforce that rule." There is nothing SCOTUS would be able to do in response. By contrast, if a Republican president takes office and changes the rules after 4-5 years of mifepristone, etc. having been widely available, then that is a case of enforcement action replacing inaction. And that Republican president would have to come up with a great explanation for why the change is indicated, and why it's acceptable for the FBI or U.S. Marshals or whomever to start arresting pregnant women/pill providers.

E.W. in Skaneateles, NY, asks: I'm confused. In your item about abortion, you wrote "there are no states near Mississippi" where abortion remains legal. Isn't abortion still legal in all of the states next to Mississippi?

V & Z answer: It is true that abortion remains legal in all of the states bordering Mississippi, and in 49 of the 50 states (and DC), with Texas being the exception. It was not easy to write that item, and time was tight, but we meant it to be understood in future tense, as we laid out the back and forth that we would expect to take place in a post-Roe world. That is to say, if we get to a situation where abortifacient pills are the only option for pregnant Mississippians, then at that point it will be the case that there are no states that border Mississippi where abortion will be legal. To wit, Alabama, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana—Mississippi's four neighbors—all have "trigger" laws on the books that would impose a near-total ban on abortions as soon as federal law/jurisprudence makes that possible.

A.L. in Osaka, Japan, asks: I don't get it. Why is Joe Biden being so passive in the face of a COVID-19 surge? Why not move for an aggressive mask mandate, send out free test kits, fast track through executive orders the vaccine mandates lingering in the courts, and address the nation from the Oval Office. Is Biden going to end up looking like another Jimmy Carter?

V & Z answer: We think you might be assuming facts not in evidence. Let's take this item by item:

- Mask mandates: At this point, the cost/benefit analysis of mask mandates probably doesn't add up, at least not on a national level. Just about everyone who is going to wear a mask, either due to social pressure, or basic human decency, or fear of illness, or whatever, is already wearing one. The remainder have now been digging their heels in for over a year, and are all but certain to defy an order from the federal government, usually with approval from authorities in their state. There aren't enough U.S. Marshals or FBI agents or even active-duty troops to compel, say, non-cooperative Floridians to mask up if Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) refuses to be a partner (and there's no question how he feels about the subject).

Meanwhile, mask mandates generate all sorts of political blowback, and also resistance to other COVID-prevention measures, like vaccination. Better for the administration to choose one point of focus (the vaccines) than many. Further, there are some clear downsides to masking mandates, including hindering the social development of children and triggering depression in both children and adults.

The cost/benefit analysis may come out differently if we consider, say, very blue states with one or more large cities, where social pressure might be more effective, and where the risk of a truly severe outbreak is greater (because of tightly packed urban populations). However, that's a question for the governors and not for the president. Though you can bet Biden was on the phone with Gov. Kathy Hochul (D-NY) before she imposed that state's new mask mandate, and that he's been on the phone with Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) and others.

- Free test kits: The administration is working on this; they have already got everything in place for the 150 million Americans with private insurance to receive free testing kits at home. The White House hopes to extend that to Medicaid and Medicare recipients as soon as the funding is found. And Team Biden is also distributing 50 million free-of-charge test kits to designated community centers around the nation; those community centers generally serve poor/under-insured populations that do not live close to hospitals or other medical facilities.

- Vaccine mandates: The administration has three vaccine mandates that it's tried to implement, one for healthcare providers, one for federal employees (including those who work for federal contractors), and one for employees of large private business concerns. All three are tied up in court, though the administration just won its case over the large-employer mandate, leaving only one level of the court system to go (the Supreme Court, assuming they even agree to take the case). The President cannot issue new/more forcefully worded executive orders that say "Ah! Forget the courts!" If they could, imagine what Donald Trump would have done with that power.

- The bully pulpit: Every time that Biden has spoken publicly in the last couple of months, he's sounded the alarm, and reiterated how important vaccines/masking/social distancing are. He's also dispatched other trusted folks like Anthony Fauci to do the same. The President also delivered an address to the nation on COVID-19, on Sept. 9. He could do another, and we wouldn't be surprised to see that sometime later this month or early next month. However, a president can only go to that well so many times and, as with the mask mandates, such addresses largely end up being a case of preaching to the choir.

The executive summary is this: If Joe Biden were to get us on the phone tomorrow and ask "What more should I be doing?", we are not sure how we'd answer him. It seems he's pursuing all the avenues available to him, which makes sense, since he has a lot of very good public health experts working for him, since he is willing to listen to those experts (unlike some presidents), and since he really, really wants this pandemic to reach "permanently in the rear-view mirror" status.

M.M. in La Crosse, WI, asks: When are Trumpers and the Trumpettes ever going to face any consequences for their actions? These people have said and done some truly horrific things over the past few years and they are getting away with it.

I am sick and tired of hearing about all these different investigations or lawsuits. I just want results. These people are willing to tear apart our democracy and turn the United States of America into a fascist state. I am also scared to death about what is going to happen next November. To think that we have these whack jobs in key positions of our government is mind boggling.

Maybe the better question is: Will they ever face any consequences?V & Z answer: Like it or not, the wheels of justice turn slowly. That's partly due to an overburdened court system, but it's also very much due to the fact that the rights of everyone involved must be carefully observed. Not only is that the civilized thing to do, it limits the amount of time spent on appeals and retrials.

Not helping matters is that the American legal system is optimized when it comes to nailing the perpetrators of garden-variety crimes, particularly if those crimes are violent. It is especially efficient when the defendants are poor and cannot afford high-priced legal counsel. The system is vastly less efficitent when the crimes are more unusual, when they involve areas of the law that have not been spelled out very well, and when the defendants are politically powerful people with excellent legal representation.

Let's pause here to give a silly example. A few years back, (Z) was serving as executor of an estate, and ended up with legal responsibility for a property where the tenant had been living with a lease, but a lease where the rent was zero dollars (the tenant was related to the owner). And when the tenant refused to leave so that the house could be renovated and sold and the estate could be settled, it was necessary to get the court system involved. The lawyer that (Z) retained said that this situation, in the particular state in question (not California), was covered under the portion of the law that dealt with squatters. The judge who heard the case agreed. However, the local sheriff refused to enforce the order of expulsion, because in the sheriff's judgment, the tenant was a resident to be evicted and not a squatter to be expelled (there are different processes in each case). What was really going on here was that the sheriff was covering his rear end; he had done hundreds of evictions and knew exactly how to dot all the i's and cross all the t's, but he had done virtually no expulsions. So, (Z) was forced to go back to court and get an order of eviction so that the sheriff would do his job, even though all of the legal experts (lawyer, judge) involved in the case said it was not needed.

In any event, that was a relatively trivial encounter with an uncommonly invoked area of the law. Much of what Donald Trump and his followers did, by contrast, was hugely consequential, and involves areas of the law that have rarely or never been evoked. So, there is no way this is going to move quickly.

That said, we will guarantee you that some members of Team Trump will face consequences. We cannot say if those consequences will be civil or criminal, or how many Trumpers will get popped, or whether Trump himself will be among those who feel the pinch. But there are too many people who are too badly exposed for all of them to get off scot-free. Again, though, it's going to take time.

J.R. in Sarasota, FL, asks: There have been many stories in E-V.com documenting the lawsuits filed by and against Donald Trump. Has anyone ever attempted to calculate the cost to Trump of these multitudinous suits? He must have to pay lawyers, correct?

Are any of these court costs helpful in reducing his taxes?V & Z answer: There is almost certainly nobody on planet Earth, even Donald Trump's accountants, who could answer this question. The first problem is that he's really good at passing off his legal costs to... well, anyone who is not him. Just this week, it was reported that the RNC has increased its contribution to $1.6 million. He's surely getting his PACs to cover some costs, and his business his probably covering others. We wouldn't be surprised if he's also getting help from friendly billionaires, like Richard Uihlein. Since Uihlein is a private citizen, he doesn't have to disclose where his money is going, in contrast to the RNC.

An additional complication is that Trump often stiffs his lawyers, particularly if they lose. You would think they would demand retainers up front, and some do, but others are in it for the publicity or for the activism. For example, we doubt John Eastman has collected dollar one from the former president. Anyhow, some/many/all of his lawyers may know how much they plan to bill, and Trump and/or his accountants may or may not know exactly how much of those bills he intends to pay. However, there is nobody who has the full set of information right now.

As to the tax burden, you can generally deduct legal expenses if they were incurred due to your professional activities, but not those incurred due to your personal affairs (and we mean "affairs" in multiple senses of that word). Undoubtedly, Trump will claim that every lawsuit against him was filed because he was the president, and so they are all "professional" lawsuits. When he pays his lawyers whatever he's going to pay them out of his own pocket (probably not much, for the reasons outlined above), he'll make that claim to the IRS. Then it is up to the IRS to decide whether it accepts his story or not.

T.C. in Kittery, ME, asks: Thank heavens California Gavin Newsom is equipped with greater and more circumspective insight than the E-V.com guys. Newsom's idea "to draft a law allowing private citizens to file lawsuits for $10,000 against anyone who manufactures, distributes, or sells an assault weapon or ghost gun kit/parts in California" is a feasible approach. It might actually work. Although I think setting up a situation where abortion and gun rights duel against one another is not a wise idea.

Newsom's approach is a far, far better idea than E-V.com's idea: "What if a blue state passed a law that said that any citizen can sue a gun owner for $10,000 unless that gun owner can prove they are a member of a 'well-regulated militia'?" If you are aiming at a proliferation of: (1) gun clubs; (2) hunting buddies; and (3) your average, All-American well-armed, concerned citizen getting together and forming militias, that's the way to go about it. It would happen all over the country. You can be sure of it. That's also not a wise idea.V & Z answer: There's no actual question here, but you sent the message to our questions mailbox, so we're going to answer your "question" nonetheless.

In classrooms, it is very common to present situations that are simplistic and are impractical or impossible in reality, but are useful for making a point and/or teaching a lesson without adding needless complications. For example, anyone who's taken an introductory physics course has likely been asked to consider a perfect vacuum, even though such a thing is rare or nonexistent in reality (depending on which theoretician you consult).

Similarly, the examples we give in cases like this are not meant to be carefully thought out policy proposals. They are meant to be simple and clear hypotheticals.

G.W. in Oxnard, CA, asks: In "California Copies Texas," you wrote "Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) has directed his staff to work with the legislature and state AG to draft a law allowing private citizens to file lawsuits for $10,000 against anyone who manufactures, distributes, or sells an assault weapon or ghost gun kit/parts in California."

This idea seems to have a fatal flaw that there are legitimate customers for assault weapons. The U.S. military, allied military, and certain law enforcement agencies need these weapons. How could exceptions in such a law be crafted such that this Supreme Court would not find the law would place an undue burden on the legitimate uses of these weapons and thereby the law is unconstitutional?V & Z answer: As we note in the previous answer, our hypotheticals are not meant to be serious policy proposals. The same is true when a politician puts a trial balloon out there. Newsom's proposal might be a little closer to being serious than ours was, but he's still just spitballing at this point. Wait until the sausage is actually made before you evaluate how it tastes.

That said, there are plenty of laws on the books that specify that they only apply to private citizens. For example, here is the part of the California code that says that only private citizens can be compensated for serving on the Commission on Teacher Credentialing.

Politics

T.V. in Moorpark, CA, asks: Why don't the Democrats form a bipartisan committee to investigate the claimed 2020 election fraud? The Republicans will have to sit and watch every conspiracy nut job from Rudy Giuliani to the MyPillow Guy spew their nonsense.

If the Republicans refuse to participate, then the Democrats have a great talking point in that the Republicans are obviously afraid of exposing the truth about the election.V & Z answer: "Tonight on Hannity: Democrats concede that election-fraud claims are serious enough to warrant a full congressional investigation."

The folks in the Fox bubble (and the associated bubbles) have been taught over the last decade, particularly by Benghazi and Hillary's e-mail server, that "Congressional investigation" means "legitimate." Unless they don't agree with the investigation, of course—in that case it's a witch hunt and fake news.

The Democrats don't need to grant any further legitimacy to election fraud claims or, for that matter, to the use of congressional investigations for purposes of political grandstanding. And they certainly don't need to give more oxygen or more air time to Rudy Giuliani, Mike Lindell, or any other members of that cadre. Those who are inclined to find those men ridiculous have already made up their minds.

A.C. in Columbus, OH, asks: After reading your piece on Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) and his daughter, it got me thinking about how much things have changed in the past 100 years. Specifically, I'm referring to what was considered the political scandal in American history prior to Watergate: Teapot Dome. The brief rundown of that scandal is that President Warren Harding transferred control of some oil fields from the Navy to the Department of Interior, and then Interior Secretary Albert Fall sold those leases without competitive bidding to oil companies after taking bribes from those companies. How is that all different from what is happening today, except for "bribes" are now called by the much more palatable name of "donations"?

Manchin's daughter is "donating" (actually, bribing) to her father, and he just so happens to oppose allowing the government to negotiate drug prices, which in turn could hurt her business. How is this legal? More to the point, how can such an action go from being what was seen for nearly 50 years as the defining scandal of political corruption, to now being not only commonplace, but expected? Is it all because of Citizens United, or have other laws changed in the last 100 years which basically said "Hey, some corruption is ok!"? You say influence peddling is a crime, but let's be honest, isn't that what lobbying, Super PACs, and $5,000 a plate dinners are all about?V & Z answer: Members of Congress, and in particular members of the House, have been taking money from outside interests for a very long time. And in some periods of U.S. history, most obviously the Gilded Age, it was far, far worse than it is now. There were lots of late-19th century politicians who were shaking down both private interests and members of their own party.

It is true that today's politicians have gotten pretty good at blurring the line between "bribe" and "legitimate campaign contribution," and insulating themselves from legal and political blowback. They have accomplished this, in part, through the use of PACs and campaign committees, and they have accomplished it, in part, by waiting until they are out of office to actually begin lining their own pockets (often with cushy corporate-board gigs or other sinecures). In Manchin's case, it probably also helps that his daughter has a different last name than he does.

All of this said, we would argue that the comparison between Manchin and Teapot Dome doesn't really stand up very well. First of all, Teapot Dome involved some of the shadiest and most unpopular oil barons of that era, like Edward Doheny. Second, there is no blurry line between "bribe" and "legitimate campaign contribution" for a cabinet secretary, since they don't have to run for reelection. So, it was very clear that Albert Fall was profiting personally from the money he got.

The crude modern equivalent to Teapot Dome would be if, say, Elon Musk wrote a $500,000 check to Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland in exchange for being allowed to build a Tesla factory in Golden Gate Park. That would surely trigger a massive scandal when it came to light.

D.G. in Bradenton, FL, asks: We all remember the Merrick Garland tragedy in 2016, when the Senate Republicans, led by Mitch McConnell, prevented his nomination from even being considered by the Senate.

My question is a "what if?" How might Garland, if he had been confirmed, have voted on the cases that came before the court? I ask this question because many liberals fervently wanted him on the Court, which would have given the liberals a 5-4 majority.

Garland, however, is now the Attorney General, but has come under criticism from liberals because he is not been forceful enough in undoing the damage to the Department of Justice under the Trump administration

Which brings me to my main point: It appears that Merrick Garland is not the liberal white knight that many had hoped for when he was nominated to the Supreme Court. How do you think Garland would have voted on the many important cases that have come before the court? Might he have been more of a centrist, along with Chief Justice John Roberts?V & Z answer: Barack Obama chose Garland with the idea that he would be centrist/experienced enough for Republican tastes, and that McConnell & Co. would rather swallow that bitter pill as compared to a much bitterer pill in the form of a fire-breathing leftist nominated by President Hillary Clinton. Obama did not anticipate that Senate Republicans would roll the dice, nor that their gamble would pay off when Donald Trump won the election.

That said, Obama is the most cautious and methodical president in modern American history. Merrick Garland had a vast amount of jurisprudence under his belt when he was nominated, and you can be absolutely certain that it was left-leaning and that Obama made sure that was the case. Garland might have sided with the conservatives on occasion, but that happens with all of the liberal justices. And on the biggies, like abortion, you can be confident he would have voted with the liberal bloc.

J.W. in Aston, PA, asks: You frequently quote opinion polls—approval ratings for the president, supreme court, etc. and write as though those polls should be used as a guide or measuring stick for making decisions, statements, or whatever purpose they serve. This week, in a commentary on packing the court, you state, "Poll after poll has shown that, in recent years and months, confidence in the judicial branch is at all-time low levels," citing a link to Gallup. How can you be so sure? At the same time, in recent years, voter polls have been quite a ways off, and you have frequently commented on why polls have been inaccurate.

How do opinion polls measure up to election polls (or vice versa)? How many grains or buckets of salt are needed to either accept or dismiss approval ratings and what's the difference?V & Z answer: First of all, we refer to polls of various sorts because it's the best data we have. And even imperfect data is better than no data.

Second, don't go too far in overstating how inaccurate polls have been recently. Yes, there have been some high-profile misses, particularly on some of the 2020 Senate races (ahem, Sara Gideon). But most polls have actually been on target or, at very least, within the margin of error, including most of the 2020 presidential polls and the 2021 Georgia special election polls.

Third, approval polls are generally more accurate than voter polls. The latter have more moving parts; not only does a pollster have to make an educated guess as to what the electorate will look like on Election Day, they also have to figure out how likely a particular respondent is to actually show up and vote, and how certain they are about their stated choice. With an approval poll, the pollster may not even have to worry about what "the electorate" looks like. If they're just gauging public opinion, well, they know full well what percentage of Americans are Black female senior citizens who live in Colorado. They don't have to make a guess as to how many Black female senior-citizen Coloradans are going to vote this year. And even if the pollster does consider demographics in an approval poll (e.g. "Here is Joe Biden's approval among likely 2024 voters"), they still don't have to worry about how likely the person is to take action. They're just evaluating the person's opinion of Biden, and not whether they will actually get themselves to the polls to vote for/against him.

Fourth, and finally, approval polls function as de facto tracking polls. That is to say, if Gallup has Biden's approval at 40% today, that might or might not be on target. But if they had him at 50% a month ago, then clearly something has changed for the worse for him, regardless of whether or not the numbers are exactly correct.

And so, when the Supreme Court begins to pull the worst confidence numbers it's gotten since the advent of political polling, there's something real there. Especially since there's an obvious explanation for those poor ratings.

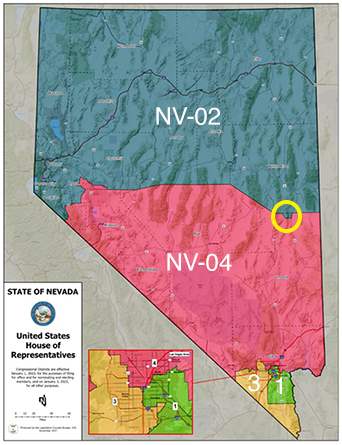

R.E.M. in Brooklyn, NY, asks: This week, (V) addressed the new congressional district map the Democrats of Nevada (who hold the trifecta) adopted, noting that Rep. Dina Titus (D-NV) would not welcome the Republicans that were added to her district in order to make the two other Democratic-held districts bluer. On Thursday, Titus voiced her displeasure vehemently and profanely. What does the new map do to her previously D+25 district? Were so many Republicans moved there that Titus is now really in danger of losing her seat?

V & Z answer: Yes, she is in danger, as her new district is now D+4. You can see why she might be miffed. But the fact is that nearly all of the Democrats in Nevada are in the city of Las Vegas. And if you make Vegas into a district, it ends up really blue, but then the surrounding districts end up purplish-red. Whereas if you crack Vegas, then you can make three reasonably safe Democratic districts.

And so, under the old map, Titus was completely safe, whereas Steven Horsford (D) was holding on in an R+1 district and Susie Lee (D) was holding on for dear life in an R+5 district. Now, Horsford's district is D+5, Titus' is D+4, as noted, and Lee's is D+2. The new setup is at least a little more red-wave resistant than the old one, and while Titus might be angry, she certainly shouldn't be surprised. The Democratic Party just can't afford that many wasted Democratic votes in a purple state.

R.T. in Arlington, TX, asks: After seeing the Nevada map on Wednesday, my curiosity got the better of me. Do you folks (a term that is both quaint and gender-inclusive) have an idea about the little notch I've circled below?

I searched on Google Earth and found no signs of a town or population center worth putting into NV-02. Now my imagination is swirling about a large branch of the Cartwright family that has built a new Ponderosa in an underground bunker.

V & Z answer: If it's the Cartwrights, then they are on the move, because the Ponderosa was located on the opposite side of the state (outside of Reno).

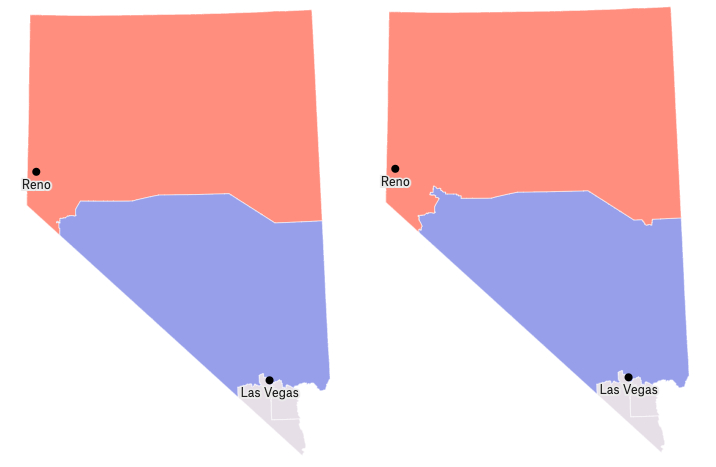

In any event, we can discover nothing, either in terms of comments from map drawers, or from Google Earth, that explains this. However, here are the first (left) and second (right) maps proposed by the Democrats this cycle:

That the notch does not exist in the first proposal suggests there is nothing special about that part of the state that made it a priority to get it into a particular district. Meanwhile, that plus the small arm in the west that exists only on the second map suggests to us that the second map is just a little more refined and a bit more precise so as to make the populations between the two districts equal. Since the arm stretches into the Reno suburbs, we would guess that it was meant to pick up a little population for NV-04 and that the notch in question was meant to give a smaller amount back to NV-02.

That said, this is just our guess, and if there is a reader who knows better, we are happy to be corrected.

Civics

S.P. in Harrisburg, PA, asks: There has been talk of Donald Trump running again in 2024, and the a likely VP candidate would be Ron DeSantis of Florida. With Donald Trump now being a Florida resident, they would both be from Florida. Is there a restriction on both members of the presidential ticket being from the same state?

V & Z answer: This is something that people, including members of the media, often get wrong. There is no prohibition against candidates being from the same state. There is a limitation on electors, however. Specifically, Article II of the Constitution states: "The electors shall meet in their respective states, and vote by ballot for two persons, of whom one at least shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves." That restriction is affirmed in the Twelfth Amendment, which states: "The Electors shall meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves." So, if a Trump/DeSantis ticket won Florida, and neither of them had changed home states, then the 30 electors that Florida will have in 2024 could not vote for both Trump and DeSantis.

Presumably, if this were to come to pass, then Trump would get the electors and DeSantis would not. And if the Trump/DeSantis won a very close election in the Electoral College, then nobody would be elected VP and it would be up to the Senate to pick from one of the two top electoral vote getters. At that point, things might get a little hairy, depending on how willing the Democrats would be to play hardball. To make a decision, at least two-thirds of the senators have to be present for a quorum, and then it takes a majority vote. If the blue team wanted to stick Trump with a Democratic VP, they could refuse to appear in the Senate chamber until the Republicans surrendered. That said, the Democrats don't generally have the stomach for such things.

All of this said, we do not believe a Trump/DeSantis ticket is feasible. That's one ultra-alpha male too many.

J.H. in Boston, MA, asks: You wrote that Donald Trump, if chosen as Speaker of the House next year, would have all the same powers as current speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), except the power to vote on bills. While Pelosi does have that power, does she normally exercise it? I seem to recall hearing somewhere that the speaker does not normally vote on bills, unless there's a tiebreaker, which is surely quite rare, since the Speaker also has the discretion to decide which bills come to a vote, and not bring any which they don't already know have the votes to pass. In other words, while that may be a difference in power on paper with a non-representative speaker, in actual practice their powers would be identical. Is that not correct?

V & Z answer: It's basically correct.

There was a time when the Speaker of the House was forbidden from voting on any bill, though that ended more than 150 years ago. Now, it is at their discretion. Pelosi votes in the case of ties and, more commonly, in the case of bills where there may not be a tie, but she wants to signal her support (for example, she voted for the John Lewis Voting Rights Act). It would be very rare for a non-voting Speaker to actually matter in terms of passing or not passing legislation.

T.R. in Emmaus, PA, asks: This is a bit off topic from a lot of the current news, but I noticed one of the banners at the top of your page is for the Rural Utah project. Having lived in Utah at one time, I was curious and clicked. They appear to have specific interest in turning out Native American voters. It got me thinking about some of the voting laws in Western states with significant native populations. A lot of those laws seemed designed to make it more difficult for those living on reservations to vote—requiring difficult-to-obtain IDs, requiring a physical mailing address, etc. Since reservations are administered by the Interior Department, could the Biden administration take some action to address these obstacles with executive action or new interpretation of existing law? I know the former guy was not interested in these issues, but despite his protests, he's no longer in charge.

V & Z answer: Since elections are not administered by the federal government, there is not a lot that Biden can do via executive order. However, Congress is certainly empowered to take steps to improve Native Americans' access to the ballot. And indeed, one of the sections of the aforementioned John Lewis Voting Rights Act is the Native American Voting Rights Act of 2021. It includes many provisions that would address issues specific to Native American voters, including:

- Requiring that every tribal reservation have at least one polling place and one voter registration site

- Pre-paid absentee ballot envelopes

- Decreeing tribe-issued ID to be valid for purposes of satisfying voter ID laws

- Language assistance in Native languages

- Pre-clearance for any changes to voting laws that would affect Native Americans

- Allowing tribal members without an address to use a building belonging to the tribe as their "home" address

S.S. in Atlanta, GA, asks: What is the actual statute behind the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court being able to decide who writes the opinions for a case? Is there something legally binding or is this just another one of those traditions?

V & Z answer: Note that it's not actually the Chief Justice who decides; it's the most senior justice on the majority side.

In any case, most of the privileges and powers of the Chief Justice are rooted more in tradition and informal agreements than in statute. The Constitution acknowledges the existence of that office, but only long enough to say that the Chief presides in presidential impeachments. Meanwhile, the Judiciary Act of 1798 says this:

Be it enacted, That the supreme court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices, any four of whom shall be a quorum, and shall hold annually at the seat of government two sessions, the one commencing the first Monday of February, and the other the first Monday of August. That the associate justices shall have precedence according to the date of their commissions, or when the commissions of two or more of them bear the same date on the same day, according to their respective ages.This makes clear that not all justices are created equal, and that there is precedence based on seniority.

There is nothing in the law, however, that actually states who gets to pick the chief justice. By custom, it's the president, but it would be equally legal for the justices to choose among themselves. In fact, the law excerpted above could be read as implying that the longest-serving justice is the chief. And as you might imagine, if the choice of who is chief justice isn't spelled out in any particular law or clause of the Constitution, then the specific prerogatives of the chief justice aren't spelled out, either.

E.W. in Belton, TX, asks: How did the framers of the Constitution and other key leaders in the early days of the U.S. expect debates over constutionality of an issue to be resolved before Marbury v. Madison (1803)? Was there any surprise that John Marshall claimed the right of judicial review for the Supreme Court or was that sort of an assumed thing that was bound to happen? I seem to remember reading that Thomas Jefferson expressed concern over the constitutionality of the Louisiana Purchase, and the Federalist Papers seem to assume the need to interpret the Constitution. But, perhaps the framers and other leaders understood these issues of constitutionality from a perspective I'm not thinking of?

V & Z answer: They expected the courts to resolve debates over the constitutionality of whatever the issue was. They also expected the courts to engage in interpretation of other laws, like "Do Native Americans count for purposes of the population quotas in the Northwest Ordinance?" or "Who, if anyone, owns enslaved people who were being smuggled illegally?"

Marbury v. Madison did not give the courts (and, in particular, the Supreme Court) the power to interpret laws, it gave the power to completely invalidate laws that were deemed unconstitutional. In other words, the founders expected that the Court would answer questions like "Can Madison be forced to give Marbury his commission or not?" They did not expected that the Court would decide that the law granting it authority over Madison was unconstitutional, was therefore stricken permanently from the books, and that, consequently, while they thought Marbury was entitled to his commission, they had no actual say in the matter.

F.H. in Pacific Grove, CA, asks: I never thought I would find myself quoting Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ), but when she said the filibuster serves to "protect the country from repeated radical reversals in federal policy", it directly addressed the question that's been bothering me for about a year: If the filibuster is eliminated and the Senate (and the house and the presidency) doesn't include a majority of reasonable, law- and principle-abiding people, what's to prevent the Republicans from reversing any new voting rights legislation with new national legislation even more restrictive than what's in place now?

My guess is that the answer is "nothing," but it's better to have real voting rights for two (or possibly more) years than nothing at all. I'm still so depressed.V & Z answer: It is true that, if the filibuster was eliminated, it would be easier for a Republican majority to ram bills through the Senate, potentially including anti-voting-rights bills.

However, a big part of what has made the current Republican strategy work is that it's death by a thousand cuts when it comes to voting rights. It is tough to channel voters' outrage when we're talking about 200 state-level bills that restrict voting rights in various ways. That deluge is also tougher to fight in court because it's battle after battle after battle across many different levels of the court system.

By contrast, if a Republican Congress were to pass the Anti Voting Rights Act of 2023, that would give Democrats a single rallying point to motivate voters, and would give a single point of focus to the legal struggle. This would not work to the advantage of the Republicans, which is why they haven't made a serious effort to pass national legislation of this sort, even when they had the trifecta.

J.L. in Baltimore, MD, asks: Is there any other country that has a system like the filibuster, where a minority in the legislature can defeat a bill? Or does every other legislature require a simple majority?

V & Z answer: The classic filibuster, where a member talks until they are blue in the face so as to run out the clock on a legislative session, is literally thousands of years old. Cato the Younger, who died in 46 B.C., was famous for it. And there are many modern nations whose legislatures tolerate some version of the talking filibuster, including the U.K., Canada, Ireland, and the Philippines. However, we are not aware of any body beyond the U.S. Senate that allows a member to table a bill by merely raising their hand and saying "filibustered!"

History

R.S. in San Mateo, CA, asks: You wrote: "Gerrymandering works fine for the House, but not at all for the Senate."

That got me wondering... what has been the largest party imbalance between the two bodies of Congress? Currently, it's in balance with Democrats having 50.8% of the House and 50% of the Senate. With a split government, how wide has the chasm been?V & Z answer: Well, keep in mind that there was a brief period two centuries ago when there was really only one political party. And so, the 16th Congress (1819-21), for example, had a Senate that was 82.6% and a House that was 85.2% Democratic-Republican. For the 17th Congress (1821-23), those numbers were 91.5% and 83.2%, respectively.

Since the 1830s, the country has consistently had two major parties. And the most imbalanced Congress in those 190 years or so is the 74th Congress (1935-37), where the Senate and the House were 75.0% and 73.7% Democratic, respectively.

S.B., Los Angeles, CA, asks: It has been reported that Mark Meadows being held in contempt of Congress is the first time this has happened since 1830-something. Would you please sober up and/or wake up the staff historian to give us the lowest down on that previous contempt?

V & Z answer: It's the staff mathematician who is a drunk, not the staff historian. Please try to keep up.

The last current or former Representative to have been held in contempt of Congress is actually quite famous. It's Sam Houston, who had represented Tennessee in the House until 1827, and who in 1832 was accused of corruption by Rep. William Stanbery (Jacksonian-OH). Houston responded by beating the tar out of Stanbery with a cane. That sort of thing sometimes happened in the antebellum era. Anyhow, Houston was found in contempt, formally censured, and ordered to pay a fine of $500 (about $13,000 today).

M.C. in Santa Clara, CA, asks: M.G. in Boulder asked about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In your answer, you did not discuss the "most reasonable" way to have persuaded the Japanese to surrender: Send an urgent message to Japan to assemble the High Command to observe the vaporization of some Japanese island (with Little Boy). Then, after the mushroom cloud had settled, tell the Japanese: "We have 100 more where this came from (bluffing), and we will reduce your country to rubble unless you surrender now." If they did not surrender in, say 3 days, then fine: Drop Fat Man on a city, killing thousands of women and children and other non-combatants in the most horrific war crime in modern history.

But they didn't do that.

Was Harry not good with his Poker Face?

P.S.: I have difficulty calling myself an "American" when I know my country has been responsible for war crimes and atrocities like this. And I simply don't believe "we saved lives." It's American Propaganda, and to have you support that propaganda saddens me. None of us was there, granted. But it would be difficult to label Truman's actions as anything but horrifically barbaric and illegal. And people worry about mustard gas. Gag me.V & Z answer: As Truman was considering his options, he received two very carefully worded letters from scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project. One of them, headlined by Leo Szilard and signed by several dozen junior scientists, urged Truman not to use the atomic bombs unless absolutely necessary, and only after giving the Japanese every opportunity to surrender. The second, which was signed by the three rock stars of the Manhattan Project (J. Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, and Ernest Lawrence) told the President that, as regrettable as it might be, there was no real option except to use the bomb.

The second letter includes this passage:

The opinions of our scientific colleagues on the initial use of these weapons are not unanimous; they range from the proposal of a purely technical demonstration to that of the military application best designed to induce surrender. Those who advocate a purely technical demonstration would wish to outlaw the use of atomic weapons, and have feared that if we use the weapons now our position in future negotiations will be prejudiced. Others emphasize the opportunity of saving American lives by immediate military use, and believe that such use will improve the international prospects, in that they are more concerned with the prevention of war than with the elimination of this specific weapon. We find ourselves closer to these latter views; we can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.There are two takeaways here. The first is that a "technical demonstration" was absolutely under consideration, but some of the most expert people in the country were unpersuaded that it would work. Oppenheimer, et al., don't go into detail as to their thinking, but their concerns were: (1) The Japanese would not be suitably impressed, (2) the U.S. had a limited number of bombs available, due to inefficiencies in purifying the radioactive isotopes, and couldn't afford to waste one, and (3) the demonstration might be counterproductive if the bomb failed to explode. It is worth noting that you propose giving the Japanese government 3 days after this hypothetical demonstration before deploying the bomb against human targets. However, there were 3 days between Hiroshima (Aug. 6) and Nagasaki (Aug. 9), and the Japanese government did not surrender in that time. And that, in turn, gives some credence to the supposition from Oppenheimer, et al. that a technical demonstration was not enough.

The second takeaway is that the scientists—who again, were not happy to make this recommendation—were not just thinking about ending World War II, but also about the future of warfare. They were persuaded that a full demonstration of the bomb's destructive potential would cause nations to think twice, in the future, about using nukes or about launching world wars. And it certainly appears they guessed right. Since 1945, there have been no world wars and there have been no nuclear bombs deployed.

This is not to defend Truman, Oppenheimer, or anyone else. What we are defending here—and it is the historian (Z) who is writing this, of course—is the ethics and the methods of the historical profession. The goal, as much as is possible, is to understand, and not to cast aspersions based on modern values and on hindsight. In 1945, Truman was sitting at his desk in the Oval Office, knowing full well that the buck stopped with him. He had to think about ending World War II. He had to think about the future nuclear arms race that he knew was coming. He had to think about the Russians, and trying to secure the upper hand in that sure-to-be-difficult rivalry. He also knew that war is an ugly thing, that bombing of civilians was commonplace in World War II, and that the Japanese had killed plenty of civilians (particularly Chinese and Filipino citizens) in brutal ways.

At the same time, Truman was very well aware of the counter-arguments. There were the scientists, led by Szilard, who told him not to do it. There were both civilians and military men pushing for an alternative approach, whether that was a technical demonstration or continued use of conventional bombs. He also knew how brutal the weapon was. In his diary, for July 25, 1945, the President wrote: "We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world. It may be the fire destruction prophesied in the Euphrates Valley Era, after Noah and his fabulous Ark."

And that leads us to this conclusion: We do not feel Truman was right, nor do we feel he was wrong. He clearly had plenty of justification for the decision he made, and he clearly had plenty of justification for a different decision, if that was his choice. And we are very glad we didn't have to make the call, because the arguments on both sides are so strong.

One more thing. We are sometimes reluctant to get into touchy issues, whether the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or genocide, or slavery, or whatever because that inevitably produces a bunch of e-mails attacking us as propagandists, apologists, colonialists, racists, neo-Confederates, antisemites, etc. Being attacked like that—and we've gotten all of those—is a little bit of a downer, but we can handle it. The real downer is that we're clearly not reaching anyone who resorts to these sorts of attacks, either because we did a poor job of communicating or because they are too fully set in their views. Either way, as teachers, that's the real downer.

Gallimaufry

J.K. in Las Vegas, NV, asks: I have both a question and a comment. The question first: I often click the headlines in the TG section in E-V.com, but I have never paid for a news analysis site to date and I don't see that changing, but I'm curious; do you two pay for any news analysis sites? Are you subscribers to Taegan Goddard's site? If you were going to suggest one news source to pay for, which would it be?

As for the comment, I personally liked the old format better where the two of you wrote an analysis 7 days a week. When you started the question page on Saturdays I liked it well enough because there were usually good questions that I had myself that others asked, or else someone thought to ask a questions that I hadn't even considered. The Sunday mailbag, however, is a letdown for me. I rarely read the comments unless I see that you two have replied, then if your reply sounds interesting I will read that comment. Otherwise, I skim the Sunday posting. Have other readers expressed their preferences re: the Saturday and Sunday pages?V & Z answer: We both have subscriptions to the two newspapers that cover politics best, namely The New York Times and The Washington Post, but not much beyond that. If you were going to spend your money on only one site, it should probably be one of those, with a slight bias towards the Post If you want a politics-only site, then we would suggest Talking Points Memo or Heather Cox Richardson's Letters from an American. Those are both pretty good complements to our site, in various ways.

As to Saturday and Sunday, we've gotten plenty of letters from people who say that one of them, or the other, is their favorite day of the week. We also get hundreds of questions and hundreds of letters each week, which is a different sort of affirmative vote. In any event, going back to the old model is not especially likely. First of all, we need a change of pace sometimes. Second, there really isn't enough fresh news over the weekend.

T.J.R. in Metuchen, NJ, asks: I really don't understand the choice of Elon Musk as Time's Person of the Year. I honestly believe the best choice (and I have major problems with him) was Joe Manchin. Maybe Officer Eugene Goodman. I understand Time is (I hope?) trying to be objective but come on. Is Elon trying to buy Time Warner? Are they tweaking Jeff Bezos? Help me out here.

V & Z answer: We will start by observing that the Person of the Year is supposed to be of global significance, and representative, ideally, of one or more of the larger storylines of the year. And in the editorial staff's explanation of their choice, they make very clear what larger storylines they think Musk embodies:

Musk's rise coincides with broader trends of which he and his fellow technology magnates are part cause and part effect: the continuing decline of traditional institutions in favor of individuals; government dysfunction that has delivered more power and responsibility to business; and chasms of wealth and opportunity. In an earlier era, ambitions on the scale of interplanetary travel were the ultimate collective undertaking, around which Presidents rallied nations.

Today they are increasingly the province of private companies. To Musk, that is progress, steering capital allocation away from the government to those who will be good stewards of it. To others, it is testament to capitalism's failings as staggeringly wealthy, mostly white men play by their own rules while much of society gets left behind.It's a fine argument, as far as it goes, though it's strange to us that Time did not choose, either this year or last, someone connected to COVID-19 (though they did name scientist Katalin Karikó as "Hero of the Year" for 2021, so they must have regarded that as covering their bases, pandemic-wise).

We would also point out one more thing: The dominant motivation here isn't objectivity, it's selling magazines. This is Time's swimsuit issue. And if they're considering two candidates, one of whom is famous and provocative, and one of whom is not, they are almost always going to go with the famous and provocative person. If that triggers a bunch of "What was Time thinking?" articles by other outlets, as it did this year, all the better.

B.B. in St. Louis, MO, asks: Could anyone designated "Christian" at birth explain the following for me: Which is more important for the faithful, belief in the divinity of Jesus or following the teachings of Jesus?

V & Z answer: We are not the people to answer this, but we have readers who majored in divinity studies or similar fields, and additional readers who are devout adherents of one branch or another of Christianity. So, if those folks care to weigh in, we'll run some of those responses.

Previous | Next

Back to the main page